Goodman Theatre Sings Pullman Porter Blues

Cheryl L. West's Brilliant Play is Soulful and Brimful of Pleasure

By: Susan Hall - Oct 27, 2013

Pullman Porter Blues

By Cheryl L. West

Directed by Chuck Smith

Chicago, Ill.

September 14 to October 27, 2013

Pullman Porter Blues is richly textured entertainment. But entertainment it surely is, first and foremost. The twelve songs appropriately plucked from the blues literature, with a little barbershop intermixed, thread through the show.

The emotional arc is clear from the start. ‘Women don’t take no shit.” Men have to learn how to follow suit.The men in this case are three generations of the Sykes family who end up working together as porters on the Panama Limited from Chicago to New Orleans the night of Joe Louis’ Heavyweight Championship win over James J. Braddock.

Just as the Louis victory was a game changer, so too is this trip. A grandfather’s support of the education of his grandson, and his own son’s effort to become a man by aiding A. Philip Randolph’s movement to unionize porters, smash and clash until the grandfather commits to the future union.

The women in the play are strong. E. Faye Butler in the iconic role of Sister Juba is a force of nature, as so many older black women had to be. In a scene that rivals the comment in Ice Cube’s Barbershop 'that all Rosa Parks needed was a rest', Sister Juba sings, after struggling to remove a stifling girdle, “Free, free at last.”

The generational mixing and matching echoes forward to the present as we struggle to find a comfortable place in our society for the young African-American male. The porter job is striking. George Pullman, who envisaged this occupation because slaves were used to being correctly servile, also provided a job that suited black man at the time. It got them out of the house, giving them a breather from their Sister Jubas.

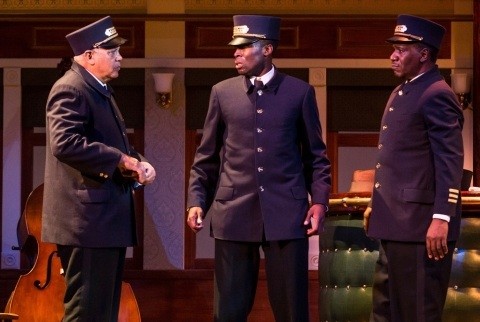

They were dressed to the nines, and no one does male haute couture quite like the African-American male, hoodies and prison grunge excepted. They are all elegance in their uniforms. Costume Designer Birgit Rattenburg Wise has them spiffed up perfectly. They are formal in startling contrast to Sister Juba, who has peacock feathers and poppies jumping out of her hair, and dresses ranging from ecstatic electric red to a green fringed shawl that looks just like an old fashioned lampshade.

The sets are spot on, and make frequent Amtrak riders yearn for the good old days. We admire the plush armchairs, a green leather bar, and wooden doors that open and shut as we move from sleeper to coach to lounge. Riccardo Hernandez is a wizard at creating place and making it suit the action. Projections suggest the speeding train.

In Act II, the future comes perilously close as the youngest Sykes, played masterfully by Tosin Morohunfola, moves closer to the compelling hobo Lutie (Claire Kander). She may be a pied piper on the harmonica but she is also white and that does not go down well. The wonderful background set design suggests Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

Cleavant Derricks is forceful as the middle generation Sylvester, trying to make himself good enough and strong enough for Sister Juba, who he once loved as 'Gertie.' But Gertie is no more, and the brilliant playwright Cheryl L. West resists any temptation for a happy twosome ending.

The thankless roles of a white conductor who is drowning in whiskey and fumbles at women, and the eldest Sykes, Monroe, who is his aide and abettor until the revelation, are created with a subtle delicacy by Frances Guinan and Larry Marshall. Sadly but perhaps not surprisingly, these characters' true colors burst through during an attempted rape. Variety in many roles is only one of the many gifts from director Chuck Smith.

The black essayist Albert Murray died this year at the age of 97. Murray captured the spirit of the Blues on paper. He recognized the Blues as homegrown black music that acknowledges the "essentially tenuous nature of all human existence ... through the full, sharp and inescapable awareness of them."

A band traveling in the lounge represents individual musicians as Murray’s bluesmen, epic heroes who, in his tragicomic lyricism, confront the difficulties of life through the creation of a resilient art. "We invented the blues; Europeans invented psychoanalysis. You invent what you need," Murray said.

In Pullman Porter Blues by Cheryl L. West, the Goodman Theatre elevates our understanding of life. And like all Goodman productions, it provocatively entertains.