Ancient Nubia Now

Social Justice Catches Up with the MFA

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 25, 2019

Following a round the world honeymoon Mrs. Jack Gardner, a New York socialite, settled in Boston with trunks full of the latest Paris fashions. In one of those gowns, with then shocking décolletage, she was depicted in a full length portrait by John Singer Sargent. The painting caused a scandal and proper Boston women shunned her radical chic with the retort that “we have our hats.”

Sticking to conservative tradition, and the extreme of white privilege, Boston society has never embraced or even tolerated harbingers of reform and change. That was particularly true of established educational and cultural institutions like The Museum of Fine Arts.

There has been change in recent decades but incremental and less than enthusiastic. Recently, the MFA has been in the cross hairs of media and community outrage and scrutiny. Measured administrative responses to charges of racism have been enforced with aggressive reorganization, hiring, and programming.

The Boston Globe has been particularly harsh implying that the evident changes are knee jerk responses.

The review by Murray Whyte of a special exhibition Ancient Nubia Now, based on the museum’s vaunted permanent collection, reads more like a punishing, finger in your face editorial than an objective review.

“…the show is unflinching in its atonement. “Correcting the Story” is the title of an introductory text block near the show’s entrance, and the MFA means it. “Reisner’s prejudices led him to misinterpret his findings,” it reads, and that he “made a serious miscalculation.” To put a fine point on it, the museum makes clear that Reisner “had it almost entirely backward."

“Such outright penance right there on a museum wall is no small thing, and the museum should be given due credit. It admits it hasn’t given its Nubian collection much notice in years, but its sudden rediscovery is surely in step with the moment.”

In another recent piece by Whyte the lead reads “Maybe it’s just me, but the Museum of Fine Arts’ 150th anniversary next year is starting to feel as festive as a ritual of self-flagellation. Its grand announcement, convened last month for both press and the museum world alike, was a solemn affair; its plans, step by step, read as unvarnished repentance.”

That scathing column stated that it was Whyte's first anniversary of covering the fine arts for the paper of record. Perhaps we might regard his remarks as insensitive commentary and rookie mistakes.

Consider that major exhibitions like Ancient Nubia Now take years to develop. It results from decades of research and change in the field. It’s absurd to suggest that the exhibition represents a “sudden discovery” that is “in step with the moment.”

If in Whyte’s sensationalist purview the Nubia project is a hasty, knee jerk act of atonement the same might be said of another current special exhibition Hyman Bloom Masters of Life and Death. To be sure decades of institutional anti Semitism informed the systematic neglect of Bloom, Jack Levine, Karl Zerbe, David Aronson, Arthur Polonsky, Henry Schwartz and other leading artists of Jewish heritage. One might add the renowned Lebanese painter and poet, Kahil Gibran, and his sculptor nephew.

The sensational and stunning Bloom show, which we will review in depth at another time, has been on the MFA’s ‘to do list” for a long time. Curator Erica E. Hirshler has labored on it intensively for the past two and a half years. This project was in development long before the museum came under attack.

It has never been easy to be an art critic in Boston. It’s not just that the MFA and Boston's social and cultural leadership have been racist and anti Semitic. The deeper and more troubling fact is that the MFA, and to some extent the Institute of Contemporary Art, has been arrogantly indifferent to all of Boston’s established and emerging artists. That it took decades to recognize Bloom is the tip of the iceberg.

There were systemic, endemic, and existential conundrums. The ICA, for example, was established as a kunsthalle or exhibiting but non collecting institution. Absurdly, not wanting to overshadow or compete with the ICA was an excuse for the MFA to stay out of modern and contemporary art.

Under former director, Malcolm Rogers, he stated that the museum’s greatest commitment to Boston artists was the School of the Museum of Fine Arts.

With the appointment of Kenworth Moffett, and founding of a poor step sister department of 20th century art, the museum stumbled into collecting. As MFA curator Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. put it at the time (1970) “The MFA is getting into 20th century art now that it is almost over.”

The MFA established the sporadic Maud Morgan Prize to honor women. The ICA marginalized local artists into an off season summer slot with a mixed bag series of Boston Now exhibitions.

Fairly recently, the ICA decided to start a collection. The absurdity is that it’s award winning, jewel box, land locked building lacks space to display and store its acquisitions. Like the MFA, when market prices are out of reach, it comes to the game a day late and a dollar short.

As a world class, encyclopedic museum, however, like those Brahmin ladies who shunned Mrs. Gardner, the MFA “has its hats.”

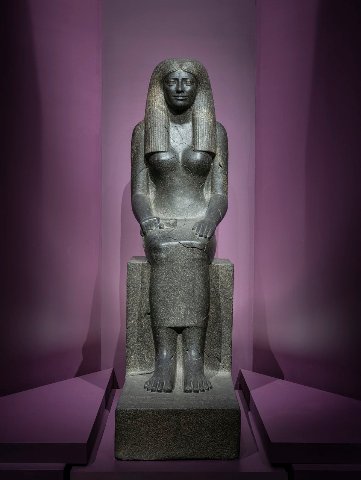

A demonstration of that depth is the sensational Nubia show. The astonishing fact is that most of the work on view has languished in the basement for roughly a century. An exception, however, is the Middle Kingdom, monumental sculpture The Lady Sennuwy. It was an Ancient Egyptian masterpiece looted and buried in a ancient Nubian grave. That occurred during a time when after 1,500 years of Egyptian occupation the kings of Kush conquered and ruled in Ancient Egypt. They comprised Dynasty 25 (of 30) during the Late Period prior to the Greek or Ptolemaic rulers the last of which was Queen Cleopatra.

The MFA has the finest collection of Old Kingdom Egyptian Art, second only to the Cairo Museum, through the brilliance, aggression, and good luck of George Andrew Reisner, Jr. (1867-1942). He headed one of four teams that excavated the pyramids of Giza. His dig around the pyramid of King Mycerinus yielded the greatest treasures.

Each year excavated objects were divided between the archeologists, representing their museums, and officials of the Egyptian government. Reisner proved to be particularly astute in this barter and trade. One coup was retaining the bust of Ankh Haf. As a true portrait it may be the rarest and finest treasure of Old Kingdom art.

While head of the museum’s Egyptian Department he remained in the field. Although keeping scientific records Reisner was always off to a new site. Crates were packed and sent home to fill a basement wing of the museum. One of those concessions was to excavate in what was ancient Kush and now generically Nubia or the Sudan.

In the racist views on Reisner's watch that was viewed as Black Africa and thus of lesser artistic and culture value than Lower Egypt. It is accurate to state that ignorance and racism account for why the work languished in storage. Many factors account for the total reversal which informs the insightful special exhibition.

Whyte quotes Reisner “The (Nubian) native negroid race had never developed either its trade or any industry worthy of mention, and owed their cultural position to the Egyptian immigrants and to the imported Egyptian civilization,” he wrote in a 1918 bulletin for the MFA, where he was a curator of Egyptian art.”

While Reisner remained in the field the MFA was staffed by his assistants. William Stevenson Smith wrote the standard history of Ancient Egyptian Art. Dows Dunham published the excavations of Kerma and Meroe.

It was emotionally overwhelming for me to view the Nubia exhibition. Truly it is a collection that I know from the ground up.

My first job after graduation from Brandeis University in 1963 was in the Egyptian Department of the MFA. I walked into the office and asked for a job. The department secretary threatened to call security. Dr. Smith instead asked me to sit and asked what I had in mind. After an elaborate process I was hired.

There were several weeks of orientation. That entailed tours of the collection with curators. One day Dr. Smith produced a ring of keys. In the basement he opened what proved to be a wing of the museum. It had been decades since anyone had been there.

“This is where you will work Charles” he said. The first task was to sweep and remove barrels of dirt. Then I asked for paint for the walls and floors. That was followed by dusting all of the objects. After each task I asked Dr. Smith to come and inspect.

Eventually, I was sent to the conservation lab and taught basic stone ware restoration. I was given permission to open crates. I got tables and spread out a vast array of shards. Through months of effort I found pieces that went together. Over time I restored a collection of Old Kingdom stone vessels. Missing areas were filled with plaster then sanded and finished. Blank areas were painted in a trompe l’oeil manner. Some pieces were displayed. I would point them out in later years to students during museum tours.

Now and then Dr. Dunham would visit to check on objects he was writing about. In this process he discovered a large, stone Horus sculpture that was restored and put on display.

During two and a half years in the basement I regarded myself as a servant of the pharaohs. Each morning I had coffee and threw the I Ching which I noted in a book. There were mummies near my desk. Their heart scarabs had been shucked. I repaired them with cutout paper hearts. It seemed the least I could do for time travelers languishing in the MFA's basement.

To get through long isolated hours I listened to the local soul station WILD.

One day I was surprised when a guard visited me. He said that Mr. Rathbone, then MFA director, asks if you can turn down the radio?

Later as a critic and journalist I interviewed Perry and every other director since then. Before the recent incident of racism I met with current director Matthew Teitelbaum. I knew him years earlier when he was a young curator at the ICA.

We talked about his considerable efforts to make First Nations people integral to the collections and programs of the Art Gallery of Ontario. We visited the museum in September and learned first hand the extensive social justice awareness of virtually all Canadian museums.

Similar plans for the MFA were touched on with Teitelbaum but there wasn’t enough time to explore in depth. Touring the Bloom show Hirshler stated that she had the complete support of the director. She was emphatic that if the MFA was going to take on such projects it would be done “the right way.”

To be sure there is much work to be done. Systemic change will not occur overnight or as a result of media pressure. It’s a daunting task and Teitelbaum may prove to be the right man at the right time.

As a Bostonian I grew up with the MFA. It’s in my DNA. Back off and let them do their job.

For now, the Nubia and Bloom exhibitions provide vivid and compelling evidence that the times they are a changing. The answer my friends is blowing in the wind.