Machinal by Sophie Treadwell at Williamstheatre

Avant-garde Production of Expressionist Drama

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 25, 2008

Machinal

By Sophie Treadwell (1928)

Directed by Robert Baker-White; Scenic design by David Evans Morris; Costume design, Deborah A. Brothers; Lighting design, Julie Seitel; Sound design, Eric Kang. The Company: Lydia Barrett-Mulligan, Nathaniel Basch-Gould, Mirabel Bradley, Augusta Caso, Jordan Dallas, Meghan Rose Donnelly, Peter Drivas, David Edwards, Lizzie Fox, Sara Harris, Amanda Keating, Dan Kohane, Evan Maltby, Tess McHugh, Michaela Morton, Nicholas Newmann-Chun, Noah Schechter, Lisa Sloan, Adam Stoner, Tyisha Turner. Williamstheater, The 62 Center, Williams College, Wiliamstown, Mass. Box office 413 597 2425 (Tues-Sat 1 pm to 5 pm) Performances Oct. 23, 24, 25, 30, 31 and Nov. 1.

Link to 62 Center at Williams College

Entering the theatre for a performance of the 1928, expressionist drama "Machinal" by Sophie Treadwell (1885-1970), we were directed upstairs and then down into the reconfigured black box, Center Stage. It took a moment to become reoriented to the generic cube which has been entirely reconfigured. We found seats to the side of the stage which had us leaning over and down for a view of the performance.

As the evening progressed attention was diverted to actions that were staged on multiple levels and angles all about us. During some sequences a projecting platform/ room was so close to us that the actors were within arm's reach. Even before the play began we marveled at the amazing set by David Evans Morris. In keeping with the feeling of the Mechanical Age evoked by the 1920s drama there were elaborate pipes running about with extensive copper tubing. This included the edges of the railings constructed for the special wings of seating. This sculptural, minimalist design was further augmented by the unique lighting fixtures and light design by Julie Seitel. Another important element of the ominous, crushingly mechanical aura of the drama was provided by the stark and compelling sound of Eric Kang. This conflated from oppressive to sensual during love sequences augmented by guitar and flute.

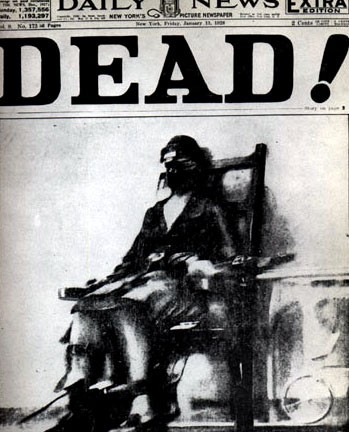

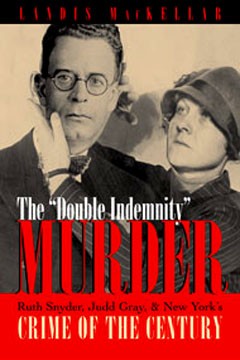

During its initial Broadway run the play was a hit loosely based on a ripped from the headlines story involving Ruth Snyder, a stenographer, who was convicted of murdering her former boss and husband. She and her lover, Judd Gray, were convicted in 1927 and sentenced to the Electric Chair in New York. A witness to her execution, Thomas Howard, had a concealed camera strapped to his leg. His photograph on the front page of the Daily News caused such a sensation that there was an additional press run of 750,000 copies. There were attempts to prosecute the photographer and publication but nothing came of it.

Given this factual basis, fresh in the mind of the audience of that time, the drama was less of a theatrical device than it appears today. In this remarkable student production at Williams College it is staged as a classic of avant-garde, expressionist theatre and for its emphasis on feminism.

With stunning effectiveness the opening scene, set in an office, was so clipped, robotic, and staccato that we anticipated an evening of abstracted images. We were intrigued by the unique designs of the work stations of stenographers and a woman operating a telephone switch board. Everything about the pace and environment was hostile and oppressive.

Into this environment enters the fragile and lovely worker Helen (Lizzie Fox). "You're late, as usual" is repeated by a chorus of her fellow workers. It seems the boss, George Jones (Evan Maltby), wants her on many levels. The other secretaries demand that she sort the mail while he orders her to come into his private office and take a letter. Helen is filled with fear of the implied intimacy. Particularly, when it leads to a marriage proposal.

In a scene with her mother (Lisa Sloan) she desperately seeks advice. The mother is of little help in the matter. For reasons, other than love, young ladies are meant to be married. But Helen is clearly not ready for a commitment. It is crucial that she does not love this man. Her wedding night is a disaster of submission. Followed by the harshly presented delivery of an unwanted baby. She refuses to nurse the infant girl. The sets, costumes (imaginatively designed by Deborah A. Brothers), and brittle acting style accent the horrors of her torment at being trapped into a role forced upon her by the conventions and expectations of society.

During the middle of the play, which runs without intermission for about 100 minutes, she meets and has an affair with a man, Richard Roe (Nathaniel Beach-Gould), who apparently killed two bandits that had held him captive in Mexico. He accomplished this by getting them drunk and then beating them on the head with the empty liquor bottle weighted with pebbles. This would later evolve to be the similar murder weapon used by Helen. Durin the initial mating scene with Richard the set went dark and action was enervatingly slow. It was a struggle to resist slumber. But the pace came alive again when she was arrested and put on trial.

The trial scene was handled brilliantly with the judge on a balcony looking down at the court. The prosecutor was conveyed with compelling force by Lydia Barnett Mulligan. The final execution scene entails a remarkably original device designed by Morris and lit by Seitel. It effectively transforms the execution from fact to grim fantasy. Yes, Helen took the life of her husband. His offense was that he was simply a husband. George was a kind of everyman of the mores of the period. Treadwell turns Helen into a feminist martyr of the institution of marriage. Helen is both criminal and oppressed victim. She killed and then dies for love.

Today, well, all of this is more complex. Not that anything is really different. Women still marry for security and position. But, arguably, with their eyes open. Today they have more options than Helen. So this play is something of an avant-garde chestnut and relic of feminism. But it was recreated with loving attention to detail at Williams. Most of the characters were superb if somewhat one dimensional. It is only Helen, in an amazing performance by a very gifted Lizzie Fox, who really grows and evolves as a character. To a lesser extent this is true of the husband in an outstanding performance by Evan Maltby.

In general the stylized, expressionist text left little for the actors to work with in fleshing out their characters and motives. While limiting it also placed fewer demands on young actors and was accordingly an apt choice for an ambitious production using a very large cast. Most of the actors played multiple roles.

Given the superb direction of Robert Baker-White, the technical aspects and performances of the company, it is incredible to realize that this was an undergraduate production. On every level it was a riveting evening of theatre which would surely hold its own Off Broadway. Bravo to all involved.