Sargent as Court Painter to the Gilded Age

Reflections on MFA's 1999 Exhibition

By: Martin Mugar - Oct 20, 2013

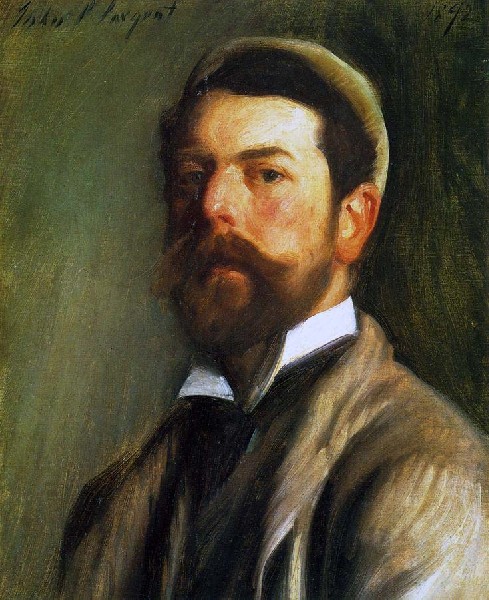

To the painting enthusiast, professional or amateur, who admires the techniques of realism, the matching of flesh tone, the verisimilitude of satin, the glisten of a moist eye, John Singer Sargent provides a sumptuous visual feast.

Painting in the stylistic tradition of Velasquez with its direct evocation of human presence, he shares in the bravura brushwork, the love of chiaroscuro, surface and texture that typifies Velasquez's painting. Most importantly he shares an affinity for similar subject matter: Both painted the rich and famous of their day. Ultimately it is the sociology of Sargent's work that intrigues this viewer.

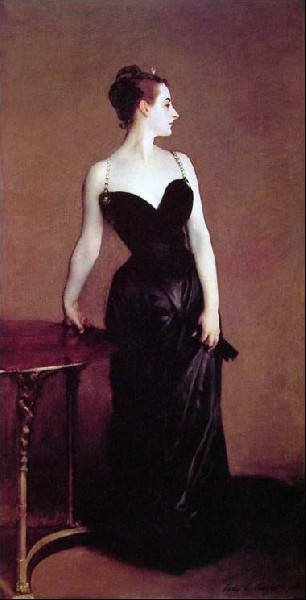

In the comprehensive exhibit of Sargent's work at the Boston MFA (1999) I imagined that I was viewing stills from PBS's Masterpiece Theater or a Merchant Ivory Production. Year in and year out his portraits satisfy some insatiable appetite in the American viewer to peer into the lives of upper class Europeans of the Belle Époque.

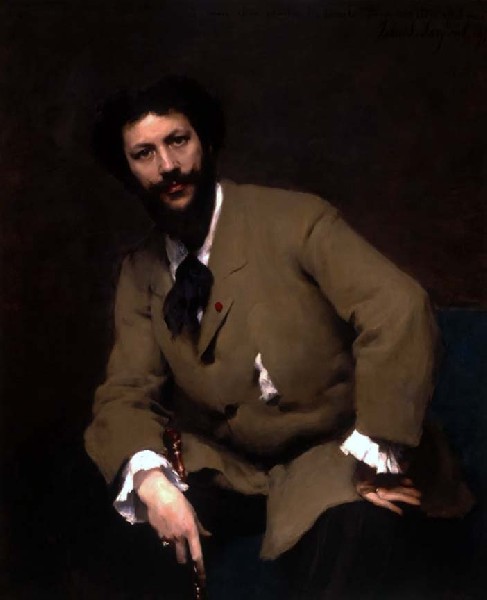

It's all there: the arrogant gaze of the powerful, the smug gestures of people who seem to pursue a life of perpetual leisure, the languorous gazes of desiring and desirable young women. Self- sufficiency radiates from their gaze and signs of wealth from the elegance of their clothing and surroundings. In a world prior to mass media, the medium by which you displayed status was how you carried yourself and what you wore. It was immediate, to the point and incontrovertible. Sargent's cast of characters act out powerfully these moments of self- display.

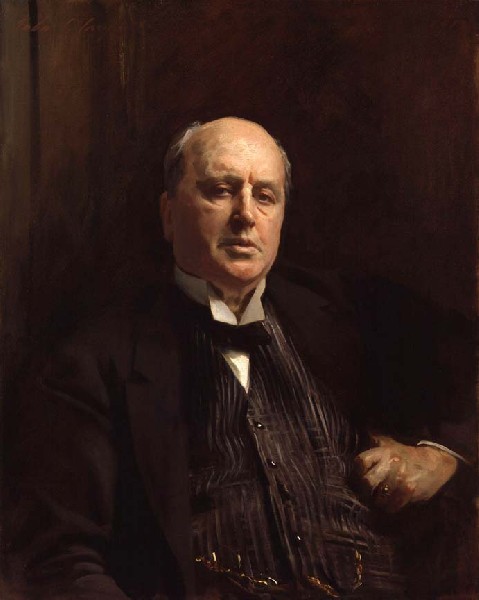

The rich and famous that Sargent painted were on the top of the social heap as was the court of King Philip that Velasquez painted. Whereas the courtiers of King Philip were in no doubt about their standing in the universe, the people of his world are actors, playing at being a king or assuming the airs of a corrupt and decadent European cardinal (in the case of the gynecologist dressed in scarlet) and know they have to act their part well if the public is to be convinced.

A kind of aestheticism pervades their poses. They can at times appear to be pretentious. Something you would never say of Philip the 1st. He doesn't have to pretend. The huge fortunes of the Gilded Age have raised these select few to the top but in the boom and bust economy of that era their position in the world is no divine right.

Sargent's paintings are a kind of documentary of the Transatlantic Bourgeoisie of the late 19th century (he stopped doing portraits in 1907), but the work has something of the puff piece. He has no desire to deflate their self -image as Goya was able to do for the Spanish Royalty. He gives them what they wanted. This acceptance of the values of the subject seems to have a regressive affect on his stylistic development. Sargent does not grow as an artist, either technically or spiritually.

The "Daughters of Edward D. Boit" is a painting he never surpassed in any way. Technically there is everything that you'd find in his later work and something that the later work doesn't have, a certain success at making the viewer conscious that the image is an illusion. This effect is in part due to a majority of the image being in obscurity, its references to “Las Meninas” which is itself a profound meditation on seeing and reality, and a simplicity to the mark making. Of course to be told by the portraitist that you are nothing but a figment of the artist’s imagination is not what you paid the artist to do.

I keep thinking of Alice Neel's models whose clothes hang on their bodies. They slouch, and drape themselves across the sparse furniture. Some sitters are fatigued, others angst ridden.... but all very mortal. Sargent is taking his social models from the past, as did so many artists of that period, but this posing is just a mask, a cover up that allows them to hide their mortality. It was the Pre Raphaelites archaism that ruled the day in England. Although on the one hand Sargent's sitters are very real, because of Sargent's technical abilities, on the other hand they are a cast of characters derived from Shakespeare's lords and ladies.

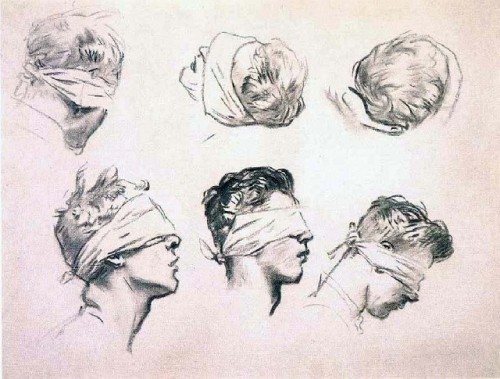

The final mural (of three projects two in Boston and one in London) of soldiers blinded by mustard gas in the World War is an unlikely statement from an artist for whom the indulgence of observing pleasurable scenery was the core of his visual language. He did confront the horror of it all and the result is an image that is emblematic of the end of an era. Painted in dark tones, the soldiers are rendered undifferentiated by their bandages which mask their faces and uniforms. The landscape is war torn and desolate. Gone is the world of wit and play, of garden parties or sunlit Italian vacations. The subtleties of moods or the assumption of theatrical poses is effaced by the horror of mass annihilation. The 20th century is there with all its uniformity and scouring of individual particularities

I suppose one could pursue the tack that Sargent and his sitter are out of touch with reality. The mass movement of WW1 and the revolution of the working classes would wipe the smugness from the faces of the rich. Stylistically, the art of the 20th century would show the traces of effort, labor and science.

The agonic posing and strutting, the exquisiteness of the sentiment of exquisite moments of that Bourgeoisie cannot be duplicated today. That world recedes further back in time to an art that describes it so perfectly and cannot be dismissed. No matter how much one might find his work suffering from a kind of false-consciousness, I cannot help but feel a pang of regret that this world, which, in the hands of Sargent is rendered so palpable and seemingly present, is forever gone.

Reposted from Art Deal magzine.