The Odd Couple Warhol and Rockwell

Populism as Commonality Explored at Rockwell Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 12, 2017

Inventing America: Rockwell + Warhol

Curated by Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and Jesse Kowalski

Catalogue: Essays by Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and Jesse Kowalski, Matt Wrbican, and James Warhola, 96 pages, illustrated

The Norman Rockwell Museum

Stockbridge, Mass.

June 10 to October 29, 2017

In a clever and evocative manner the Norman Rockwell Museum has paired an odd couple of artists. The conservative, traditionalist illustrator Norman Rockewell (1894-1978) couldn’t be more different in personality and outlook than the campy, urbane, king of pop, Andy Warhol (1928-1987).

By pairing these artists, among the most successful, acclaimed and beloved of their generation, the curators Stephanie Haboush Plunkett and Jesse Kowalski ask viewers to consider that while worlds apart, coming from opposite ends of the spectrum, they converge by presenting a richly diverse definition of American art, culture and politics. We also view images of what roiled the nation including the civil rights movement and the assassination of President Kennedy.

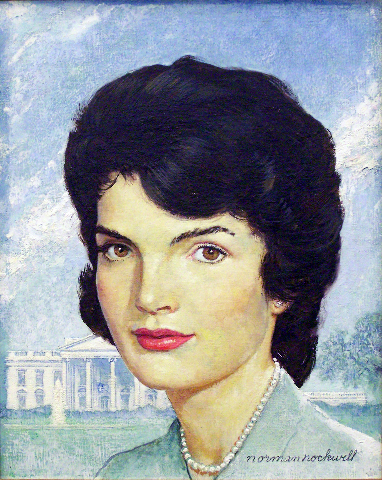

There are stunning juxtapositions. A small scale Rockwell portrait of Jackie Kennedy for a Saturday Evening Post cover is displayed next to two, ripped from the headlines, views of the former first lady in silk screened images. They depict a smiling Jackie arriving in Dallas and the second is cropped from a press image of a grieving widow taken when Lyndon Johnson was sworn in. The moment occured on Air Force One during the return flight to Washington, D.C.

The drawing power of Rockwell is legendary in the Berkshires. The pairing with Warhol, while perhaps lost on most visitors, is just sublime.

Passing through Stockbridge on the way to the museum the leaf peepers were out in force. On a mid week afternoon the museum was packed with pensioners. There were several tour buses in the parking lot.

Yet again there was a sense of claustrophobia in galleries that are densely filled with work and small in scale relative to the number of visitors. Arguably, when designed by the renowned architect, Robert A. M. Stern, nobody anticipated that it would be so well attended.

A staff member commented that it has indeed been busy with some 1,800 visitors per day on the prior weekend. For a relatively small, regional museum, those attendance figures are far in excess of the norm.

Largely through using neighbors and the main street of Stockbridge as models and settings for his covers and illustrations the artist branded the town and the Berkshires as a paradigm of Americana. With its historic Red Lion Inn and other landmarks Stockbridge, as depicted by Rockwell, has become a resonating signifier for rural, picture postcard America.

This has never been more evident than through controversy and backlash of the decision of the Berkshire Museum to sell two of his paintings along with 38 other objects from the collection. It also includes key works by 19th century Hudson River artists but the headlines of national and global coverage have focused on Rockwell. The artist personally donated two works to the museum on behalf of the community. There was an implied trust that is now being violated.

In November, when the works are sold at Sotheby’s with a barrage of media attention, there will be a dollar value placed on the impact that publicity has had on the equity of the work and the artist’s reputation.

If you come to the museum's exhibition with assumptions that you know the work of these artists be prepared for delightful surprises and fresh insights.

What is most enjoyable about the project is its delving into archival family photographs and ephemera including studies and the thinking process for finished works. You will be shocked to see Andy's early representational work. Particularly amusing is Nosepicker II from 1948. The wacky picture, showing the influence of Ben Shahn, was submitted to but rejected for a juried exhibition. That compares to a similar result when Marcel Duchamp submitted a urinal titled Fountain.

A vitrine juxtaposes opaque projectors used by the artists. These cumbersome devices allowed the artists to put photos and book illustrations in and then project them onto tacked up sheets of paper or canvases. That facilitates accurately tracing and sketching details as part of the drawing process.

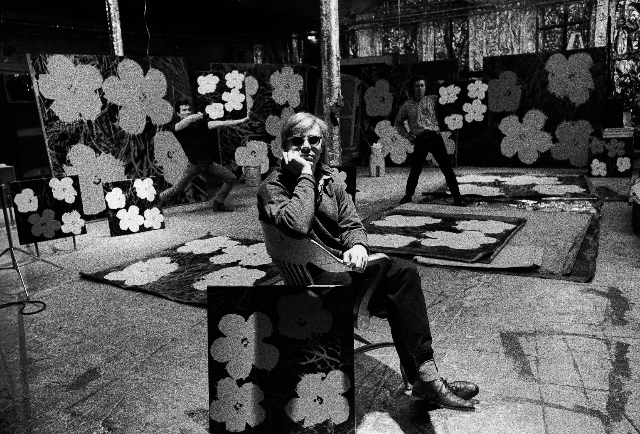

For Warhol, who started as a successful commercial artist, this device was abandoned when he developed work with photo derived silk screens on paper and canvas. He continued to do occasional commercial work but focused on gallery exhibitions. The exhibition includes album covers for his house band, The Velvet Underground, and the real zipper design for Sticky Fingers by the Rolling Stones.

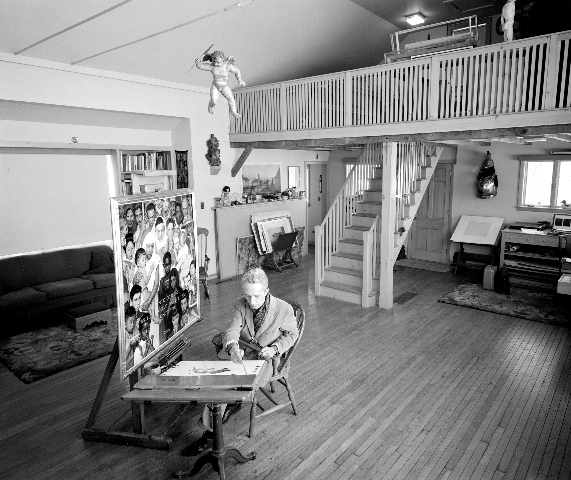

While Rockwell labored alone in the studio creating meticulously rendered works, when Warhol hit his stride, the artist employed a Factory of hipsters and hangers-on for projects from silk screens to cinema.

Initially, Warhol had a single assistant, the poet Gerard Malanga. Together they worked on now seminal series like the Brillo Boxes. Gerard was paid but most of the Factory entourage got free meals on Andy’s tab at Max’s Kansas City. It was a short walk from the silver painted studio in Union Square. There was always high drama when Andy and his entourage entered, brushing past the bar for the back room under a light sculpture by Dan Flavin. Poet Renee Ricard was known to dance on table tops. Upstairs punk bands like the New York Dolls performed.

Armed with a tape recorder and Polaroid camera Andy documented the scene at Max's and uptown at Studio 54. Tapes, snap shots, the daily mail, promo items, press releases and party invitations were tossed into boxes which were sealed and taken to a warehouse. The Time Capsules are now in the collection of the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh where he was raised. Like Duchamp before him Andy's life in all of its facets became a work of art.

Using silk screens allowed Warhol to create an enormous amount of work compared to the one-of- a-kind paintings and drawings of Rockwell.

While similarly masters of popular culture, with a vision and mandate for reenforcing notions of American, Rockwell played it straight and looked us in the eye, while, with a wink and nod, there was always a touch of irony in the work of Warhol.

Basking in the klieg lights of fame and celebrity Warhol was a master of self promotion. Many in the Berkshires fondly remember Rockwell as an understated friend and neighbor. His work was regularly seen on the cover of mass media magazines. Rockwell came in the mail to our homes. Both artists were beneficiaries of marketing and mass media.

There is a misconception that because they were so famous we know all about them. There are elements of this exhibition that disabuse us of that conceit. One should pay particular attention to the family photos. We see Rockwell with his children of whom Jarvis is a neighbor in North Adams. Andy is shown in images of the Warhola family. He was a sickly child and may well have suffered torment that encouraged him to write to movie stars. They later became a part of the work. In the Factory he created his own superstars and Girl of the Year starting with the tragic, Berkshire-based Edie Sedgwick.

It is curious to see the work clothes of Rockwell and Warhol displayed side-by-side. There is Rockwell’s generic country duds, a plaid shirt and nothing fancy, compared to one of Warhol's silver wigs.

From adolescence, because of chronic illness, Andy was bald, pasty-faced and homely. He learned to use wigs in amusing combinations. He created a deception of bleached silver hair and that black roots were growing back. The trick made one assume that it was his real hair.

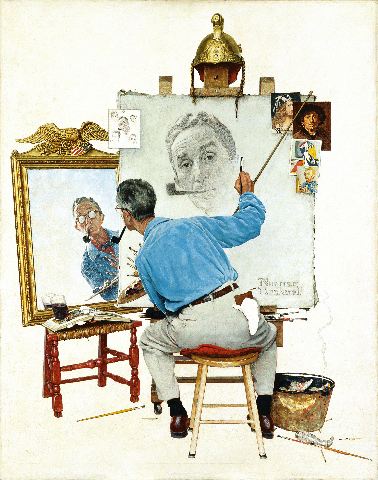

Both artists created fascinating self portraits as a part of their personas and advertisement. It is a familiar theme for artists from Rembrandt to Van Gogh. Rockwell depicts himself at the easel staring into a mirror. There are sketches and studies tacked onto the wall.

In the same manner that he produced iconic images of Marilyn Monroe, Liz Taylor and other stars, Warhol mass produced well crafted, slick, graphic self portraits. It was clever as both self promotion and a marketable product.

Pride of place in the center of the main gallery is Freedom from Want a February 20, 1943 Saturday Evening Post cover by Rockwell. It depicts a grandmother placing the roasted turkey on the table. Behind her is the beaming grandpa. The family is gathered round for a holiday meal with a man in the lower right corner looking out at us as viewer, photographer or painter. In the device of theatre it breaks the fourth wall.

In that iconic image Rockwell depicted an America we all want to believe in. It is also a target for parody as it focuses on a white, middle American family enjoying a feast. The world was at war and there were few such bounteous feasts or celebrations. Here we see the artist as propagandist extraordinaire. Arguably, the uplifting image was meant to boost the national spirit. As a part of the war effort there were rations for food staples like meat, coffee, butter and sugar as well as gasoline.

That makes all the more significant the application of Rockwell's considerable skill and vast audience to the cause of Civil Rights. In the plethora of commercial illustration in the galleries we are stopped in our tracks by The Problem We All Live With, 1963. It was a 1964 cover for Look Magazine. The illustration depicts a black child in profile, neatly dressed in crisp white accompanied by U.S. Marshals. She is escorted to school during desegregation. The wall behind her spells out Nigger and there is the stain and splat of rotten tomatoes. The image is poignant and harrowing.

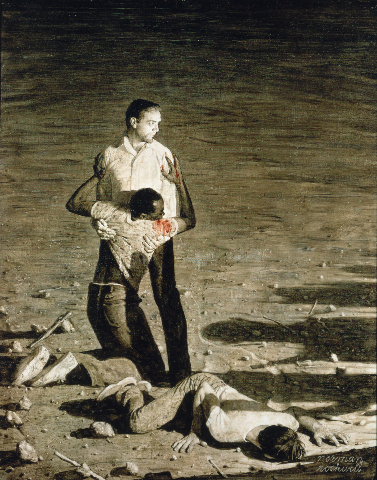

Far more explicit and horrific is an image I had never seen Murder in Mississippi 1965. It is an unpublished illustration for Southern Justice by Charles Morgan, Jr. It was published by Look Magazine on June 28, 1965.

Painted in grisaille the work is a masterpiece of meticulous photo realism. We assume it was copied precisely from a news image. There is a white man dead on the ground and another standing white man is supporting a black man on his knees. Against the rendering in black and grey the red of blood on the right arm of his t shirt pops out at us. The shadows of assailants, as well as the shape of a rifle, encroach from the right edge of the painting. Here we see the depth of the social conscience and outrage of the artist. He took a stand by depicting the dark shadow cast on the American dream.

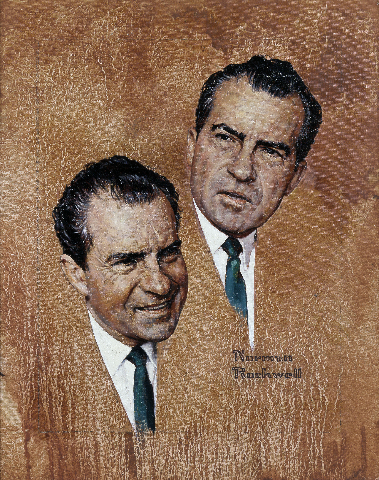

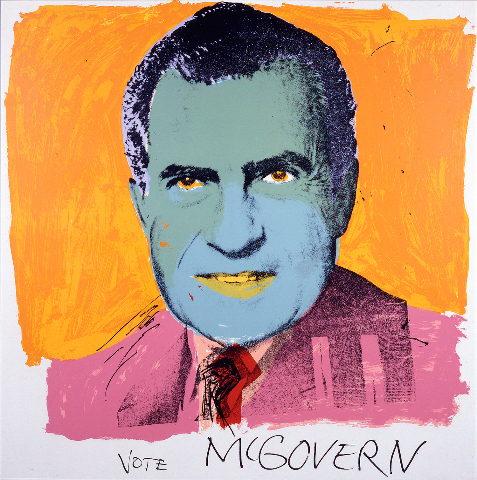

Similarly, using the graphic techniques of pop art Warhol created images such as Race Riot 1964. His 1972 poster Vote McGovern is a delicious depiction of Tricky Dick Nixon in horrifically mordant colors.

There is a sidebar gallery displaying illustrative works, many reflecting on his famous uncle, by James Warhola. It is interesting to note that talent ran in the family.

Both Norman and Andy became rich and famous for a shared populist vision. They were commercial artists in every sense. In the context of this exhibition, in the museum that bears Rockwell’s name, they are presented to us a fine artists. It is an identity that posthumously has been imposed on Rockwell. For Warhol it was a career decision to abandon advertising and focus on the fine arts.

After he was shot by a radical feminist, Valerie Solanis, Andy distanced himself from the freaks and oddballs of his inner circle. His hangout shifted from downtown at Max's to uptown with the rich and famous at Studio 54.

When he recovered he focused on making money charging top dollar for silk screen portraits of socialites and industrialists. His careeer as a producer of underground films was costly. For the late career of Warhol it was all about money. That was tempered however, by collaborations with much younger artists like Jean Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Francesco Clemente. It sparked a comeback cut short by complications following surgery. The hired private nurse spent the night reading the Bible rather than tending to her patient.

As with other leading pop artists his work embraced the theme of consumerism. The Campbell’s Soup Can, 1969, may be a witty and ironic comment on mass marketing but it has the curious default of promoting the product he is having fun with. While he created parodies we see a Kellogg's Cornflakes box designed by Rockwell.

There is a double take and unsettling response to seeing Rockwell and Warhol paired as artists.

Consider Rockwell's Art Critic used for the April 15, 1955 cover of Saturday Evening Post. A young artist, with his equipment slung over a shoulder, is leaning forward to examine a detail of a portrait in the manner of Rubens. Its subject, like the one illustrated in a book held behind his back, is a woman who appears to be smiling at him. There is a similar response from gentlemen in a Dutch masters painting hanging behind him.

This crisply rendered art about art parody underscores the artist's self conscious relationship to the fine arts. By contrast Warhol embraced the conundrum and brought commercial art into galleries and museums.

That challenge and dilemma informs and underscores this fascinating exhibition of new best friends, Norman and Andy. The curators have allowed us to combine them in a sentence that doesn't seem ridiculous.