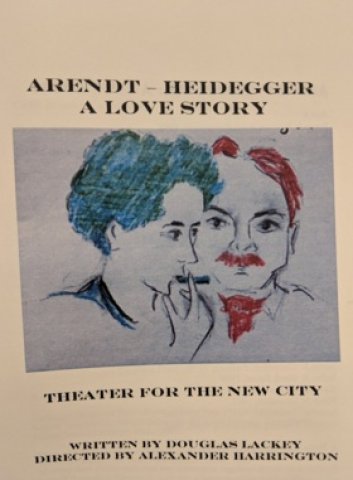

Arendt/Heidegger by Douglass Lackey

A Love Story in Ideas at Theater for the New CIty

By: Rachel de Aragon - Oct 15, 2018

Arendt/Heidegger, A Love Story, is a remarkable knitting of history, philosophy and romance by Douglas Lackey, playing at the Theater for the New City.

The set creates comfortably evocative surroundings which combine scrims, overhead screen photos and understated period-piece furniture. The production team; Marsh Shugart, Lianne Arnold, Asa Lipton, Joyce Liao, Courtney Fenwick and Berlayne Smith with assistance from Emani Simpson and Jose Vasquesz meld their considerable abilities to sustain a sense of time and place. Director Alexander Harrington brings his decades of experience in classic theater to this new work, and approaches the drama with a well-paced sense of the material and the actors' energies.

The characters in this drama are the great German philosophers of the 20th century and it is the roads they took in the face of Nazism's victory in Germany that defines the perimeters of both our drama and the lives of the characters.

As Americans it is easy to forget that Germany for at least a century prior to the rise of Hitler was a country which was a center of the sciences and philosophy and that these greats included many Jews. Jews and Jewish thought and contribution to the arts and sciences was an accepted and integral part of the German zeitgeist. The shock of the rise of Nazism for Germans and particularly for German intellectuals was the incomprehensibility of such senseless violence happening in Germany. Americans today see our country as incapable of socio-political collapse because of the strength of our democratic traditions. Many Germans saw the Nazi's as a ludicrous ultra-nationalism and not a serious threat to the fundamental premises of society. Other apologists for the Nazism's aims saw its ultra-nationalism as a meaningful reaction to the defeat in WWI.

The audience shares the experience as the students of Martin Heidegger (Joris Stuyck) did when Heidegger expounded on the essence of being. At Davos he debated Ernst Cassier (Stan Buturla) on Kant and ultimately as he publicly spoke in favor of the Nazi Party. Heidegger's betrayed the true roots of his own philosophical premises, his teachers, his colleagues and not least of all of the love of his life Hannah Arendt. (Alyssa Simon)

This is a love story. We share Hannah's youthful enthusiasms, the breadth of her intellectual potential as her admiration and infatuation for her professor becomes a passion and his enchantment with her prowess becomes obsession. The interlacing of the moving poetry of Heine and Rilke as well as the music of Bach and Schumann color the texture of their emotions. Theirs is both an intellectual and emotional relationship.

As Hannah matures both as a scholar and a woman, Martin makes the choice to stay with his wealthy and politically connected wife Elfride (Alexandra O'Daly), rather than follow the call of his soul. Their lives separate. She marries. He moves forward in his profession. This story is a love story which has happened countless times, and yet his betrayal of his beloved mirrors the profundity of the Heidegger's political, spiritual and intellectual betrayals. It is a most extraordinary love story. The realities of the times are ever present in the lives.

Heidegger joins the Nazi Party to gain the rector-ship at Freiburg University. She is arrested and placed in the internment camp at Gurs. (She later escaped to the US through France.) The personal is writ large on the political canvas.

Stuyck, Buturla, and Simon gracefully bridge this line between the personal and the political as we move to the post-war years and the turbulent challenges of the creation of the state of Israel. Hanna Arendt now a professor of philosophy at the New School in New York was an ardent Zionist. She had been an early activist for the establishment of a Jewish homeland, a view that was not shared by those traditionalist Jewish scholars like Cassier, who saw the concept of state as in itself incapable of defining being.

Controversy followed Hannah Arendt when in 1961 she covered the trial of Adolf Eichmann for the New Yorker magazine. In coining the phrase “banality of evil' she incurred the wrath of many who felt that she was minimizing the monstrous evil that Eichmann had coordinated. The banality that Arendt examined was not the indescribable criminality of his actions. Rather she condemned the petty bureaucratic value system that sustained his psyche.

For philosophy enthusiasts, we thus return to Kant and the nature of self, morality and being.

Yet this is a love story, and Hanna Arendt and Martin Heidegger meet again-- and resume an intellectual relationship. Lackey does not provide us with reasons, but with feelings. The weaknesses of the man are petty. They entail a desire for fame and fortune, for admiration and status. Arendt recognizes this in him. We are asked to wonder about the consequences of self-serving decisions.