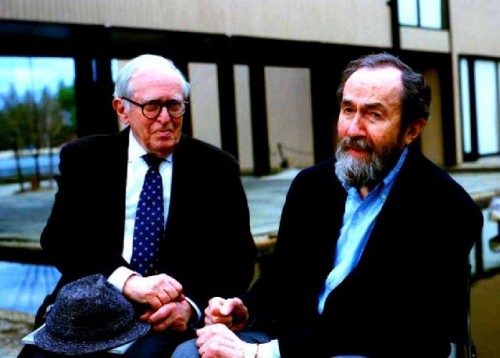

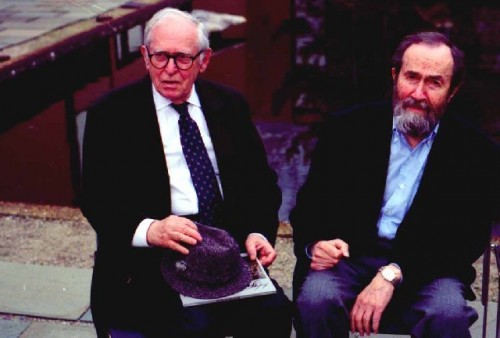

Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine

Legacy of Boston Expressionism

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 15, 2010

On September 13 the exhibition "Hyman Bloom a Spiritual Embrace" opens at the Yeshiva University Museum, 15 West 16th Street, in New York City. It remains on view through January 24, 2010. The project, which was curated by Katherine French, originated at the Danforth Museum. It serves as a memorial to a founding member of the movement of Boston Expressionism who died at the age of 96 in New Hampshire on August 26. Hyman Bloom was born in 1913 in Brunoviski, a Latvian village not far from what is now the Lithuanian border. In 1920, he and his parents immigrated to the United States.

While a boy Bloom, and his friend, Jack Levine (born in Boston, January 3, 1915 of Lithuanian parents), studied art in the West End Community Center with Harold Zimmerman. He had unique ideas about drawing from memory and imagination. When it was recognized that the boys had unique talent they were presented to Professor Denman Ross of Harvard University. Works by Ross are on view in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum which was a second home to the boys.

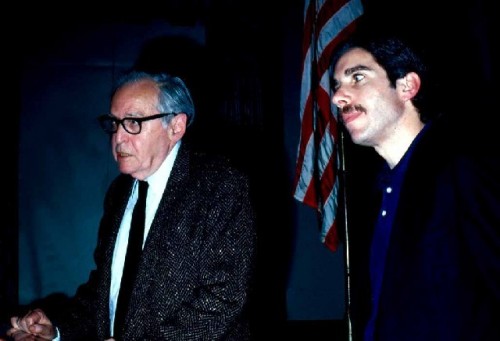

Some years ago, when David and Nancy Sutherland were shooting a documentary "Jack Levine Feast of Pure Reason" (1989) I spent a lot of time with them. Although Jack and Hyman viewed art critics as anathema, with good reason, I got along well with Levine and wrote features for Art New England (Perspective, December, 1984, page 3, Interview with Jack Levine, October, 1986, pages 6-8)) that he thought were not bad.

There was less luck connecting with Bloom who had terms that were unacceptable. He would not allow the use of a tape recorder or even for a visitor to take notes. It was understood that he would not show any work in progress. I declined. Dorothy Thompson made many visits to Bloom and quickly wrote down what had been said once she returned to her home. Thompson curated the retrospective at the Fuller Museum of Art in 1996. There was also a Bloom retrospective at the National Academy of Design, in New York, in 2002.

With Jack and the Sutherlands we spent an afternoon in the drawing department of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University. Denman Ross donated many of the drawings that the boys had created to the collection. It was fascinating to view those early works. In particular I recall a very skillful rendering of a cellist. On assignment from Ross he had created it from memory after attending a performance at the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Another drawing contained the complex lines extending the Golden Section. I asked Levine if Ross had taught them the rules of Dynamic Symmetry developed by Jay Hambridge? Jack confirmed this but dismissed it as an exercise.

During the visit Agnes Mongan, the curator of drawings at the Fogg, chatted with Jack about when he had been a student. Levine liked to quip that he and Hyman got everything from Harvard but a degree. The drawings in the collection would be the subject of a superb exhibition. So far that hasn't happened. It is also a scandal that the Boston Expressionists have never been shown individually, or as a group, at the Museum of Fine Arts.

There were several major MFA exhibitions tracing Boston Artists from Copley to the Impressionists. But the series halted precisely when the dominating Boston Artists, starting during the WPA era of the Depression, were Jewish- Bloom, Levine, and Karl Zerbe. They in turn inspired younger Jewish artists including David Aronson, Kahlil Gibran (nephew of the Lebanese poet) Arthur Polonsky and Henry Schwartz. Their legacy was extended as influential teachers at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston University, and Brandeis University.

Many of these artists showed with Boston's Boris Mirski Gallery and later the Hyman Swetzoff Gallery. It was well known that Boston had a bias for Germanic Expressionism. Harvard formed its renowned Busch Reisinger collection. Under founding director, James Plout, the Institute of Contemporary Art showed expressionism including the first American exhibition of work by Oskar Kokoschka. The Austrian artist also taught briefly at the Museum School leaving a lasting influence. Later, when Tom Messer was director of the ICA, he mounted the first American exhibition of Egon Schiele on Soldier's Field Road. I recall being shocked by that work. While I was a student at Brandeis Polonsky often discussed the work of Bloom. And the head of the department, Mitch Sipporin, brought in Levine as a visiting artist. That first exposure to Jack made a deep impression as I tried to paint like him.

In many ways I grew up with Bloom and Levine. They cast a long shadow. In 1964, I attended Harvard's Summer School studying chemistry which I had failed at Brandeis. It was the last gasp of the pre med that my parents, both doctors, insisted that I pursue. Hanging out in the Yard I met Judy Goldberg. She told me about her father's collection. During a visit I was stunned to see so many drawings by Bloom. One of which, a sepia, conte crayon rendering of a young woman split open, was hung on the inside of a closet door. It was too disturbing to be shown openly. The drawing related to "The Hull" a harrowing painting owned by the Worcester Art Museum.

Taking time to talk with a student Mr. Goldberg related how on a whim he bought a couple of Bloom drawings from Hy Swetzoff. Not long after there was a request to loan them to a museum exhibition. That confirmed that he had made a wise purchase. It became a passion and Goldberg related how collecting meant not taking vacations. That idea really moved me.

Later when I developed as an artist and evolved into becoming a critic and curator those deep roots in Boston Expressionism informed my taste, thinking, and passion. Trust me, it has not been a career move. Being an activist for figurative expressionism has been at best marginal. It doesn't come with perks. Except perhaps for appreciation by a small circle of like minded individuals.

The Danforth Museum under Katherine French has become a haven for this great but neglected tradition. It is ironic that she has assumed leadership in this narrow field. And pathetic that the legacy has been snubbed by the MFA, Fogg, and even the ever muddled DeCordova Museum. Early on in the tenure of former DeCordova director, Paul Master Karnik, there was a badly bungled attempt to survey "Expressionism in Boston: 1945 to 1985" curated by Pam Allara. At the time I wrote a blistering review for the Patriot Ledger.

Ironically, the review had just been posted when I was invited with the Sutherlands to dinner with Dorothy Thompson and her husband. She read it in the kitchen between courses. I expected to get tossed out the door. It actually initiated a lively and sustained dialogue. But she was more focused on Bloom than the larger issues of Boston Expressionism.

In the obituaries (New York Times and Boston Globe) much has been made of the fact that Bloom was acknowledged by Pollock and deKooning as a proto Abstract Expressionist. He showed at MoMA and the Venice Biennale. Initially, he drew the interest of the influential critic Clement Greenberg. But Bloom and Levine were not careerists. They seemed to have a knack for making all the wrong moves. God love them.

Returning home from the War Jack moved to Manhattan. But remained loyal to the Red Sox. Bloom stayed at home but moved into outer space. Or, more correctly, inner space. Briefly, we shared a shrink, Dr. Max Rinkle, who gave Hyman pure Sandoz lab, LSD. I had no such luck. He seemed more interested in tapping my knee to test the reflexes. I asked him about Bloom but never got an answer. Once I whispered into Hyman's ear "Dr.Max Rinkle" just for fun. Again, no response.

Jack and Hyman are lumped together as Boston Expressionists. It's just not true. Perhaps for Bloom, in phases, but no way for Levine. He is more of a satirist. In masterpieces like "Gangster's Funeral" "The Feast of Pure Reason" or the later, hilarious "Sinatra in Vegas." Sure Jack has painted the occasional Rabbi and Old Testament subjects but Bloom wallowed in Judaica as seen in the current Yeshiva show. As Jack told me "I came by my Biblical imagery honestly."

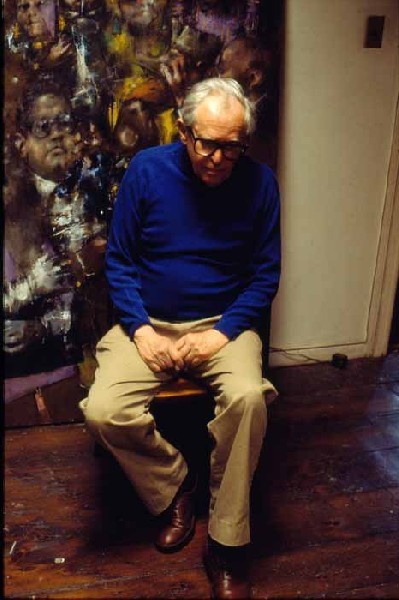

Arguably, Bloom will be best remembered/ reviled for the autopsy paintings and drawings. Early on he had a job in the morgue at Mass. General Hospital. The drawings evolved from memories of those experiences. There is an aspect of the work that relates to the mysticism of Kahlin Gibran, the elder, who he surely knew and was influenced by. I saw a number of these works in the nephew's collection as well as examples in the Telfair Museum of Art in Savannah.

Non Western art, music, and religion were seminal concerns for Bloom. This was fueled by the visions evoked by LSD sessions. The result was a snarl of dense works including psychedelic fish skeletons or drawings of New England Forrest. A show of these large latter works was mounted by the Whitney Museum and traveled to the Boston University Art Gallery in the late 1960s. It was the subject of one of my first reviews for Boston After Dark which later became known as the Boston Phoenix.

In more recent years, in addition to the Rabbis, Bloom painted curious still lifes that recalled the Belgian artist Ensor.

Surely Bloom might have been more celebrated. But you sensed that he was too self absorbed and spiritual/ mystical to give a fig. Much of the neglect was self imposed. Those rules and demands made him difficult to approach. He was most fortunate to have a wonderful wife, Stella, who managed his affairs. You sensed that they lived well.