Drawing and Painting By Martin G. Mugar

Lesson Plans for Faculty and Students

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 22, 2019

Drawing and Painting

By Martin G. Mugar

54 pages, illustrated

$25.00

Available at Amazon

Having completed the undergraduate program at Yale University the artist, Martin Mugar, then stayed on to earn an MFA.

The program was revised and enhanced when former Bauhaus artist, Josef Albers, took over as director. The program developed into one of the foremost in American higher education. He attracted faculty, like visiting artist Willem de Kooning, who espoused different but provocative ideas, approaches and dialectical values.

Yale has morphed and changed over the years while keeping its formidable cutting edge status. It retains stability with a base in fundamentals as well as variables that reflect the ebb and flow of trends in contemporary art.

Compared to which Mugar, then as a student, and now as an abstract painter with an emphasis on color and exotic surfaces, has continued to draw outside the lines. It is better said, perhaps, that he was a maverick by drawing inside the lines.

His new book, Drawing and Painting, discusses some of that pedagogical tension. He drew from but was in conflict with artist professors like the abstract painter Al Held. Representing a then progressive position Held was befuddled that his student was making still life drawings and paintings. Mugar, however, chronicles just what he learned in that give and take.

While Mugar aspired to be a professional artist there was an aspect of him deeply rooted in the intellect of Yale. Of all of my artist colleagues Martin, by far, is the most well read and deeply philosophical. Others I know espouse theories but mostly in the aspect of muddled sophistry.

By comparison Mugar knows what he is talking about. It’s often challenging to read and follow his thinking process. You may not be up to speed with Kant (the domain of artist Adrian Piper) or Martin Heidegger but I try to hang tough and catch the drift. It is always worth the sweat equity. In fact I have been publisher/ editor for many of his provocative essays. They have a niche but devoted audience.

A constant in his writing is the theme of the sad state of contemporary art and how that corrupted education. In general I agree but not in details. Unlike Mugar, I do not hold to the idea that contemporary art was derailed by the conceptualism of Marcel Duchamp. Rather, I posit that ultimately Duchamp is the only modernist who has survived and indeed was critical to the development of post modernism.

Other than as historical phenomena modern masters like Picasso, Matisse, and Mondrian are not essential to the deconstructionists that dominate instruction in art schools.

But they are crucial to the critical analysis and lesson plans on drawing and painting that are the mandate of this slim and well illustrated book. It should be a useful guide to both fine arts professors and their students. In that sense it is among the more essentialist publications in a tradition that stems from Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook. That Bauhaus derived book was introduced to me in a freshman design class by the late Arthur Polonsky. It was the text reference for his unique, insightful and memorable classes. Then mostly a tabula rasa he filled my blank pages with ideas that have informed me ever since.

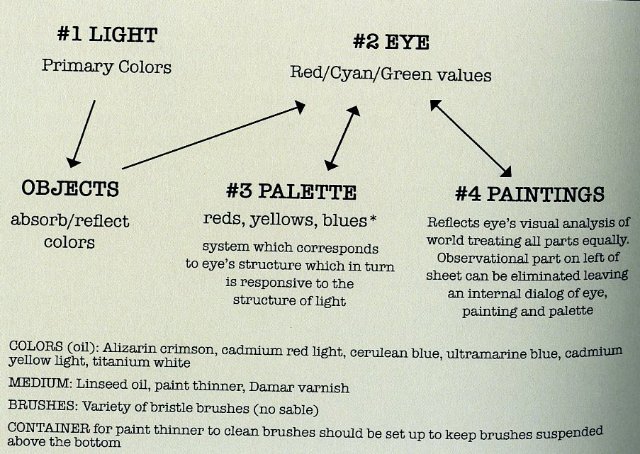

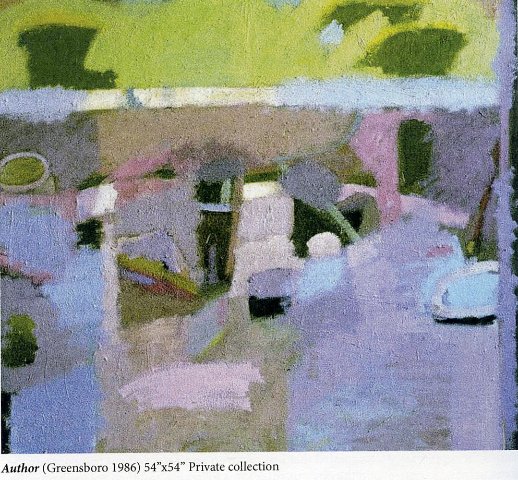

I posit that Mugar’s book, given a chance and some circulation, may well serve in a similar capacity. It is the summation and distillation of what he learned at Yale and then refined during many years of teaching. He is also judicious in quoting sources. It is interesting, for example, to break down the building blocks of how he came to set the colors of his palette. He is a master colorist creating paintings so delicious and enticing that you want to lick them.

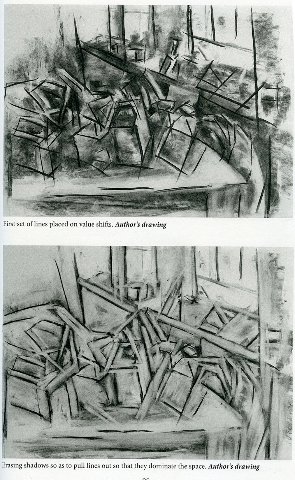

While a slim volume it was no doubt expensive to self publish. There are a number of color reproductions of artists he discusses. Most interesting are numerous illustrations of his demonstration works as well as example of those executed by students.

In my undergraduate art classes, be they drawing, painting, or sculpture, we worked from a model and the instructor circulated among us stopping to make the occasional comment.

The lesson plan that Mugar spells out is far more didactic. There is a specific agenda and way of seeing for each project. It is not the norm currently in art school to be told exactly what to do. Today the emphasis is on learning how to talk and write about the work.

Curators considering new work or jurying exhibitions are known to read submitted statements and make decisions accordingly rather than looking at the work.

The mantra that “my work speaks for itself” no longer cuts it.

The maximum entropy of that was experienced during a recent visit to a contemporary art exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums.

“Crossing Lines, Constructing Home investigates two parallel ideas: national, political, and cultural conceptions of boundaries and borders; and the evolving hybrid spaces, identities, languages, and beliefs created by the movement of peoples… Rather than aiming for an encyclopedic approach to the topic, the curators have sought to frame this metaphoric intervention through a range of experiences and geographies, all while staying focused on historical specificity and individual experience.”

Viewing the actual work there was no there there. We were mostly befuddled. To grasp the work it was essential to read the extensive wall texts. After some due diligence the net impact was why bother.

Surely Harvard’s curators are wicked smart. But trying to comprehend the work was my dumb luck.

This is what Martin has saying in all of his essays and now a book. On that we totally agree. Even museums themselves, like the renovated MoMA, and ubiquitous social justice wall labels, are exercises in deconstruction.

For rigid reactionaries a Monet is still a Monet is a Monet. But you just might find it in a gallery dedicated to French colonialism and post Napoleonic imperialism.