Sargent’s Watercolors at the MFA

Glorious Glitz Awash Until January 20

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 19, 2013

John Singer Sargent Watercolors

Curated by Erica Hirshler of the MFA and Teresa Carbone of the Brooklyn Museum

Opened at the Brooklyn Museum

MFA from October 8 to January 20

Museum of Fine Arts Houston, March 2 through May 26

Proper Bostonians never seem to get enough of the renowned society portrait painter John Singer Sargent (1856-1925). Now and then the tedious but lucrative task of recording the patrician features of American robber barons and their families or European aristocrats transcended paid commissions as enduring character studies and masterpieces.

His “Madam X” caused a scandal that ended his career in Paris.

It endures, arguably, as his most galvanic canvas. Virginie Avegno (1859–1915) was born in Louisiana, the daughter of Major Anatole Avegno of New Orleans, a gentleman whose family had emigrated from Camogli, Italy, and Marie Virginie de Ternant of Parlange Plantation, Louisiana. After Major Avegno died of wounds suffered at the Battle of Shiloh, Mrs. Avegno took her daughters to Paris. There Virginie became a celebrated beauty and married Pierre Gautreau, a Parisian banker. The portrait was shown in the Paris Salon of 1884.

In another era her face and hauteur might have launched a thousand ships.

Compared to that controversial portrait his iconic “Daughters of Edward D. Boit” captures the utter charm of four very different daughters.

It was Boit, a fellow artist and friend, who convinced Sargent to exhibit a suite of watercolors in a commercial gallery in 1909. He had painted watercolors since childhood but never considered the work to be a part of his commercial practice.

Sargent offered to sell them but only as a group. The entire exhibition was purchased by the Brooklyn Museum for just shy of $20,000. The MFA offered too little too late. The success of the first sale, however, inspired a second exhibition of larger and more finished works in December of 1911. This lot was pounced on by the MFA.

For the traveling exhibition of 92 watercolors, augmented with a selection of his paintings, the collections of Brooklyn and the MFA are being exhibited together for the first time. The project is augmented with works by Boit and others of Sargent’s circle. It is interesting to compare his work to the meticulous, detailed watercolors of the art critic John Ruskin.

Like Claude Monet, who died a year later in 1926, they were artist whose fame and accomplishments belong to the 19th century. By then it was almost two decades since the emergence of Cubism in 1907.

That Sargent was over the hill and out of the loop, but still fashionable in 1911, matters little to visitors who will be enthralled by the glib and masterful bravura brushstrokes of a brilliant if not particularly innovative artist.

Once he achieved wealth and status he strove to be free of the “burden” of portraiture. He aspired to be regarded as an artist in the greater sense. Toward that end two of his three mural cycles, for the MFA and Boston Public Library, were executed in Boston. It provided the opportunity to linger in Boston setting up a studio in the Fenway Palace of his great friend Mrs. Gardner who was by then a widow. That didn’t prevent gossip about their relationship. They shouldn’t have bothered as eventually he was outed by art historian Trevor Fairbrother.

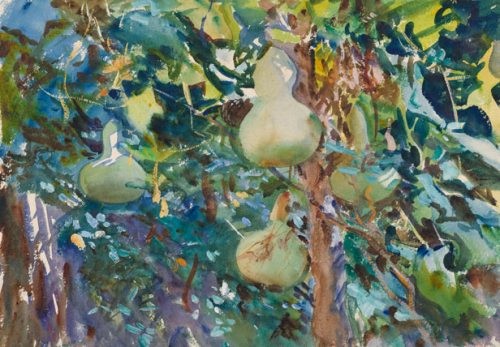

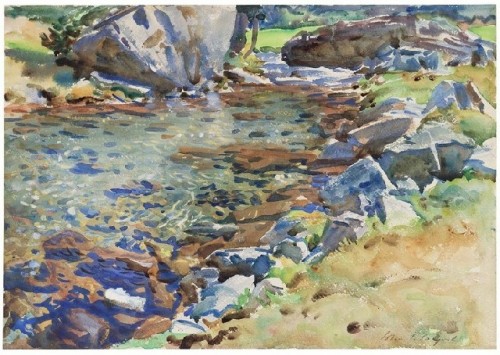

At his best in the portraits Sargent was notable for a juicy, fluid, bravura brush stroke particularly in defining the sheen of silk and folds of fabric. This technique is featured to full advantage in the watercolors. One is entranced by the speed and accuracy of his richly brilliant touch and attack.

As a medium watercolor is notoriously unforgiving allowing for no mistakes. One must approach the tooth of a spectacular sheet of textured paper with utter confidence. It is why, by comparison, the works on view by Boit and Ruskin seem so plodding and tedious.

This exhibition provides a fresh take on the artist through a total immersion in his mastery of a medium which we rarely see in such depth. Works on paper, particularly watercolors, are sensitive to light. These remarkable works have been kept in the dark. Today they are as fresh and stunning as when first shown just a bit more than a century ago. After this triumphant museum tour it is assumed that will return to the dark pulled out now and then to be viewed on request.

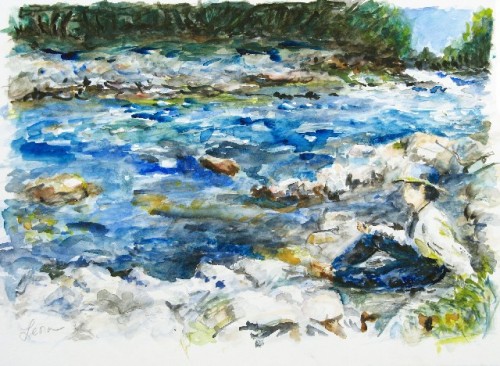

In the essays that accompany the exhibition it is stated that in the Brooklyn series the artist was painting for his own satisfaction. As a global traveler they are something of a diary of sketches. The later Boston works were more finished and meant to be displayed and sold. The assumption is that the Brooklyn works are more spontaneous and casual compared to the more deliberate Boston series.

It is difficult to see that as the works have been organized thematically rather than chronologically. While it makes for a more enjoyable grouping it also impedes the scholarly process of tracking his experimentation and development of the medium.

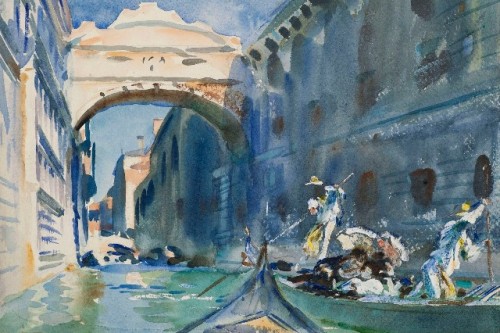

We do, however, get to absorb his fascination with Venice. With some 150 extant sheets it is the subject he depicted most abundantly. The oil paintings that he created of the City of Light are generally interiors or views of narrow calles. Prior to this exhibition we wondered why he, like Turner or Whistler, was not more inspired by the lagoons.

Now we discover that he explored the exotic combinations of tides and architecture in stunning depth. None of these images are Canaletto postcards. His view is often odd and askew. One of my favorites was the dark arc of the underside of a bridge (“Venice: Under the Rialto Bridge”). It tells me something quite wonderful about how Sargent viewed and loved Venice.

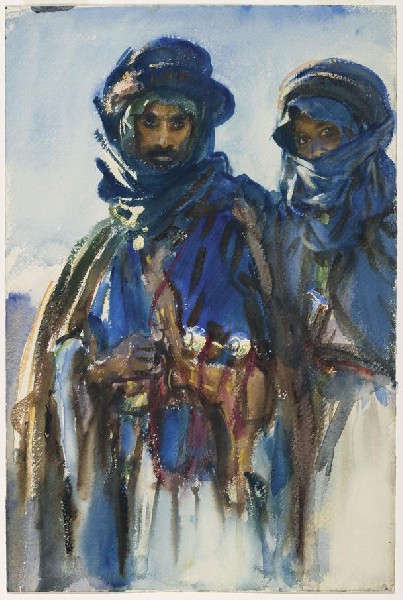

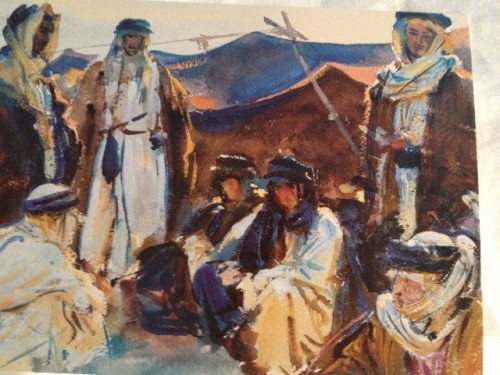

As research for the BPL murals and their overview of world religions he traveled in the Levant and Middle East. There are riveting studies of Bedouins with searing gazes. A particularly powerful one studies the light surrounding a mother and child. Her face is a blur set in shadow.

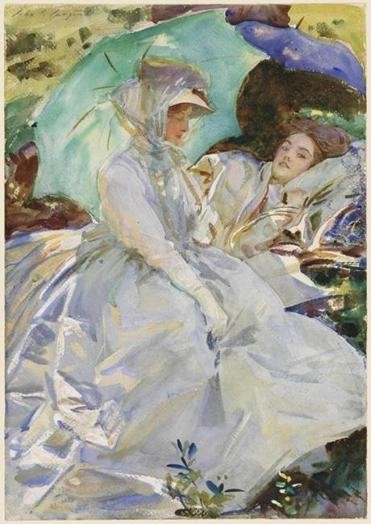

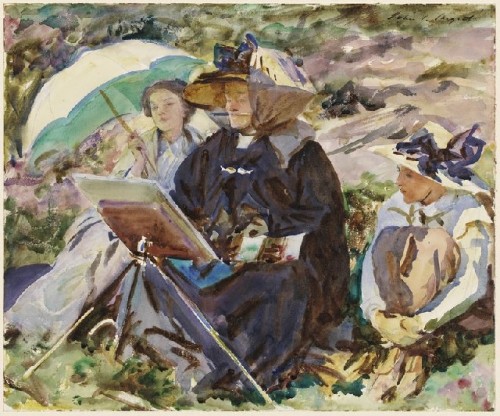

While by then Sargent had largely retired from the portrait trade he continued to paint people who were of interest to him. One of the strongest works in the exhibition is a study of an anonymous "Tramp." As pr for the exhibition “Simplon Pass: Reading” has been featured. It is a charming image of two women of leisure set in nature. Perhaps it was selected for reflecting the familiar trope of Sargent the portrait painter.

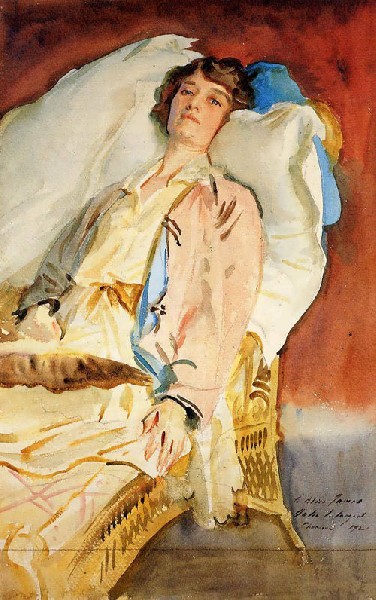

Of far greater interest is a psychologically revealing portrait of Alice Runnels James (Mrs. William James). Her long vertical frame tilts to one side leaning back in the pictorial space. Literally, she retreats from the viewer in a pose that suggests withdrawal, and from wall label information, chronic illness. This view of a fragile friend reveals depth and empathy rarely encountered in the official society portraits. His portrait of “Mrs. Jack,” which her husband found embarrassing, also reveals what was possible when the sitter was more than an acquaintance.

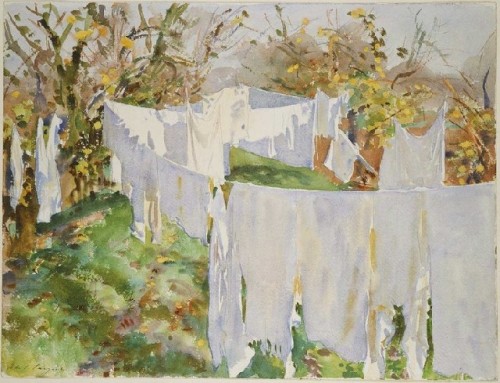

A great asset and challenge of the medium is the use of white. There is the natural white of the unpainted support. Delicate washes allow for transparency. There is also the option of highlighting and accenting over painted areas with the use of thick, opaque flourishes of gouache. This is sometimes done with impasto. It was a technique which Sargent mastered in his oil paintings and translates perfectly to a more fluid medium.

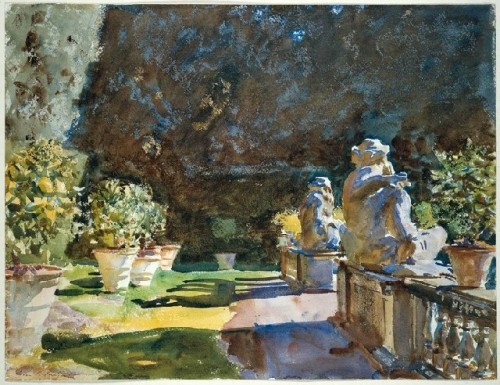

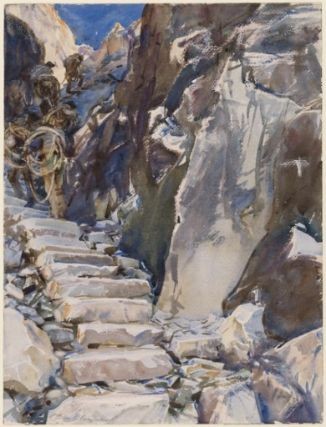

This approach is displayed brilliantly in fascinating views of the quarries of Carrara with enormous blocks of white marble. He also rose to the challenges of depicting a mundane view of laundry sheets hung out to dry or the furl of a sail. There are many variations of the range of endless possibilities. Consider for example a fountain “In a Medici Villa” or a view of a tower in “Venice: La Dogana.” The simple whitewashed geometry of “Corfu: Lights and Shadows” makes one think of Cezanne’s similar use of the cube, cone and cylinder at roughly the same time.

Ultimately, this rare and sumptuous exhibition makes us reconsider the range and depth of the artist. This different, more intimate view of a glib society portrait painter suggests that, in addition to a great eye and fluid touch, Sargent had a heart and soul.

Like the novels of Henry James it’s a tough slog to get under the skin of Sargent and the buttoned up ladies and gentlemen of the Gilded Age. If you have the time and patience it can be a good read.