Dishwasher Dialogues James Baldwin

Baby I Was Never American

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Oct 22, 2025

Names and Nightmares

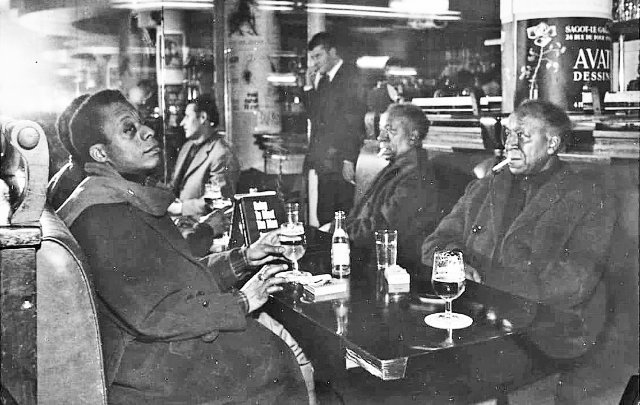

Rafael: As far as money goes, Chez Haynes wasn’t cheap, and the ‘names’ who frequented the restaurant were well off. One of these names was the writer James Baldwin who often came into the restaurant at a quarter to two in the morning, just before we closed. He was a pal of Leroy, who had also known the writer and poet Richard Wright who had died in Paris under murky circumstances. Baldwin sometimes arrived late at night, with the African American painter Beauford Delaney. We, the staff, were supposed to go home at two. We were all tired. But Leroy knew we would stay as long as necessary for Baldwin.

Greg: He didn’t need to insist too hard. Staying open for Baldwin was never a chore.

Rafael: You’re right. Baldwin was a great man.

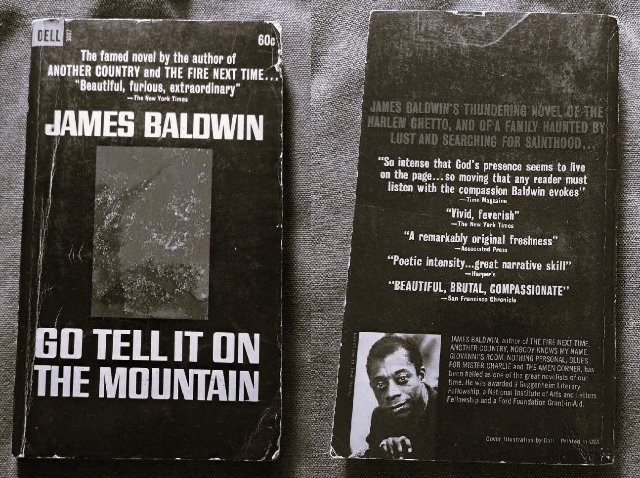

Greg: I knew of him from a book I read in high school English class—Go Tell it on the Mountain. But at that time, I didn’t get the significance. It was just another book, like Othello, which I had to read. I don’t know if they were for the same class, I just know I read them. But in university, before I came to Paris, Baldwin’s name often came up in late night conversations and/or at Anti-Vietnam and Civil Rights gatherings.

So, he was a ‘name’. Even a ‘star’, but I do not remember anyone talking about him like that. That would have been too flimsy a descriptor. Not that Chez Haynes didn’t attract its share of celebrities and so-called ‘stars’ of the day: Paloma Picasso, Jacques Dutronc, Isabelle Adjani, Johnny Hallyday.

Rafael: Oh yes, I remember Paloma, she used to come in with her boyfriend and she always paid by check, so I knew her address in Neuilly. I never asked her if she spoke Spanish. I never even told her I admired her father. I was struck by her stark beauty. What could I say? Flirt with her in Spanish?

Greg: James Baldwin was in a different league entirely. It was as if Sartre or Beckett had walked in. Which neither ever did; not in the four years I haunted the place. But Baldwin did. Sartre died near the end of my time in Paris. There was a huge turnout for his funeral. So maybe he had an excuse. But Beckett lived on for another ten years––no excuse.

I remember Baldwin being rather relaxed and cool. The epitome of ‘cool’. That kind of cool that is laced through and through with brilliance. You must remember when I first saw him, I was just the kid in the back. I didn’t even know he was there for an hour. I was cleaning out the sink or tidying up the salad station, wiping down the espresso machine. Then I was called out of the kitchen for a few minutes to fetch something from the bar. The restaurant was almost empty but suddenly it was host to an amazing seminar––and for a moment I got to slow walk through it and listen to James Baldwin up close say words, any words. His voice was enough itself.

Rafael: Sometimes one of the waitresses, Sophia, if I remember right, brought some cocaine, and we would snort up in the WC. Full of energy, the staff would now be turbo-charged, attending to Baldwin and Beauford quickly and efficiently. Baldwin would complement Leroy on the service and how energetic the staff were so late at night. Leroy may have suspected something, and now that I think back, I’m sure he knew that we were on some good high suddenly. There was a twinkle in his eye as he kidded Baldwin, telling him that the staff, all aspiring artists of one kind or another, admired him. And we did. He was unpretentious, something so rare among successful creative people. Especially painters––they were the worst in their boasts and incessant bragging about their own shows and their name-dropping was sickening.

Greg: That kind of ‘big-boast-small-talk’ used to drive you crazy, especially at an art show: yours, theirs, whosever. The talk became ridiculous. It betrayed a particular poverty of thinking that all communities are prey to. Especially those where self-identity as artist or writer was still precarious. You would seethe, then suddenly announce you were bored (your favorite word when you were annoyed and uneasy) and leave. It is amazing the depth of emotion which the words of peers can elicit. I wish I could say I was immune. But none of us are. I tend to respond with foolish jokes.

Rafael: Responding with a joke is smart. Baldwin and Beauford would invite Leroy to sit with them, and they’d shoot the breeze for a while. They’d invite him to a drink or two.

Greg: They shared a common community. Sitting around the pink clothed tables of the restaurant late into the night. I envied them that. But they also shared a common nightmare. It’s no wonder Leroy drank.

Rafael: Leroy smoked weed too and hash once in a while, and he could afford as much cocaine as he wanted, but Leroy’s high of predilection was scotch and could he put it away. I knew because as the bartender, I not only brought up the wine bottles and the beer cases from the cave, but I also replenished the hard stuff. Every evening when I got to work, I refilled near-empty bottles on the mirror shelves behind the bar. I knew how full the bottles had been when I had left the bar the previous evening. The only person who had access to the liquor was Leroy. It was quite shocking the amount of scotch Leroy drank after hours.

Greg: That moment behind the bar at the beginning of the night would frequently signal what kind of night it would be. When I finally took over the bar full time, apart from the single malts, I remember there being three bottles of whisky lined up together on that mirrored shelf. A bottle of J&B, a bottle of Ballantine’s and a bottle of Johnnie Walker Red. At the end of the night, when we closed up, they were still mostly full. We filled them up regularly. I can’t remember which one Leroy started with, but the next evening would usually begin by me letting the waitresses know if it was a one, two or three bottle night we were facing. If it was the latter, we often didn’t see him, so those nights were a crapshoot. To give Leroy his due, on many nights (and there were many) there was no whisky missing. It was an on-going war he was in; one he knew all too well, and some days the battles were won and other days they were not.

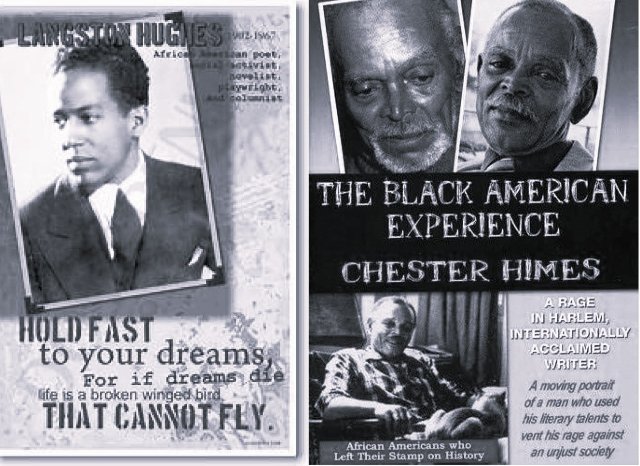

Rafael: When he’d see me bringing up the new bottles, he’d say ‘hey Rafael, who the hell is drinking my liquor? You guys drinking on the job or what?’ Toward the end of the evening when he was good and loose, he’d talk about the African American writers and poets, and Langston Hughes and Chester Himes.

Greg: Those were insights which the bottle brought us care of Leroy. He paid the price of admission for all of us. Sometimes the price was darker and unexpected. Even on his drinking nights he could give a sharp and sober critique of America. The amusing incident, the funny remark on growing up in the U.S. turned sour. A whisky sour of a different kind. Crude, angry, bitter. One of the American waitresses once asked him how he could be so hard on his own country. ‘You’re American’, she said. His eyes flashed and he just said, ‘Baby, I was never American’, and he walked back into the kitchen. We all knew what he meant. Even if we didn’t know. Even if we didn’t have the faintest idea of what it was like, what it truly felt like.

Rafael: He told us he was writing a book about the black experience in Berlin during the war. He mentioned this oeuvre quite a few times. I found it intriguing, to say the least. We knew he’d been in Berlin after WWII, he knew the German capital, and I think his heart went out to the few blacks who had been caught in the Nazi horrors and had survived. I asked myself why he never asked Baldwin for help in getting the book published. Africans trapped in the Hitlerian hellish maelstrom were a tragic subject. The Africans in Berlin were referred to in later years as the Rhineland Bastards. German soldiers had been in Angola, when it was a German colony, until 1914, they had children with the local women and some of the offspring came to Germany.

Greg: I don’t think he ever finished the book. I am not sure he wanted to. I remember him showing me some of the pages one day. They were good. He clearly had testimony to give and a story to tell. But it was a hard story to tell. He alluded to it sometimes, but not in much detail. I do remember one slow night back at the salad station he told me he had started a PhD after college. He was sitting on his chair peeling onions or potatoes. I think he said the PhD was in sociology. Early in the process he went back to the small town where he had been raised—in Kentucky I think—to research the local archives the year he was born. At that time, he said, they listed the town population as ‘635 people and 847 cows, pigs and n****rs.’ I am guessing here at the numbers. He may also have been guessing when he told me. But that, of course, was not the point. ‘I was lumped in the second group’, he said quietly, never looking up from the bucket of peels. I am assuming it was sometime afterwards that he joined the American army. Then he went to war. After it ended, he never went back. Despite all the stories about his life, he was rarely forthcoming about the overt racism that asphyxiated his existence. Not to us. It would have been good to read more pages. It would not have been an easy read. Clearly it was not an easy write.

Rafael: Once I went to Leroy’s apartment to get some papers, and there in his living room, I saw ten chapters nailed to the wail, not stapled or in folders; no, he had driven a three-inch nail through the pages of each chapter as if to emphasize the brutality of that era. I couldn’t help thinking of the spikes smashed into the twisted, deformed hands of Christ in Grünewald’s Crucifixion rétable in Colmar in France. At the time, I had only seen the painting in reproduction. Years later, I drove to Colmar and looked at that stunning work, and my mind went back to Leroy’s book and the chapters nailed to the wall.

After he died, his belongings disappeared, there were rumors that the novel was going to be published, but nothing ever came of it. I don’t even know if the pages still exist. Maybe Leroy destroyed them. It was the kind of thing he might do. I also think at times that the U.S. government made sure some of his things disappeared. Leroy had been in army intelligence after all. He said it himself more than once. You don’t fuck with the Internal Revenue Service and you sure as hell don’t fuck with the U.S. Army.