Gil Shaham and David Michalek Translate Bach

Extraordinary Music and Visuals at Zankel Hall

By: Susan Hall - Oct 26, 2015

Bach Six Solos

Gil Shaham, Violin

Original Films by David Michalek

Zankel Hall

Carnegie Hall

New York, New York

October 25, 2015

Having attended William Kentridge’s illustration of Schubert’s Winterriese cycle sung by Mathias Goerne, the first image projected for the video accompaniment came as a shock. A small baby, lying on his back, seems to be listening to Bach, as Gil Shaham begins to play the first Sonata. The baby appears to be absorbed in the music, but then the camera pulls back to reveal a slightly older child and a mother. All of this is in extremely slow motion, the pace at which David Michalek often does his video portraits.

When violinist Shaham was about twelve he heard the first Bach solo violin Sonata for the first time and thought: what is this? Listening to the Partita that follows, he wondered at a violin playing chords, its cool sound. The solo instrument could sound like an organ and then an orchestra! He was swept up in the wonder that is Bach.

After fearfully resisting performance of the great solo violin pieces, Shaham took them up with incredibly detailed and thoughtful study, producing today a rendition for which there is no equal. He now plays with a Baroque bow, a built up bridge of Bach’s period and gut-core strings. His performance is clean, clear and precise.

Shaham says that the Baroque amendments make it easier for him to play faster and convey the excitement of the music. Shaham has exceptional musicality and yet maintains a warm presence.

His virtuosity sparkles like Michalek's drops of water catching light as they deconstruct a still life vase and then put it back together. Vibrato is thoughtfully applied. In a curious effect in one video, a hand trembles like the vibrato. Yet its feeling is effervescent and not at all heavy-handed.

If Shaham sweeps listeners in, Michalek is stilling them. Michalek offers birth to death images which glow like the music. Dances sound dance like in Bach. In the images, poses are frozen, or in extreme slow motion including allemandes, gavottes, gigues, minuets. We thought the projection of the video, which is cast on the stage above Shahan’s head was also in the prompter’s box. In fact it is.

When I suggested to Michalek in a brief post-concert talk that Shaham referenced the video in front of him in the prompter's box, he said absolutely not. If the video was not a stand in for a conductor, how did the video and the music sync? Michalek studied Shaham’s recorded performances of the Bach and learned his tempi. As lively and present as Shaham’s performance is, he apparently plays at the same speed each performance, having worked hard to determine it.

I wondered if the projectionist could alter the speed at which the images were being projected. No. The fade in and fade outs are controlled in the moment, but no other part of the video is.

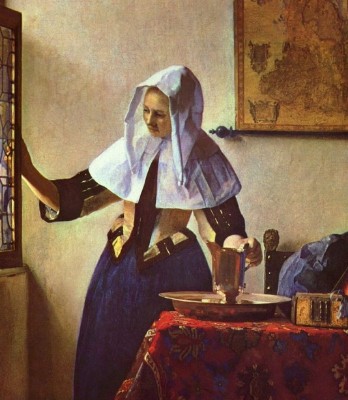

I asked Michalek if he would mind my calling a young girl in an abbreviated hoofdoek headpiece a 'Vermeer girl.' He laughed. All of Vermeer’s portraits are of subjects absorbed, even in a pitcher of water.

Absorption is Michalek’s idée fixe here. As Shaham is absorbed in Bach and makes us into active, absorbed listeners, so too the subject of the portraits before us are absorbed. The joy that is Bach and that Shaham expresses is beautifully rendered in a video of a Japanese woman holding two fans during a chaconne.

This was a fascinating evening in which Bach and Shaham were cast in a new light by images. Would the images perhaps work better if they were projected at the same level as the performer instead of being cast above him? All music being performed with images is a work in progress. How best to achieve these parallel universes or marriages is being worked out. Performers and symphonies across the globe are experimenting. Carnegie Hall does this to perfection.