The Budapest Festival Orchestra at Carnegie Hall

Andras Schiff Delivers a Schubert Piano Concerto

By: Susan Hall - Oct 31, 2011

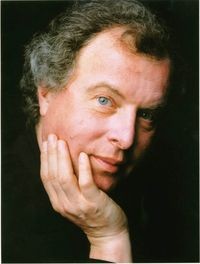

Ivan Fischer, Music Director and Conductor

Andras Schiff, Piano

Budapest Festival Orchestra

Carnegie Hall

October 29, 2011

Bartok, Hungarian Peasant Songs

Bartok, Piano Concerto No. 2

Schubert, Symphony No, 9, "Great"

At a performance of the Budapest Festival Orchestra at Carnegie Hall on October 29, quite by surprise, some critical questions raised by symphony orchestras across the U.S. were answered. The questions involve how to excite audiences and revive enthusiasm.

Maestro Ivan Fischer picked up his baton, and with the woodwinds and the brass sitting in the oval closest to him and the strings behind, commenced a brilliant performance of the unfamiliar Bartok Hungarian Peasant Songs. The music immediately registered on your ears, your heart and your eyes. What is the configuration of instrumentalists on stage? I always crane my neck to look for the clarinetist or bassoonist, and here they are, right in front of me. The first circle in front of the conductor is made up of woodwinds and brass and not the customary strings.

The woodwinds color the tunes as the strings literally dance behind them, standing to spin their bows and create bold beats. You could feel the audience straining to stay in their seats. They wanted to charge into the aisle and dance with the musicians.

These folk tunes are "the electric heartbeat" of Bartok's songs. It is not hard to imagine how much Bartok cared about these rhythms, chants and harmonies as he had trudged around the countryside to find them, lugging the mammoth tape recorders of his day.

The performance techniques of European instrumentalists are much more physical than ours. The forward and backward motion of a clarinetist, for instance, seems to enhance the sound emerging from his instrument. This is true of every performer on stage, including the conductor, who is also a pianist, violinist, cellist and composer.

Of course, not every hall can have the sound quality of Carnegie, but under the Nagawe firm and particularly Yasuhisa Toyota, a new concept of surround sound is being implemented in halls like Disney, the Fisher at Bard, and the newly opened Helzberg Hall in Kansas City. Sound issues in halls not as lucky as Carnegie can now be solved.

In Carnegie, under Fischer, you can hear the direction line of the music and dynamics, but also the texture. Music does not feel like it is moving in a glacial floe of notes, but is rather thick with color and harmony. Fischer does many performances for young people, who respond to his music-making with delight although they may not at first know why.

Bartok's second Piano Concerto was composed at about the same time as the Hungarian Peasant Songs, and also picks up these wonderful tunes, but expresses them in a more sophisticated style. Fischer was joined by his fellow Hungarian, the great pianist Andras Schiff.

Schiff is anchored in Bach, who he plays every day. In his formal approach to Bartok, whose foundation is also in Bach, Schiff brings forward fugal lines and inherent harmonies, which are riveting in his hands. The sheer beauty of the Schiff tone is made even more clear by Carnegie's acoustics. Bartok, a consummate concert pianist himself, intended the piano to be an instrument among instruments, and Schiff honored this instead of pushing a virtuoso display over the orchestra.

As his first encore, Schiff performed a charming Brahms' Hungarian Dance. He followed with Schubert's Hungarian Melody, a tamed down Magyar dance with stress on the offbeats. This foreshadowed the Schubert Symphony that followed.

Starting with a romantic horn solo, the "Great" Symphony, so called because it is long, the allegro grew into a towering structure. The many tunes and harmonies which are proposed are integrated. Mahler's appropriation of the technique makes this Schubert easier to accept today than it was in its own time.

A spicy march follows, performed first by a striking oboe with other instruments joining in. This gives way to a lyrical expanse which Fischer perfectly captured. The Scherzo is short but rich. The final movement is a portrait of high spirits in which all the melodies and rhythmic figures we've heard are summed up.

Robert Schumann, wearing his critic's cap, wrote: "The brilliance and novelty of the instrumentation, the breadth and expanse of the form, the striking changes of mood, the whole new world into which we are transported...there remains a lovely aftertaste, like that which we experience at the conclusion of a play about fairies or magic."

Listening to the Budapest Festival Orchestra at Carnegie, you sense that for color, shading, meaning and detail, they have no equal. No 21st century audience can resist the sound and the furious, glorious music.