Barbara Takenaga at Williams College Museum of Art

The Optics of Metaphysical Cosmology

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 07, 2017

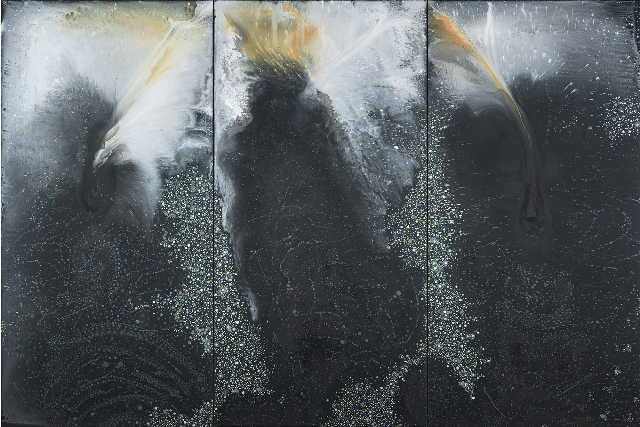

The Williams College Museum of Art, through the end of January, is presenting “Barbara Takenaga” a stunning overview of 60 works of varying scale, that represent two decades of her oeuvre. The selection was made in collaboration with independent curator Debra Bricker Balken.

Entering a large gallery and a smaller adjoining one the viewer is overwhelmed with the rich, complex density of the paintings. It makes me recall viewing the Book of Kells at Trinity College in Dublin. There is that same labor intensive astonishingly minute detail but here greatly enlarged in scale.

For the Carolingian monks living a life of austerity it was meditative labor intended as service to God. One ponders the motivation of the artist creating this similarly demanding and laborious but secular work.

Critics have commented on how her work expands our baseline of patterned forms of abstraction. In formalist, post modern discussion it is anathema to ask what it is about or probe the motivation of the artist.

As a reactionary observer there is an urge to know the how and why of such a compulsion. The demands of studio time for such work would seem to preclude and encroach upon the down time of the artist. At the end of the day one might imagine being utterly drained but richly satisfied.

In the early decades of the 20th century the seminal artist, Marcel Duchamp, then best known for “Nude Descending a Staircase” a cause célèbre of the 1913 Armory Show, abandoned painting. Having demonstrated his mastery of the brush he declared it “too retinal.”

Under his pervasive influence we have admired the cleverness and invention of generations of conceptual ideas. The response is often “why didn’t I think of that?”

The corollary has been an elitist contempt for the hand made. There is the familiar quip and put down that Salvador Dali was the greatest artist of his generation “from the wrist down.”

The challenge of post modernists viewing this work is that it goes beyond a clever idea. There is the sense of not being able to do this. In a very outrageous manner it trumps conceptualism.

From Duchamp on there have been regular pronouncements of the death of painting. Just as routinely there are the equivalences of painting is dead long live painting. In that trope Takenaga is the latest and most vivid incarnation of the primacy of the hand made.

She was born in North Platte, Nebraska in 1949. Takenaga has been the Mary A. & William Wirt Warren Professor of Art since 1985. A couple of years ago she created a mural along the long wall of a corridor of MASS MoCA next to its Hunter Center performance space.

The Williams exhibition invites tracking the aesthetic development of the artist. For individuals working in this manner that proves to be an incremental process. Artists more focused on concepts than technique are capable of dramatic changes. For Takenaga the progressions are more minute requiring intensive viewing and critical analysis.

For an art historian or modernist there are signifiers of ideas and resources. One may start from early abstract art with the terroir of Kandinsky and the Bauhaus. What is the substrate that the paintings are rooted into?

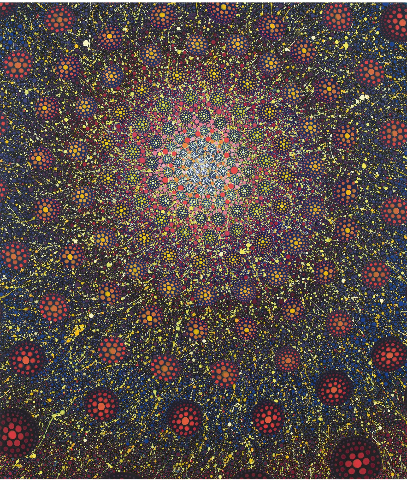

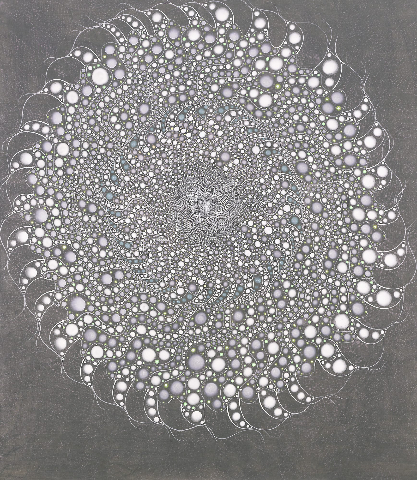

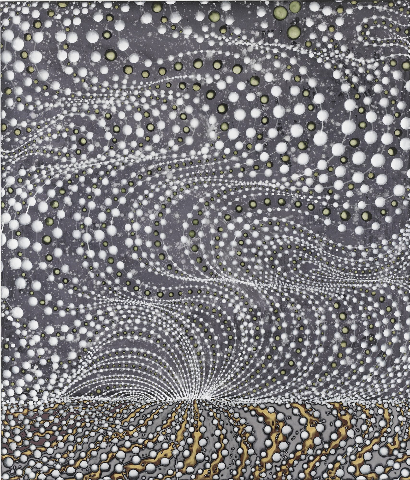

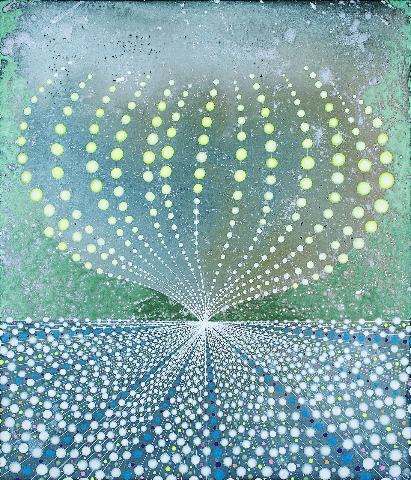

The room of smaller early works reveal direct lines to the op art of the 1960s and iterations of psychedelic art which absorbed that as well as aspects of Tantric mandalas.

There is a visual but not psychic connection. Op art was a popular tag applied to works in the seminal 1965 MoMA exhibition The Responsive Eye. A commonality was the visual jump and after patterning of moiré designs. The responsive eye becomes confused and unable to scramble and focus on such complex abstractions.

For a time op entered the mainstream of popular culture with design and fashion. It ran neck and neck with pop but soon faded. Artists like Bridget Riley, Ben Cunningham, Agam, Julian Stanczak, Guido Molinari, Claude Tousignant, Richard Anuszkiewicz and Victor Vasareley have become asterisks of the 1960s.

The motivation of psychedelic art was a visual expression of LSD induced hallucinations. After an acid trip it was usual for mandala-like, retinal flashes to remain for hours, days and in some cases one could see for miles and miles and miles.

Viewing the paintings of Takanaga is quite different from that. More closely, perhaps, it evokes the circles of Kusama.

The paintings, other than the early ones, don’t have that familiar visual jump and jive. While richly patterned they prove to be curiously flat on the retina. It is impossible to say whether this is in the eye of the beholder or intentionality of the artist.

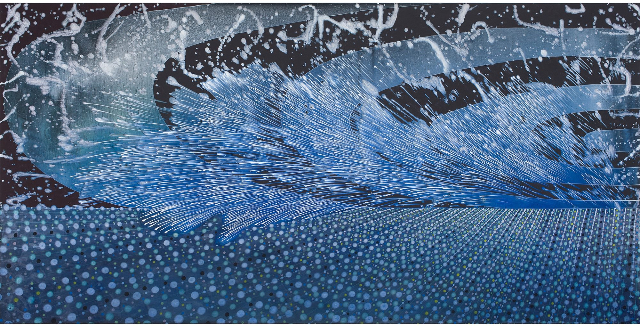

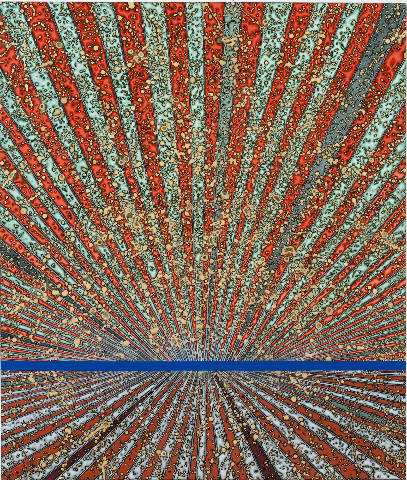

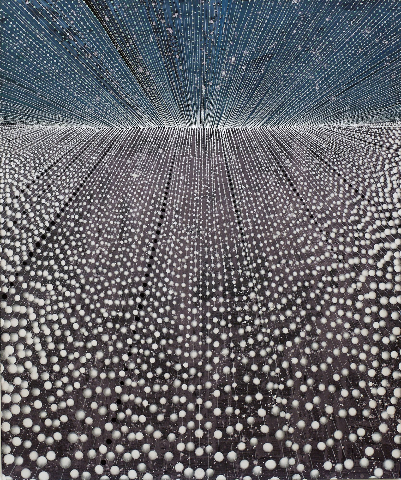

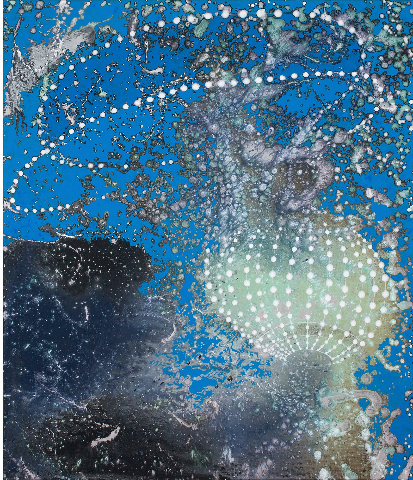

The newest works are more panoramic with the use of horizontals which are arguably horizon lines. That evokes the idea of landscapes or better spacescapes. There are no references to earthbound organic signifiers.

Some of the most spectacular works resemble images of deep space through the Hubble telescope. There are tracer lines of stars and ersatz comets.

Perhaps that is the starting point for meditations of cosmology.

Notably the artist has commented on growing up looking at the stars.

This is an exhibition more to be felt than explained. It is best to encourage the reader to see the work, stand in front of it, and be open to the experience. Your time will be well spent.

Ad astra per aspera.