Steven Osborne Performs Vingt Regards

A Messiaen Marathon at White Light

By: Susan Hall - Nov 01, 2017

Vingts Regards sur L'Enfant-Jesus

By Olivier Messiaen

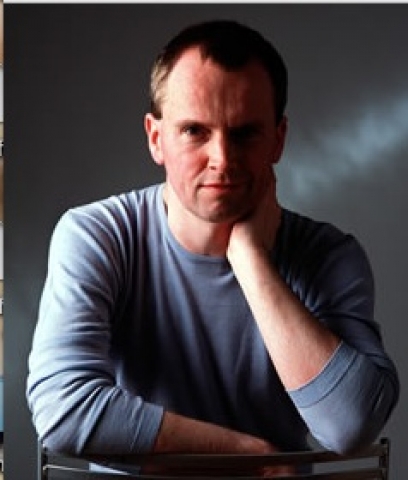

Steven Osborne, pianist

White Light Festival

Lincoln Center

New York, New York

October 31, 2017

This year Lincoln Center's White Light Festival is centered around the idea of faith, which is described as doubt, not certainty. Certainly in Olivier Messiaen's work, total acceptance and emersion in faith is central to the composer's being and his music. Yet expressed in his music, his belief seems as ambiguous as it is deep.

Messiaen had been a prisoner of war when he returned to the German-occupied Paris in 1941. Deprivations did not sour him.“Let us hasten by our prayers the coming of the liberator,” he wrote.

He wanted to compose a “language of mystical love, at once varied, powerful, and tender, sometimes brutal, in multicolored arrangements.” Vingt Regards may have eased his troubles in occupied Paris. The spirituality of these songs is designed to lift us from a troubled world.

The Stanley Kaplan Penthouse at Lincoln Center is a special space. When it is darkened, lights twinkle in the windows and reflections go out into the night. Here Steven Osborne, a consummate pianist, performed Messiaen's iconic Vingts Regards sur l'enfant.

It is unusual for Vingt Regards to be played straight through. Pianist Osborne noted that he had just seen the new Blade Runner film which clocked in at 2 hours 45 minutes. Vingts Regards is 35 minutes shorter and, in any case, Osborne did not want to disturb its arc with an intermission.

Listening to echoes of the East and jazzy rhythms, you sense that Messiaen was open to any interpretation which helped him embrace his God. As he shares Messiaen's central being through the keyboard, Osborne invites us to take the journey through contemplation.

Forewarned, we settle in and turn our ears to the evocative music. Some of these contemplations offer a very quiet hovering over the keyboard, where notes seem barely played, almost spectral. Often great beauty emerges from the upper reaches of the piano. Each ‘regard’ is titled. Contemplating by the Father and then the Son on the Son were particularly delicate suggestions of sound.

In four of the contemplations we are taken into highly dramatic rips across the keyboard. Magisterial octaves are reminiscent of one of Messiaen’s favorite composers, Claude Debussy. The spirit of Debussy informs both the Spirit of Joy and the Noel. Cathedrale Engloutie is suggested in stentorian octaves marching along, sending out overtones which hang in the room. Debussy can also be heard in sweet and quiet Claire de Lune moments of levitation. Notes dangle in the air, a filigree of sound.

The pianist looks at times as though he were playing the organ, which Messiaen did throughout his life. The bass might have been played on foot pedals as the keyboard proceeded above them.

Osborne captures rhythms that the composer augments and diminishes, sometimes inexactly. Close listening is rewarded by these odd and jolting musical ideas. Rhythms are in time, back in time, and with time abolished. Prime numbers of notes get a middle value. Wonderful rhythmic canons appear in Contemplation of the Angels.

Two rhythmic canons are often combined. Osborne remarkably brings them out to us. The pianist finds beauty in the atmosphere of several tonalities. Often the impression is unsettling.

The various modes Messiaen deploys are also disquieting. One mode has two half steps, then a minor third, and then a half. We heard it in Son on the Son and also Silence. Yet when modes are connected, the last note of one is the first note of the next, smoothing transitions.

Doubling rhythmic values and cutting them in half also adds to an unnerving feeling. It is odd to feel at once the reverence and at the same time to be rattled by strange and affecting sounds.

Stalactite figures appear in Contemplation of Time and contrasting lights glitter when the shepherds and wise men arrive. Overlaps, plainchants, all sorts of wizardry combine to uplift in the facile hands of Osborne. One could almost see the eggheads of Giorgio de Chirico who inspired Time.

Colors are also pictured in notes. The snow white synthesis of all pigments suggests purity and virginity in “Through him everything was made."

These moments only begin to describe the richness of the music and the performance.

It might have been helpful to have projected titles, because the composer clearly wrote title ideas as a jumping board for each song. I wanted to lie down on a mat and look up through the ceiling, completely relaxing into the floor to focus as the music unfolded. Even seated, which we do after all for Blade Runner, Messiaen's message, urgent and yet peaceful, emerges from Osborne's magical hands. Messiaen delivers the theme of this year’s White Light Festival. We swirled in mystery, yearning and the power of faith.