Istanbul Biennial 13th Edition

Conjuring Art out of Socio-Politics

By: Zeren Earls - Oct 14, 2013

Since its inception in 1987, the Istanbul Biennial, organized by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and the Arts (IKSV) and fueled by the generosity of art patrons in the city, strategically positioned between East and West, has helped the rapid rise of Istanbul as a cultural power, establishing its importance for transcultural dialogue. The 13th Biennial, curated by Fulya Erdemci, currently Director of the SKOR Foundation for Art and Public Domain in Amsterdam, accentuates this dialogue with the participation of 88 artists and artist collectives, fourteen of which are from Turkey.

The exhibition, “Mom, am I barbarian?” which borrows its title from poet Lale Müldür’s eponymous book, explores the notion of public space as a political forum and focuses on the artist’s role within it. By providing a platform for our global present, the exhibition aspires to elicit a rethinking of the concept of public space and contribute to engagement and discussion of our future world. When political unrest erupted in May over Istanbul’s Gezi Park, one of the selected sites for staging Biennial projects, the curatorial team decided to withdraw entirely from the public domain by moving all Biennial exhibitions indoors. Miss Erdemci decided that “not holding them is a more meaningful statement than having them materialize under such conditions” and preferred to “mark presence through absence.”

Although admission to all five indoor Biennial venues is free of charge in order to reach a wide audience, the unexpected encounter of local people with public art is compromised, missing the chance to capture the public’s imagination, by limiting the viewing to works that comment on the dynamics of public space rather than actually using it. The exhibitions are located in five indoor venues — Antrepo 3, the Galata Greek Primary School, ARTER, SALT Beyoglu, and the IMC 5th block, two of which are private galleries.

A giant wrecking ball suspended from a crane greets visitors at the entrance to Antrepo 3, an industrial warehouse, which is the Biennial’s main venue. A green buoy pounds against the concrete facade of the building over and over at hourly intervals. Turkish artist Ayse Erkmen, with her installation titled bangbangbang, references the city’s urban transformation, including the earmarked demolition of the warehouse to make way for a waterfront hotel.

The cavernous space of Antrepo 3 drowns most of the work sheltered indoors. From Istanbul to Lima, Guadalajara, New Jersey, Palestine, Sao Paulo, and others, many pieces take the visitor on a world tour of urban change and its related social injustices. Most exhibits appear tinted by the ongoing political turmoil in Istanbul. The cumulative effect of the sheer number of complex text– based ideas is a bewildering cacophony; most of the pieces, which blur the boundaries with social documentary, lack the power to transform the viewer’s perspective.

Among the exhibits that offer engaging dialogue are Come out and Play by Maya Ersan and Jamie Robson, depicting a white paper cut-out of Istanbul’s Taksim Square and the surrounding high-rises with colorful additions to the cityscape by children. Light projected onto the paper-city replicates it in giant shadows on the wall. German artist Christoph Schafer’s large-scale drawing, Bostanorama, depicts the Marmararay Tunnel Excavation through Istanbul’s Stadiums, Parks and Gardens, present and recently destroyed.

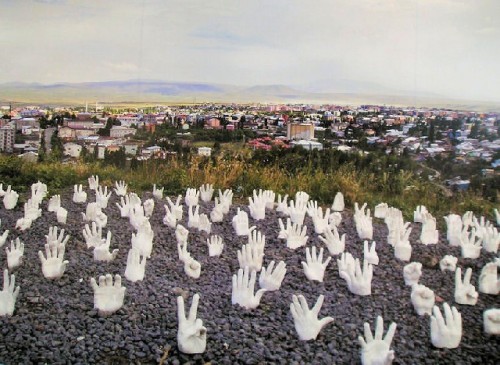

A display of photographs, Monument to Humanity: Helping Hands shows how Dutch duo Wouter Osterholt and Elke Uitentuis made an alternative monument with the participation of residents of Kars, on the Armenian border, upon hearing of the demolition of a controversial work meant to symbolize war and peace. The original, by a Turkish artist, was taken down before completion on orders from the Prime Minister. Circulating an oversized cast hand in a wheelbarrow, artists asked people’s opinions on the scandal and made casts of their hands. These hands were installed on the site of the demolished sculpture, where they were instantly removed by police.

New York-based David Moreno’s wall installation, Silence, is composed of paper cones resembling megaphones, which are placed on the loose pages of a book, composed of death masks. The cones are attached to the lips of the masks; virtually raising their voices, while at the same time intensifying their silence. Moreno’s artistic expression invites the viewer for reflection by questioning the introversion of the image, each time calling for the erasure of one’s own trace to make room for an outward expression.

In The Castle, an installation by the Mexican artist Jorge Méndez Blake, a long brick barrier representing the site of power traverses the room, with a copy of Kafka’s eponymous 1922 novel tucked underneath. While referencing Kafka, the book also interjects an imperfection in the wall, implying a reign of absurdity and arbitrariness. A respite from the buzz of the large hall is the installation Intensive Care by Erik and Ronald Rietveld, brothers who form the Dutch Landscape collective. They initially proposed an installation in which thousands of tiny lights would flicker on the façade of the Ataturk Cultural Center, a landmark in Taksim Square. Instead, the work’s new home is a small dark room in which lights play against a tiny scale model of the building.

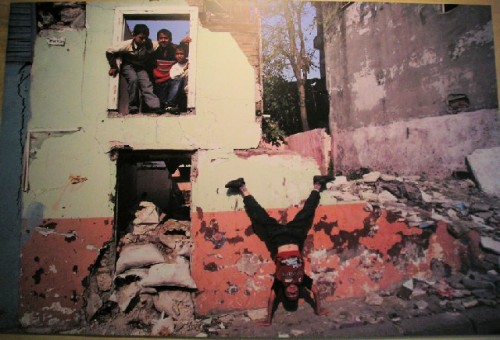

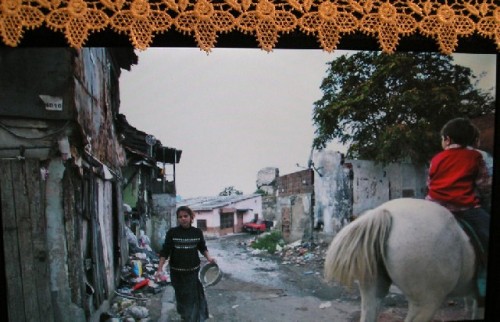

The arresting video Wonderland, by Halil Altindere, voices the frustration of Roma forced out of Istanbul’s Sulukule district by development that raised house prices tenfold. Responding to the visual idiom of the street, a darkly humorous hip-hop video shows mechanical diggers and a symbolic burning of state power in the form of a security guard set on fire.

Weighed down by the stories of the world’s oppressed and excluded which I had experienced at Antrepo 3, I walked over to see new public art next door in the courtyard of Istanbul Modern, the city’s contemporary art museum. Created by young architects, Sky Spotting Stop hovers over the courtyard of the museum, providing shade while floating gently on the hidden waters of the Bosporus. The gentle motion of the waves is transferred to the movement of the courtyard’s canopies, supported by buoys floating in water beneath the ground. Visitors rest on stacked recycled tires covered with fishnets in the undulating shade. A barren courtyard, thus transformed, provides a haven from the bustle of the city.

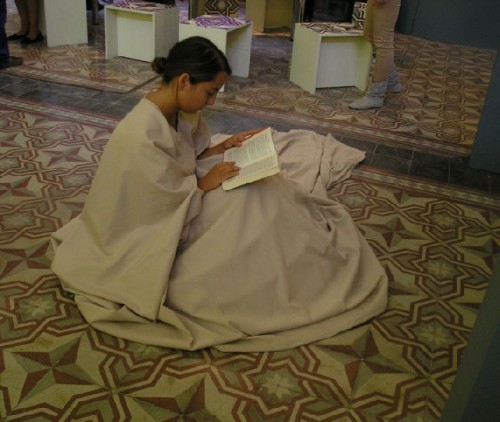

There was more art conjured out of socio-politics at the Biennial exhibitions in the Galata Greek Primary School, partially due to its intimate spaces on three levels. On the ground level is Co –Action Device: a Study by Inci Eviner, where the artist and participants constantly exchange roles. While performing as part of this work, students from various disciplines have a chance to experience a variety of concepts within a creative research-production relationship. Their formations, based on performative research, are observed from galleries above.

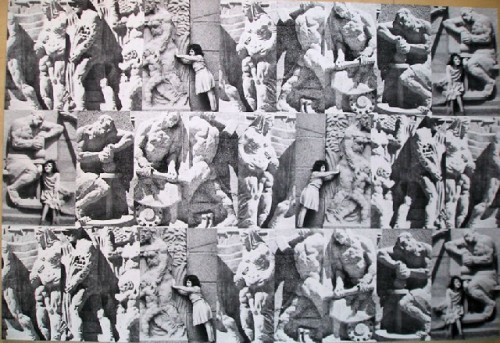

Up a stairway straight ahead is a large, arresting photographic image, Optical Propaganda, showing artist Sener Özmen in a suit made of kefiyyeh, the square patterned wool scarves traditionally worn on the head by Arab and Kurdish men. He relaxes on a couch, almost disappearing into the pattern. Along with another image, My Suit, with a modern cut of the same cloth, the artist uses the kefiyyeh as a symbol for political resistance subsumed into mainstream society. “Are we prepared to take a stance for our beliefs, or do we simply adorn ourselves with these accessories?” he queries.

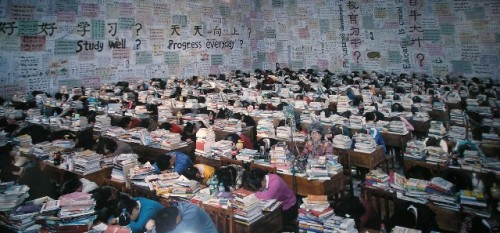

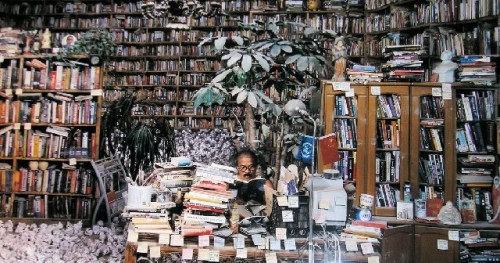

Other sizeable arresting images are color prints by Chinese artist Wang Qingsong. In Follow You, we see students; all but one crouched over piles of books, an ironic critique of the modern Chinese education system. Follow Him again speaks to the issue of education, depicting a vast number of discarded textbooks, with a lonely figure in the middle overcome by the material.

In Domain, Argentine duo Martín Cordiano and Tomás Espina create the replica of an apartment, depicting everyday life, but frozen in time. A clutch of broken objects and a photo of Che Guevara stuck in a cracked mirror betray psychic fragmentation, which could be socio-political or a breakdown of the self. The restoration with the crack marks still discernible could be a metaphor for social or individual healing, showing the impossibility of erasing the scars, yet the ability to keep moving forward.

Berlin-based Annika Eriksson’s I am the dog that was always here, a video of stray dogs exiled to the outskirts of Istanbul, is a fictitious fragment of reality focusing on moments of transition and marginalized experiences, as seen through the eye of a street dog. Transported by the authorities to peripheral pockets and no man’s lands outside the expanding city, dogs are continuously moving along the lines of gentrification and corporate city-making.

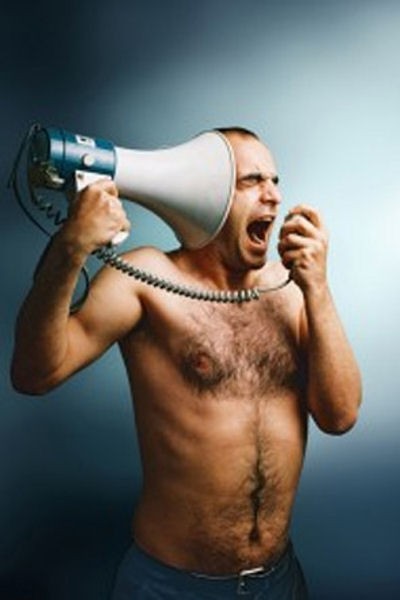

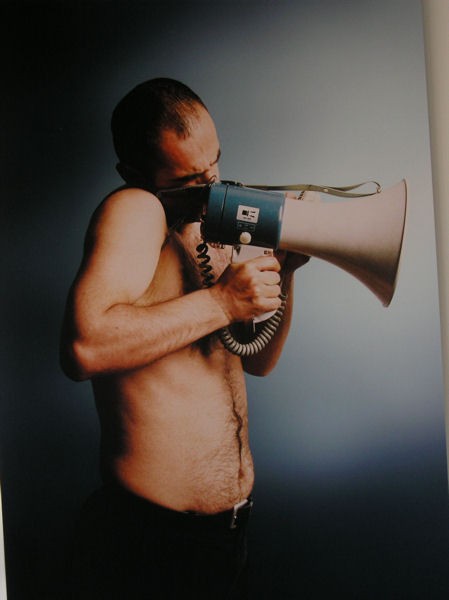

On the top floor of the Greek school, Sener Özmen has another photographic series, Untitled, depicting the artist himself aggressively shouting with a megaphone pressed against his own ear, an ironic reference to the inability to address anyone but one’s own kind. Another photo in the same series shows the artist using a megaphone transformed into a gun, once again taking a critical stand.

The first target of large-scale urban transformation in Istanbul was the Sulukule neighborhood, located within the World Heritage Site city walls and one of the oldest Roma settlements in the world. Founded in 2007, the Sulukule Platform, renowned for its ongoing urban struggle, tells its story through video installations, photographs, and hand-outs — all houses were bulldozed to make way for new structures, while ethnic populations were transferred to new housing in high rises on the outskirts of the metropolis of 14 million.

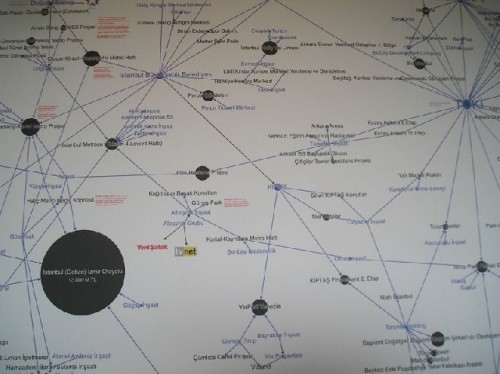

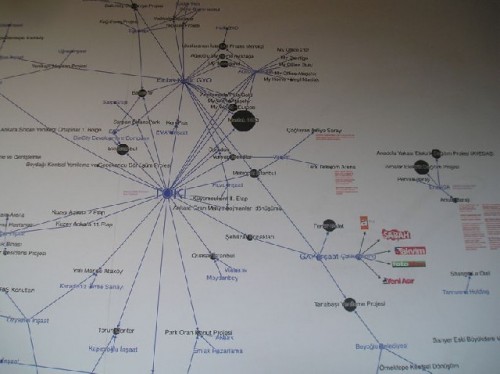

Networks of Dispossession, by a collective of Istanbul artists led by Burak Arikan, uses a digital mapping program to reveal the network of connections between state power, business, and media conglomerates — including Eczacibasi Holding, sponsors of the IKSV foundation, which organizes the Biennial — that are partners in developing the city. In this network map, corporations are colored in blue and their board members in black. The size of each name is determined by the centrality of the corresponding actor within the network. The map organizes itself through a software simulation where names naturally find their positions on the canvas through connecting forces, revealing central actors, indirect links, and clusters. Another map aims to visualize the dispossession of minority foundations through state policy since the beginning of the Republic.

In Salt Beyoglu, the first floor gallery space is dedicated to Argentinean artist Diego Bianchi. His installation, Market or Die, is meant as a comment on the surrounding mercantilism in Istiklal Caddesi, Istanbul’s main pedestrian street. The work features rubbish scattered around the edges of the gallery floor and on walls — empty cans, cigarette butts, stale bread, mannequin arms and legs, towers of muscle shells, roasted corn cobs, etc.

Upstairs in the gallery is A Promised Exhibition by pre-eminent Turkish artist Gülsün Karamustafa, whose work addresses issues of migration, displacement, sexual identity, and the military dictatorship of the 1970’s, when she was imprisoned. Among the works on display is Double Reality, a boy mannequin with a broken arm in a pale pink dress; a large black and white photo, The Monument and the Child, depicting the might of the Republic at Guven Park in Ankara and the artist as a child pushing against it; and Etiquette, a banquet table set with gold-rimmed glasses and porcelain dishes, embossed with photos from a book on etiquette, referencing Europeanization of the early Turkish Republic.

A Promised Exhibition is on view until January 5; the Biennale closes on October 20th, one month earlier than originally intended, due to loss of ticket revenue because of the decision to make admission free of charge. In the meantime, spontaneous public art erupts in unexpected places. Recently a retired engineer painted one of Istanbul’s steep flights of stairs in rainbow colors. Disapproving of the act, the municipality painted over the stairs in gray. Protest ensued and people started painting public stairs across Turkey. To calm the waters, the city repainted the original staircase in colorful stripes.