BLO's "La Boheme" Reset in '68 Paris

Period Change Does Not Diminish an Iconic Opera

By: David Bonetti - Oct 09, 2015

La Bohème

Music by Giacomo Puccini

Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, based on “Scènes de La Vie de Bohème” by Henri Murger

Premiere: Teatro Regio, Torino, 1896

Boston Lyric Opera

Shubert Theatre, Boston

October 2-11, 2015

Boston Lyric Opera Orchestra and Chorus|

Conductor: David Angus

Stage director: Rosetta Cucchi

Set designer: John Conklin

Costume designer: Nancy Leary

Lighting designer: D.M. Wood

Cast: Kelly Kaduce, soprano (Mimì,); Jesus Garcia, tenor (Rodolfo); Jonathan Beyer, baritone (Marcello); Emily Birsan, soprano (Musetta); Brandon Cedel, bass-baritone (Colline); Andrew Garland, baritone (Schaunard); James Madedalena, baritone (Benoit and Alcindoro), Omar Najmi, Brad Raymond, Mira Donahue, Ron Williams, Vincent Turregano in smaller parts

“La Bohème” is one of the most popular operas in the repertoire, which should come as no surprise. It tells the story of young love, non-conformist living, and the possibility of a utopia based on love and living for the moment, which the solid bourgeois who fill opera theaters can only fantasize – or fulminate - about. It also comes with the irresistible lyricism of Puccini at his early peak and melodies that audiences can literally walk out humming. And it clocks in at a mere two hours, not because the composer skimps on detail, but because he and his librettists don’t waste a word or a note. It would be hard to find a structurally tighter work in opera.

Opera sophisticates sometimes scoff at the frequency of “Bohème” performances, as if there is something wrong with providing audiences the opportunity to hear a masterpiece more than once in their lifetimes. But I haven’t seen a professional production of the work in nearly 20 years. It has not been produced in Boston in the five years I’ve lived here. And during the seven years I lived in St. Louis, it was not produced there. I have no memory of the production I saw in San Francisco, although I know I did see one. I checked on the San Francisco Opera website and discovered that the production I most likely saw there featured a young Mariusz Kwiecien as Marcello and a little nobody named Anna Netrebko as Musetta. Such is the nature of memory. I have a local friend who goes to everything who is avoiding “Bohème” because of its ubiquity. I asked him when he last heard it live and he thought for more than a moment and said that it was probably Sarah Caldwell’s production – 30-odd years ago. (That’s also the production I most vividly remember.) Once in a quarter century to see a masterpiece performed by live singers on a stage is not too much I would say. A regular-goer to the Met’s HD live transmissions, like many of those who are unconsciously contributing to the death of live opera, he doesn’t seem to care that those events are not live opera, but videos, skillfully produced videos taped in real time, but videos nonetheless.

The Boston Lyric Opera presented an affecting, smartly updated production, featuring good if not stellar singers. I did not cry at the end at Mimì’s death, which is the hallmark of a successful production, but I left the theater with the profound sadness that surrounds unfulfilled hopes for a better world and the early death that often rewards those who forge new pathways. Poor Mimì didn’t even live long enough to join the 27 club.

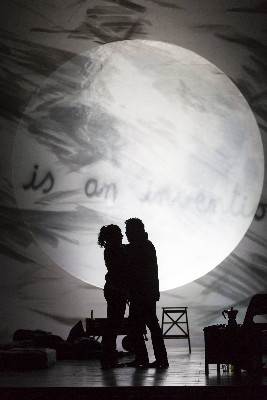

Those emotions were underscored by the updating by John Conklin, the BLO’s artistic advisor and set designer, that set the opera during the events of the May, 1968, student and worker uprising in Paris, which were echoed around the world from Prague to Boston. The transposition was remarkably seamless, doing little violence to the original. As a student at the time, I was an active participant in the local events. I was clubbed by a Boston policeman and kicked down the stairs at Park Street station during an anti-war demonstration that turned violent. Yes, dear readers, I did throw a stone at the window of a bank on Tremont Street. (It didn’t break.) The failure of those events and all the subsequent ones have broken a hardened heart many times, but hope springs eternal. There are new stirrings: the Occupy movement gave us the idea of the “one percent” and the Black Lives Matter movement dramatically makes the point of its brilliant title. The afternoon before BLO’s performance I attended the Bernie Sanders rally at the Boston Convention Center and was heartened by the huge crowd and the large number of young people there. Could the public events of the moment have effected Conklin’s decision to set the opera during another time when protest was bubbling up from the bottom?

The male characters in “La Bohème” - a poet (a filmmaker in the updating), a painter, a philosopher, a musician – were artists and intellectuals, not revolutionaries. Marxists dismissed bohemians as parasites, barnicles attached to the bourgeoisie, by an “umbilical cord of gold,” as art critic Clement Greenberg put it before he switched to pandering to the establishment. That unfortunate fact complicates the updating. It’s unlikely that you’d find Rodolfo and Marcello on the barricades, although Act III places them there instead of in lodgings at one of Paris’s city gates.

Still, it made dramatic sense, and the visual references to filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard; actors Jean Seberg, who starred with Jean-Paul Belmondo in Godard’s “Breathless,” Jean-Pierre Léaud, who played the hapless student/intellectual Antoine Doinel (the role model of my crazy youth) in Truffaut’s films and Marilyn Monroe alongside Marx and Che Guevara, creates the dramatic setting for the opera’s essentially apolitical action.

Adopting the strategies of the Situationist International, the philosophical movement that spurred the ’68 rebellion, the last leftist uprising that threatened to overthrow a government in Europe, Conklin prefaced each act with agit/prop slogans – Godard’s famous description of the ‘68 generation as “The Children of Marx and Coca-Cola” appeared on a screen before the performance. There were film clips of the demonstrations that shut down Paris and one of a triumphant Charles de Gaulle, who had fled the country at one point, declaring that everything had returned to normal, the workers to their factories, the students to their classrooms.

Conklin (with Allison Voth) rewrote the supertitles to match the updating. I’m sure that purists will object, but it kept the text in line with what was going on on stage, and if the purists are that pure, they certainly know Italian and could hear it sung unaltered. Rest assured, the texts of the famous arias were translated without undue alteration, although, as we know, all translations are unfaithful.

There were other nice touches: in the original, Marcello paints an academic-sounding work, “The Parting of the Red Sea” – these bohemians were not stylistic innovators - here, he paints a poster-like image of Che Guevara, his familiar face and beret against a bright red ground.

The staging, by the Italian Rosetta Cucchi making her BLO debut, focused on detail, and she seems to have choreographed every movement, every gesture, which paid off particularly well in the scenes of the four male bohemians in the garret basically acting like the 20-year olds they are, rough-housing, playing pranks on each other. This was not a production in which the singers stand around like opera singers pretending to act – which after decades of director-dominated productions, is still all too common. The BLO should bring Cucchi back.

But the staging was not without fault. The second act scene at the Café Momus opened promisingly with chorus members dressed in black holding familiar turquoise Tiffany-colored boxes, tempting the bohemians with bourgeois riches – a little touch of German regietheater. But the usually infectious staging of the entry of toy vendor Papignol followed by a chorus of children was seriously muddled, substituted by an array of black-and-white renderings of toys dropped from above. A seriously bad decision – I don’t know whether to blame Conklin or Cucchi, but I’m inclined to see Conklin’s hand here – after all, he was responsible for the ridiculous resetting of BLO’s “The Magic Flute” in the Yucatan. (BTW, Nancy O’Leary’s costumes were a marked improvement over her contributions to Conklin’s “Magic Flute,” in which she dressed Pamina, a princess, the daughter of the magical Queen of the Night and the sorcerer Sarastro, in a dowdy cardigan sweater. I particularly like Musetta’s luxuriously fur-cuffed and collared burgundy coat in Act II, obviously a lucky flea market find.)

The story of the opera is simple. As the Improper Bostonian recently summarized it in a preview of a video presentation at the Coolidge Corner Theater, “A poet falls for a seamstress in declining health.” Well, yes, but there is a little more to it. In addition to Rodolfo, the poet, and Mimì, the seamstress, there is another young couple that parallels their relationship, Marcello, the painter, and Musetta, a high-spirited grisette, or working class woman with negotiable virtues. And there are Rodolfo and Marcello’s roommates, Colline, a philosopher, and Schaunard, a musician. But that simple sentence in the Improper Bostonian basically nails it. Of course, the seamstress in declining health will die in the end, and, of course, her decline and death will bring out a torrent of emotion from her friends, just as in the first act the love-at-first-sight pair of arias and duet between Rodolfo and Mimí bring out a torrent of emotion of a different order.

One little caveat: In Act I, when the bohemians glumly face an impoverished Christmas Eve, Schaunard returns with a fist full of cash. His explanation: an older man hired him for three days to play his violin to make his parrot die, a preposterous story. Excuse me: don’t you think the older man might have hired Schaunard for something more than that? If working women of the time reverted to selling their bodies in order to buy food, don’t you think the men might have on occasion done so also? Since he was fearless in his tampering with the time and context, and the text itself in the translated supertitles, couldn’t have Conklin suggested as much?

The young cast made a terrific ensemble, natural and easy with each other as if they were the characters they were playing in real life. If there was no Pavarotti or Freni among them, they were all at the minimum acceptable and occasionally more than that.

As Mimì, the delicate flower soon to wither, Kelly Kaduce was not always ideal for the role. In the chance encounter with Rodolfo that closes the first act, in which the two fall in love, each singing an aria and a duet that virtually defines operatic romanticism, she lacked the requisite lyricism that should cause the audience to collectively melt, her voice thinning toward its high range, struggling to hit the top notes, noticeably at the final “amore,” a killer of a note for many sopranos. But she had her moments. When she sang about how when the first kiss of April comes she comes back to more robust life, her voice filled and soared. She was better in the second half of the program, which called for a more dramatic soprano. Begging Rodolfo at the barricades on the outskirts of town to postpone their break-up until spring, she sings with passion and power with rich, full colorful low notes. Her death scene, the bohemians gathered around her with the medicine, now useless, they have bought by pawning their possessions, is touching, but it failed to elicit the tears it should.

Tenor Jesus Garcia, making his BLO debut as Rodolfo, had what the role demands both vocally and dramatically. A self-important young artist, he filmed everything of interest when he wasn’t scribbling verse, Mimì squirming with discomfort as the subject of his camera. His voice was terrific. He sang “Che gelida manina” (How cold your little hand is), the aria that opens the sequence of arias and duet that ends the first act, with a full, sonorous voice with ringing high notes. Garcia’s and Kaduce’s voices blended in their duets beautifully.

As Marcello, Rodolfo’s main man, baritone Jonathan Beyer sang with vocal color and dramatic urgency. In his pair of duets at the barricades in Act III with first, Mimì, and then Rodolfo, he more than held his own. And in a duet at the Café Momus with his on-again, off-again girlfriend Musetta, the pair was electric.

The character of Musetta, a real spitfire, tends to raise the temperature. Soprano Emily Birsan, also making her BLO debut, was a natural at sexual provocation. Bursting through a curtain at the back of the Café’s terrace like a film star in that fur-trimmed burgundy coat, she sang with richness of tone and dramatic abandon. Her famous waltz was, as it should be, intoxicating, although it didn’t quite make me want to jump on stage and party with the bohemians who were having such a good time, like I did at the long ago Caldwell production. In Act III, when she and Marcello are bickering, they throw insults at each other like staccato stabs to the heart.

As Schaunard, the violinist who killed the old man’s parrot, baritone Andrew Garland was as good as we have come to expect him to be. As the philosopher Colline, bass-baritone Brandon Cedel, made the most of the poignant aria in which he says good-bye to his coat, which he is about to pawn for Mimì’s medicine.

And Boston veteran baritone James Maddalena endowed the two small roles of the landlord Benoit and the old lech Alcindoro with individuality.

David Angus led the orchestra with brio, appropriately reining in the overt romanticism to fit this more realistic approach to an opera classic.

A special mention to BLO dramaturg Magda Romanska, who as usual contributed intelligent essays to the program and the BLO website that enlarged our understanding of the events of ’68.