Muti Magic at Carnegie Hall

Chicago Symphony Precise, Passionate, Compelling

By: Susan Hall - Oct 07, 2012

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Riccardo Muti, Music Director and Conductor

Richard Wagner, Overture to the Flying Dutchman

Mason Bates, Alternative Energy

Cesar Frank, Symphony in D Minor

Carnegie Hall

October 4, 2012

Riccardo Muti and his Chicago Symphony Orchestra opened the Carnegie Hall Season. And what a splendid welcome. If you missed the opening night concert, its richness and excitement are streaming live on the Carnegie Hall Site all week.

Featured was Carl Orff's Carmina Burana. When Muti conducted it in 1980, the composer declared the performance a "second premier." Orff went home and made changes which he autographed and then sent to Muti. Such is Muti’s gift.

The Flying Dutchman overture opened the next program, filling the hall with color and sound. Wagner had written his opera in two months; the overture, which contains all the leitmotivs, last. All the color and sounds of the sea’s howling winds and storms were captured. Wagner had manned the walls in Dresden with Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin who would write about Flying Dutchman, “That was water."

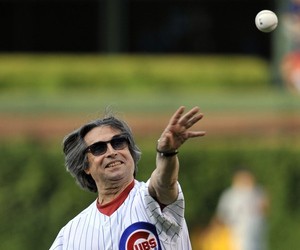

The music imagines the spectral Dutchman’s boat, tall sails manoeuvering through fjords. But as always with Maestro Muti, conducting is about the present ear and the eye. Immediately you see that his body is an instrument as much as any of the instruments in the orchestra, drawing forth stark, fierce chords in the woodwinds as the strings plunge into the middle of the raging storm.

Next up was the New York premier of Alternate Energy by the Oakland phenom Mason Bates, one of two composers in residence in Chicago. In the Bates we had ‘ice’ and water. The finale, Cesar Frank, would all but drown us in its delectable texture.

Composer Bates tagged Muti as a musician able to achieve the drama of music each time he lifted or swept down his arm. Bates has said, “The electronics work within the orchestra like a section…it’s music for an orchestra with a new element.”

Bates formed an alliance with the conductor. Muti has remarked that contemporary music often has tremendous rhythmic complexity “that you have to pull from the orchestra without the slightest slip, or risk the piece falling apart.”

Onstage creating percussion on the computer, Bates performed his fascinating Mass Transmission as part of the American Mavericks program last spring. At Carnegie for Alternate Energy the computer was at the back of the orchestra, but its sounds came from the stage. A big percussion battery and recorded location sounds mixed with the orchestra's instruments. Whushes like air going out of a tire, or something more gross, drew chuckles from the audience. Even cutting edge sounds delivered via computer can be old-fashioned fun.

Bates says, “The players (in the orchestra) almost always see that I love live orchestra and have worked for a long time to try and understand this beast….The thing that’s most reassuring is, after a concert, to hear from the players and conductor that it all worked together. “

Alternate Energy takes place over four centuries. The model T Ford chugs along after the clopping of farm horses. The 20th century goes inside to the sounds of the Fermi lab cyclotron outside of Chicago. The sounds of an eerie wasteland in a present day Chinese province flow into the end of the world in Iceland.

Bates may have used a Clinton manual to augment the percussion battery with car parts he found in a junkyard. Billowing waves of John Adams’ like sounds, jazz, hip-hop and Stravinsky. Rising and falling waves of soft strings. A nuclear facility approaching meltdown.

Bates’ ultra modern sounds are combined also with the swelling melodies and orchestration of composers like Ferde Grofe and Aaron Copeland. The horse clops could have been lifted from the Grand Canyon Suite. Or this clopping could just be a naturally occurring click track. Bates’ day job in composing. At night he is a DJ who knows how to continue the most interesting kernels of music and leave the clichés behind.

Muti signals his troops to listen to one another. He writes that he “makes himself available through long, lonely hours of study, listening and thought.” But the sheer joy he transmits masks the work, but not his passion. The last movement is like a Respighi future in Pines of Rome. Principal percussionist Cynthia Yeh and concertmaster Robert Chen threw themselves into the music with Bates and Muti.

This music is accessible. As Muti and the CSO perform, the audience is pulled along almost effortlessly

Muti is going to meet a young audience half-way. Bates offers this opportunity. Instead of jamming a radically new offering sandwiched between two old fashioned pieces, he offers a bridge. Of course if young people come to a Muti concert, they are going to fall in love with a composer no matter what his dates. Among newcomers, young Andris Nelsons conducting in Birmingham stands out for his Muti-like musical intelligence and passion. That’s what an audience wants. Maestros committed to music as the most important thing in life.

Like Wagner’s wish for continuity, Muti’s program intentionally links one piece to another. Irresistible as he dances, Muti offers himself up in the service of music.

A three-note theme lifted from Beethoven’s Last Quartets echoes throughout the Cesar Frank Symphony. The theme asks “Must I then?” The answer at Carnegie is Yes, we must. For our pleasure.