The Wasteland Resonates in a Timeline Production

Chicago Gets Another Hit in Susan Felder's Play

By: Susan Hall - Oct 30, 2012

The Wasteland

By Susan Felder

Directed by William Brown

Steve Haggard (Riley), Nate Burger (Joe)

Kevin Depinet (Scenic Designer), Rachel Anne Healy (Costume Designer), Jesse Klug (Lighting Designer), Andrew Hansen (Sound Designer).

Timeline Theatre

Chicago, Illinois

Through December 30, 2012

Photos courtesy of Timeline

While The Wasteland is set in a single underground cell in Vietnam while Americans fight there, both the set and dialogue echo into to a post-apocalyptic world, a dystopian one. Prisoners Riley and Joe may be the last two people on earth, and so they are forced to get along with each other. Two people on The Road, like Cormac McCarthy’s picture. Or a new dystopian universe with little food, little water and no human contact.

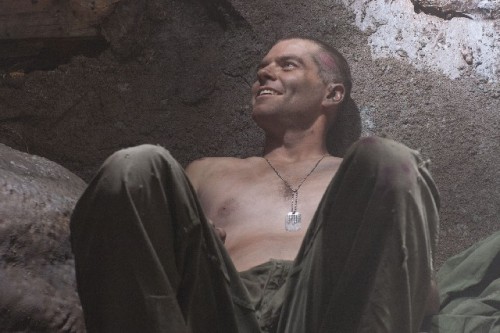

The playwright Susan Felder and the director William Brown succeed in suggesting a broad message without in any way burdening the specificity of the performance. Riley created with variety and presence by Steve Haggard, is on stage, in his cell. Joe is always offstage, but made eminently present in the voice of Nate Burger. The one criticism constantly made in post-play discussions is that we don’t get to meet Joe. That we yearn for him is a testament to Nate Burger’s moving voice over.

The set is more like a tree trunk, a huge one, which is open to us on one side. The sloping earthen floor is broken up by rock. We never know who is bringing food and water. But not eating and drinking is the least of the characters worries. They need contact with each other. What keeps them from going crazy is the sense that there is another concerned if invisible human on the other side of the wall.

As the show proceeds, we learn that Riley had a partner who hung himself after his capture. Riley too is tempted, but talked away from that choice by the redneck who dreams of lovemaking with his girfriend. And loudly practices its reality in his cell. Joe also teases Riley about his gay choice, but stops when he realizes how much that hurts.

The language is spicey and compelling. We are drawn in by dialogue, wondering from time to time about the prospects for survivial or rescue. The world may have gone dim, but the light from the ground grid that forms the roof of the tree trunk prison cell never fails. The play actually begins in blindness and slowly the humanity in two men is pricked and revealed. The two men live a bleak existence, but even in their desparation they choose life, as directed by Brown.

Two unlikely prisoners bond because they have no choice. Listening to Alice Rivlin, Clinton’s budget director, and Pete Domenici, longtime Republican Senator from New Mexico you get some sense of how important it is for people to bond, even if they differ radically in their views and opinions.

The language of the play, often graphic and harsh, does not interrupt the reaching out. If our problems are to be solved, we have to reach across the aisle, or through a prison wall, to keep hope alive and to start down a road which is richer and more productive than Cormac McCarthy’s.

The cell transforms from prison to refuge during the course of the play. Suicide is no longer an option. How to signal their location? Is there anyone out there? Where are their captors and can they be co-opted? All these questions arise only when there is hope. Each man inspires hope in the other, as different as they are. Both men increasaingly push themselves to help the other and in the process help themselves.

Riley sings the country songs he at first dismisses, but then realizes his fellow prisoner Joe needs to hear to go on. Two of the last good guys on earth are trying to survive. We may not be able to protect each other from the evils of the world, but we can provide hope and trudge forward so the human race survives.

Timeline often mounts provocative 'messages', but they never preach. Instead they give great theater writers and actors who deliver important ideas couched in entertaining theater. They do it again with Susan Felder's play.