Uzbekistan: Part Three

Khiva and Fergana Valley

By: Zeren Earls - Oct 09, 2013

Receiving a packed lunch from our hotel, we set out on our journey to Khiva, 500 km west of Bukhara. Traveling along the Kyzyl Kum (Red Sand) desert, separated from the Kara Kum (Black Sand) desert by the almost depleted waters of the Amu Darya River, we drove by stunted corn and cotton plants and a flock of a special breed of sheep which only survive in the desert. The rough road gave way to a paved one, occasionally dusted with sand. Taking advantage of the monotonous scenery, Nazira informed us about the health and education system of the country during the ride.

Medical service was free during the Soviet period; people only paid for medicine. Since independence, medical service has become very expensive, as only 30% is free. Due to the government’s lack of money, free vaccinations are no longer available, making contagious diseases hard to control. Tuberculosis is rampant because of overcrowding in prisons. All medicines are imported, including some from India.

During the Soviet period, the largely illiterate population began receiving eleven years of compulsory education in both Russian and Uzbek; schooling has now been reduced to seven years and is only in Uzbek. Those wishing to pursue higher education attend special schools for two to three years before starting university. Most students who are able to study abroad do not come back.

Retirement age is 55 for women and 60 for men. The unemployment rate is around 20%. Of the total population of 30 million, 5 million Uzbek men work in Russia. Most industry has moved out, leaving the country to subsist largely on agriculture, although speculative oil drilling continues.

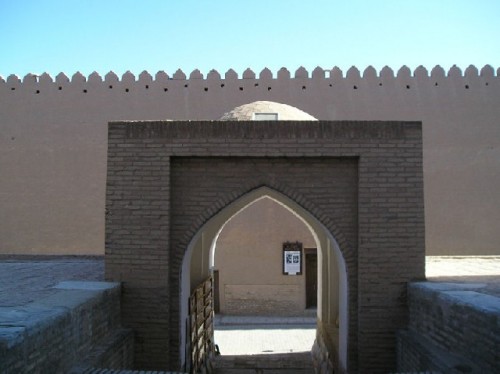

Allowing one hour for a lunch break at the only chaikhana on the road, we arrived in Khiva at 3:30 pm, eight and a half hours after our departure. Passing through the Ota Darvoza (Father Gate), we reached the Orient Star Khiva hotel at the edge of the inner city for an overnight journey back in time. A restored portal led us into the hotel, formerly the Mohammed Amin Khan Madrassah (1852-1855), connected to the Kalta (Short) Minaret, wrapped in rich bands of colorful mosaics. We reached the guestrooms — enlarged student cells — through a courtyard via twisting narrow stairways. Air conditioners were enclosed in latticed boxes, which disguised these modern additions to the historic building. Despite the care with which it had been carried out, this cultural transformation of the madrassah signaled a precedent for other hotels likely to follow, changing the purity of the museum-like city.

Khiva is a city within a city; its inner kernel, the Ichan Kala (Internal Fortress), is wrapped in a 2.2-km-long, 7-8-meter-high belt of crenellated clay walls fortified with semicircular towers and four gates. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the Ichan Kala has more than 60 architectural monuments; 2000 of the city’s 40,000 people live in the inner city. Our hotel’s location allowed us to join local life as soon as we stepped out to the street.

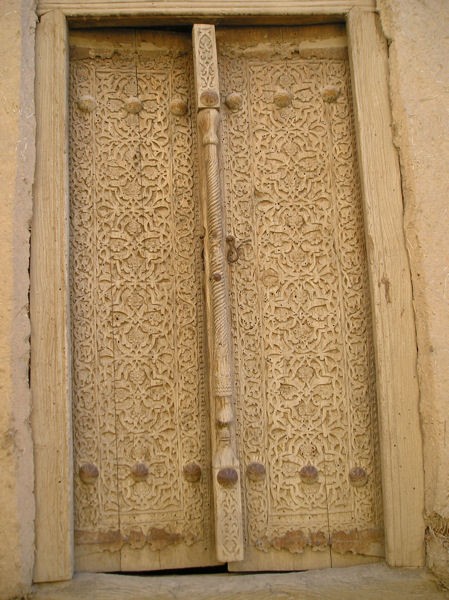

Our arrival coincided with the city’s celebration of Independence Day. Children dressed in folk costumes waited impatiently to partake in the evening ceremonies, to which we were invited. After visiting a workshop for woodcraft, which Khiva is known for, we reported at the gate where the ceremonies were being held. Pushing our way in along with the locals, we entered a large courtyard packed with people. Dignitaries, mostly men, had reserved seats facing the stage, flanked by seats for women and children.

After the national anthem, the mayor addressed the crowd, expressing his pride in the nation’s independence since 1991. He acknowledged the sacrifices that people had made to gain independence, reassuring them that the country was moving ahead and especially noting the flourishing tourism industry. The staged celebration included music, dancing, and showmanship to display the country’s might. Girls danced to the accompaniment of music by boys on traditional instruments. Teenagers put on a karate show, while soldiers displayed their bravura.

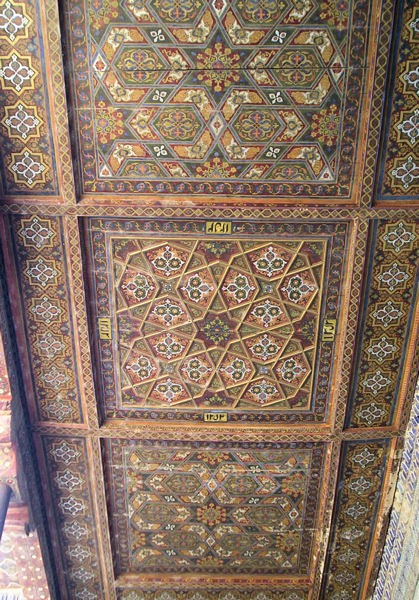

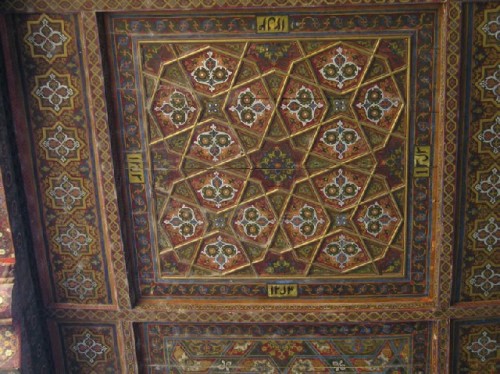

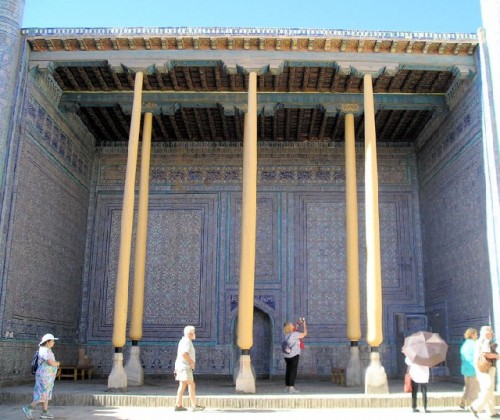

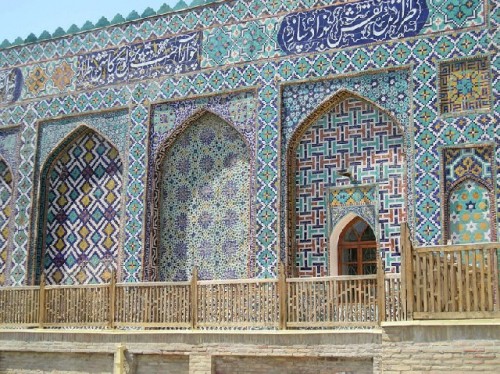

Walking back to the hotel, we enjoyed the night scene of the Ichan Kala, its monuments lit subtly to accentuate their architectural detail, which we looked forward to seeing in daylight. Our morning tour began at the Kukhna Ark, or Old Fortress, which is the inner citadel of the Ichan Kala. Separated by a high wall, the citadel provided fortified refuge for the khans of Khiva. To the right of the main entrance gate is the Khan’s Mosque (1838), decorated with masterful blue and white tiles in concentrated arabesque motifs. The Throne Room, where the khan held receptions, has ornate carved and painted ceiling decorations and a niche holding the khan’s throne. The mint displays a collection of coins, medals, and silk banknotes and a mock-up of a blacksmith’s workshop where coins were once minted. To its south is the Ak-Sheikh-Bobo Mosque, named after a saint. The simply decorated mosque has a beautiful iwan (vaulted portico), with two rows of columns and walls adorned with exquisite majolica ceramics. The grounds also house a museum dedicated to the history of the Khivan Khanate, with an exhibition of local clothes, armor, and turn-of-the-century photographs.

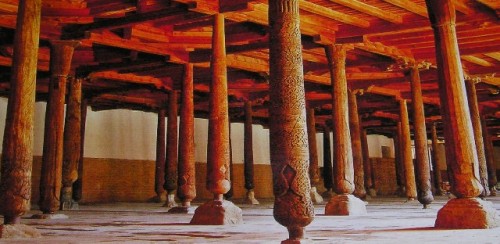

The Joma (Friday) Mosque (1788) has 213 carved karagacha (black elm) pillars, spaced 3.15 meters apart. It is an archaic structure with a flat ceiling on columns, particular to ancient Arabian mosques. Three holes in the ceiling provide light pools in the colonnaded forest, creating a subdued environment for praying. Crowned by an eight-arch cupola with a dome and stalactite cornice, its 33-meter-high minaret rises from a base 6 meters across and is centrally aligned with five other Khiva minarets, spaced 200 meters from each other.

In the southeastern part of the Ichan Kala stand the madrassah and minaret (1908-10) of Islam Khodja, Grand Vizier of the court of Isfanndiyar Khan. The Khodja sponsored the construction of many buildings, including the 45-meter-high minaret, which offers the highest observation point in Khiva. Horizontal belts of dark blue, white, blue, and green glazed mosaic decorate the minaret. Its skylight has a stalactite cornice and ceramic pandjara windows. A mosque and madrassah with 40 cells, which are now the Applied Arts Museum, complete the Islam Khodja ensemble. In 1913 the Khodja was assassinated for introducing educational reforms, including commissioning a public school.

The Mausoleum of Pahlavan Mahmoud, one of the founders of Sufi Islam, is the spiritual center of the Ichan Kala. A local furrier, champion wrestler, poet and healer, Pahlavan Mahmoud was buried, by tradition, in his own workshop when he died in 1326. In 1810 his tomb was included in a new mausoleum enclosed in a yard with a well. The walls of the necropolis, the most renowned building in the city, are saturated with tiles in all shades of blue, above which floats a turquoise dome. Pilgrims arrive to drink water from the well, pray, and leave offerings of food and money. After an early dinner and satiated with the wonders of Islamic architecture, we drove to Urgench, the regional transport hub, to catch a flight to Tashkent, 1050 km away. This would begin the next leg of our adventure to the Fergana Valley, the silk center of Uzbekistan, where one third of the population live in the flood plains of the Syr Darya River.

Spending the night in Tashkent, we flew to Fergana in the morning with Uzbekistan Airways. Within an hour we were in the valley’s third largest city, with a population of 230,000. Founded in 1876 as New Margilon, 20km from the ancient town of Islamic Margilon, Fergana assumed the name of the valley in 1924. Soviet-like in its plan, the city has wide avenues, fountains, Russian architecture, and industrial zones. As soon as we dropped off our bags at Club Hotel 777, we drove to the 10th-century town of Margilon on the ancient Silk Road to visit the Yodgorlik (Souvenir) Silk Factory.

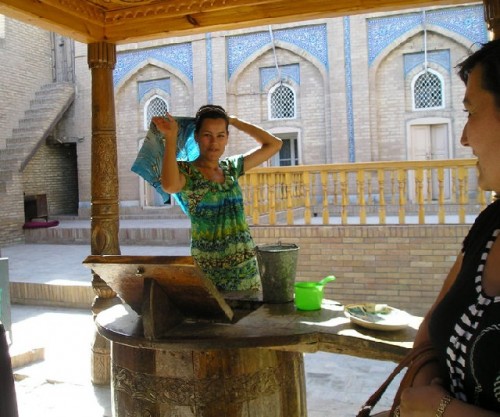

Yodgorlik was founded in 1983 by a group of artisans to preserve traditional methods of handmade silk as opposed to mass production. Individual households feed silkworms with fresh mulberry leaves until the worms spin their cocoons of silk. Before the pupae mutate into moths, the cocoons are steamed and dispatched to a factory, where they are plunged into boiling vats to soften and draw out the silk thread. We followed the process as the entire thread was carefully unwound, wrapped, and unwrapped for dying in various natural colors by men and woven into shimmering fabric by women. Our last stop was the exhibition hall and gift shop, where I bought a half-meter remnant for framing.

The next day we visited ceramic Master Rustam Usmanov’s family workshop in the small town of Rishtan, south of Fergana. Famed for its bright blue and green ceramics with the unique ishkor glaze, Rishtan is one of the oldest pottery centers in Central Asia, where the art is passed down from father to son. After watching the master’s son using local red clay at the wheel, we learned about natural pigments made from minerals and mountain grasses in the region and decorating objects with floral designs before glazing and firing. Accustomed to Uzbek hospitality, we enjoyed tea and pastry along with assorted nuts and grapes of the region. The showroom had tea sets, vases, bowls, and decorative plates for sale. Already loaded with crafts collected so far, I reluctantly limited my purchases to small objects — a bowl, a plate, and a pitcher in the shape of a duck, the workshop’s symbol.

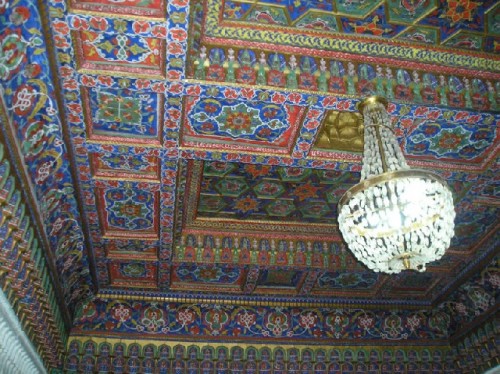

Our next destination was Kokand, the valley’s second largest city and the spiritual center of the region. Traveling west from Rishtan on a road flanked by fruit orchards, we arrived at Khudayar Khan’s Urda (Palace Citadel), which was the center of the Kokand Khanate, in the 19th century. We were met by a museum guide at the end of a ramp leading through the entrance portal of the palace with a long façade of arches and minarets glittering with colorful tiles. Similarly ornate are the interior rooms, with ceilings decorated in the diverse color and carving of traditional Fergana architecture and walls with tiled corners. There are furniture from Russia and porcelain gifts from China and Japan in wall niches.The palace museum includes artifacts such as the bust of a warrior dating back to the 6th century.

Our tour of Kokand was cut short because we had to drive back to Tashkent instead of flying, as there were no flights available to get us back in time for our flight to Istanbul. We had to travel in four separate taxicabs to simplify security clearance at checkpoints, a caution against foreign money, which finds fertile ground in the valley for brands of Islam more extreme than local governments care for. We traveled on a road blasted through the southern slopes of the Chatkal range by Soviet might in the late 50s. Our air-conditioning refused to function on the upward climbs. We stopped for a panoramic view of the valley, also enjoyed by young Uzbek men, who proudly unfurled the national flag against the beautiful view.

A supermarket stop in Tashkent helped our weary group to refuel until our departure at 3 am. In front of the supermarket, a vendor hawked corn out of a steaming black cauldron. As he sprinkled salt on the ear of corn I purchased, I could not help but think of the cultural similarities between Uzbekistan and Turkey, including corn enjoyed as street food.

Although Uzbekistan is at least fifty years behind Turkey in development, the gap is understandable considering that the Uzbek Republic is only 22 years old, whereas the Turkish Republic will celebrate its 90th anniversary this month. I hope the Uzbek government will be able to sustain its handicrafts workforce as the country catches up with the industrial and digital age. In Turkey hardly anyone embroiders any longer; most such goods are imported.

The variety of crafts I collected will help me remember Uzbekistan, a fascinating country of hospitable people with long shimmering dresses and golden teeth.