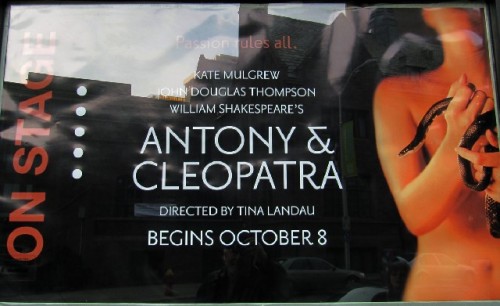

Antony and Cleopatra at Hartford Stage

Kate Mulgrew and John Douglas Thompson

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 02, 2010

Antony and Cleopatra

By William Shakespeare

Directed by Tina Landau

Scenic Design, Blythe R. D. Quinlan; Costume Design, Anita Yavich; Lighting Design, Scott Zielinski; Original Music and Sound, Linday Jones; Fight Director, Rick Sordelt, Wig Design, Tom Watson; Casting, Tesley & Company; Stage Manager, Barbara Reo. Cast: Kate Mulgrew (Clepoatra), John Douglas Thompson (Marc Antony), Keith Randolph Smith (Enobarbus), Scott Parkinson (Octavius Caesar), Christoher McHale (Lepidus), Alex Cendese (Pompey), Sean Allan Krill (Agrippa), Kendra Underwood (Octavia).

Hartford Stage Company

October 7 to November 7, 2010

In 2002 Kate Mulgrew premiered the one woman show Tea at Five at Hartford Stage. The play focused on Katherine Hepburn was a great success with eleven productions in other cities. In popular culture she is a cult figure for her long tenure as Captain Kathryn Janeway on the TV series Star Trek: Voyager.

Through November 7, she has returned to Hartford Stage in an elaborate, ambitious and galvanic production of the infrequently staged tragic romance Antony and Cleopatra. For women it is the role in Shakespeare’s canon on a par with Othello, Macbeth, Hamlet, Richard III, and Lear.

While Romeo and Juliet is more accessible and commonly produced the role of the historical Cleopatra VII represents one of the most powerful and tragic women of history. She seduced, manipulated, had children by, and matched wits with, no less than Julius Caesar, and then his greatest general, Marc Antony. Along the way she survived by battling with, and then ordering the murder of, her brothers, husbands and co rulers first, Ptolemy XIII, and then, Ptolemy XIV. She briefly co ruled as queen of Egypt with her son, Caesarion, by Julius Caesar.

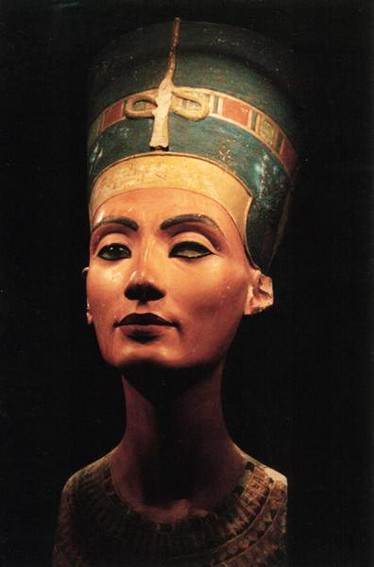

In the Egyptian tradition the royal title was passed to the oldest daughter of the primary queen. The norm was for her husband, often her brother, to rule as Pharaoh. There were other rare examples of Egyptian queens as sole rulers, the most famous of which was, Hatshepsut (1508–1458 BC), during Dynasty XVIII. Scholars believe that Nefertiti (1370-1330 B.C.) may have briefly been sole ruler in the time between the murder of her husband, Ankhenaten, and the brief reign of his son by a minor queen, Tutankhamun. Nefertiti bore three daughters and produced no male heir.

The historical Cleopatra endures as one of the greatest and most fascinating women of history. It is what inspired Shakespeare to write a play based on his reading of Plutarch (46-120 A.D.). The burden of the play is that he tried, perhaps too hard, to be faithful to the complex history of the fracture and civil war that followed the assassination of Caesar in the Senate on March 15, 44 B.C.

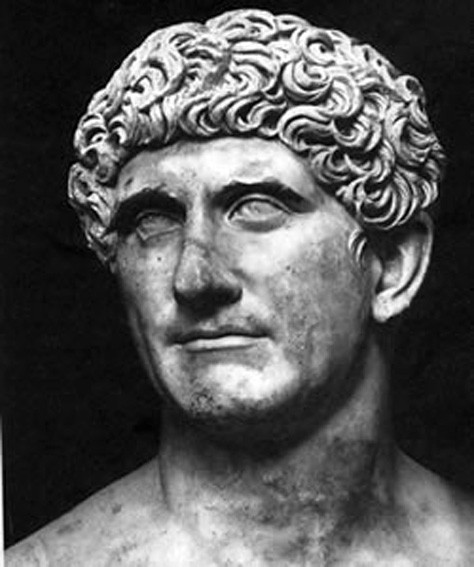

Shakespeare wrote Julius Caesar, in 1599, and Antony and Cleopatra between 1606 and 1608. There is more focus and dramatic power in the earlier play. By comparison, the story arc is relatively simple to follow. Marc Antony emerges as one of the greatest and most noble characters of that epic. His funeral oration “Friends, Romans, Countrymen” is memorable and compelling. It is surely the greatest single moment in the play. In his fourth film, in 1953, Marlon Brando portrayed Marc Antony in a Hollywood production of Julius Caesar.

It is, however, a very different Antony whom we encounter during the opening scene of Antony and Cleopatra. In this Hartford Production we encounter him, as played by one of our finest classical actors, John Douglas Thompson, literally, rolling about on the palace floor. Like Alexander the Great before him, the austere and disciplined general and conqueror has gone native in debauched excess. Having conquered the world, Alexander was consumed by it. Like Jesus, Alexander was dead at 33.

Alexander of Macedon had a unique approach which was admired by Machiavelli in The Prince. When he defeated his greatest enemy, Darius, he married his daughter Roxanne. He ordered his generals to marry princesses. Then the Greek soldiers took Persian wives. In so doing Persia was not just conquered by the Greeks; it became assimilated and Hellenized.

When Alexander died, in 323 B.C., the empire was divided among three of his generals. Ptolemy (367-283 B.C.) founded the Ptolemaic or Hellenistic dynasty which ended with the death of Cleopatra in 30 B.C. Egypt became a Roman province thus concluding 3,000 years and 30 dynasties of Pharonic rule.

During the 250 years of the Ptolemys the rulers of Egypt were essentially Greek. Its capital was Alexandria which flourished as a hybrid of Egyptian and Greek, art, culture, history and religion. One of its greatest accomplishments was the Library of Alexandria which perished because of the Battle of Actium. The burning ships of the fleet of the defeated Antony and Cleopatra set fire to the city.

Hartford Stage has mounted a large, energetic and robust production. Between the debauched scenes of revelry, feasting, music, and dance, or the battle scenes, there is a lot of action and related movement. The actors, through some 43 scenes, divided between Egypt and Rome, are in perpetual movement. They charge up and down the aisles, come and go through stairs leading to the stage floor, or scramble over scaffolding to another level. The audience looks down on the bare floor through which is a bisecting band of blue. During the beginning of the second act plexiglass sections are removed to reveal a trough of water. This is a signifier for the Nile which is emblematic of Egypt.

The scenic design of Blythe R. D. Quinlan, and the exotic blend of Egyptian and Roman costumes by Anita Yavich, combine to give the production much of its visual panache. The heat of Egypt provides a feast of flesh with bare chested men and scantily attired women including Mulgrew. The wonderfully diverse and exotic music of Linday Jones often evoked the score of the magnificent HBO series Rome. The lighting of Scott Zielinski, however, was often so bright and harsh that the theatre seemed more like a tanning booth.

In the program we counted some 32 actors. Many of them, including Thompson, are African American or Hispanic. It is an interesting reflection on the period of history which is depicted. By granting Roman citizenship to conquered nations, as had Alexander and the Greeks before them, they eliminated borders and boundaries. One was free to travel and trade from one end of the Empire to the other. Roman government and law was applied equally to all of its citizens. The era of Pax Romana provided unprecedented and sustained stability to a vast Empire.

The expectation of Roman citizenship was an acceptance of the Roman gods, law, and language. Only the Jews refused to accept these terms leading to the destruction of Jerusalem under Titus in 70 A.D. and its consequent Diaspora.

The Partician, or ruling class, of Octavian/ Augustus and Marc Antony, scorned intermarriage and assimilation. They took great pride in descent from the founders of Rome. Only through exceptional circumstances of wealth, and military success, were Plebians able to rise in social status and political power. There were three classes of Romans: Patricians, Plebians and Slaves. Those who were beyond the vast boundaries of the Empire were Barbarians.

The associations of first Caesar, and then Marc Antony, with the Egyptian/ Greek queen Cleopatra evoked resentment by Rome’s Patricians. In 46 B.C. Cleopatra and her son Caesarion moved to Rome. Caesar dedicated a gold statue of Isis to a temple in her name. Tongues wagged as everyone knew of the affair. Caesar’s daughter Julia (wife of Pompey) died in childbirth leaving the bastard Caesarion as his only child. But when Caesar’s will was read Octavian, his nephew, was named as heir to the Empire. Cleopatra returned to Egypt and, during the civil war that followed, allied with Octavian and Antony, in their conflict with Brutus and Cassius. Both sides conspired for her wealth, troops and grain. Cleopatra had assets to deal in the power struggles.

Of course, this gets far too complicated. If it is difficult to keep focused in a review imagine the challenge of trying to follow the drama on stage. Even with a reduction of a third of the original text the Hartford production runs for two hours and forty five minutes with a single intermission. There are so many sub plots and diversions that we found our attention racing up and down the aisles like the peripatetic actors. There is much about the play that becomes a blur.

Part of that is unfamiliarity with a work that is rarely produced. There are none of the great, familiar soliloquies. We lack those signifying moments when we come to attention. They may be there but we have to find them on our own. There is, for example, a great scene when Cleopatra, through a messenger, learns that Antony has married Octavia, the sister of Octavian. There are wonderful lines as Mulgrew probed for information. She demanded of the messenger an accurate description of her rival.

In the play we catch but a gratuitous glimpse of Octavia (Kendra Underwood). The marriage produced two daughters while here she is presented as little more than an expedient dalliance.

We are moved by Antony’s respectful, but apathetic, response to the death of his wife Flavia. It was his third marriage to a woman he didn’t love. As a widower it allowed him to strengthen an alliance with Octavian through Octavia.

Since Antony married several times for social position and power we are unclear about his attraction to Cleopatra. Does he desire her as a woman and love interest or for the vast wealth and power at her command?

It is only during the second act, when Cleopatra has seemingly betrayed him and sent the false message of her death, that we come to feel the depth of Antony’s love. It is a great scene of deception and despair. He orders a servant to kill him. He anticipates the thrust of the sword. Only to discover that the faithful soldier has taken his own life. It leaves Antony no choice but to fall on his own sword. While dying he learns that Cleopatra lives. There is an awkward scene in which they are reunited.

The scene in which Cleopatra takes her life Mulgrew played with passion. Augustus had planned to drag her in disgrace through the streets of Rome. With a snake she cheats him of that humiliation. Although Augustus ordered the murder of Caesarion he spared the other children of Antony (daughters by Octavia) as well as his twins by Cleopatra.

This production has compelling moments. It is readily evident why Mulgrew aspired to this great role. Rightly it is a jewel in the crown of a great career. She is matched by a superb Antony in Thompson. Indeed, they make sweet music. But fully appreciating the magnitude of their theatrical accomplishment entails enduring a complex and often obdurate plot.

This play wants to be a love story but in remaining faithful to political intrigue, raw ambition, and struggle for power it is daunting to remain focused on the protagonists. The director, Tina Landau, and a superb cast, deserve enormous credit for taking on such a daunting challenge. It is hard to imagine a better production. If it doesn’t all work then blame it on the Bard.

Why then is Antony and Cleopatra aspired to by the great women of each generation. Consider that she has been portrayed by Mulgrew at 55, Venessa Redgrave, at 60, Tina Packer at 67, and currently, Kim Cattrell at 54 (In London). We are asked to set aside preconceptions of the historic figure. Cleopatra was just 21 when, in 48 B.C., she had an affair with Caesar who was 52. She died at 39 while Antony may have then been between 53 and 56.

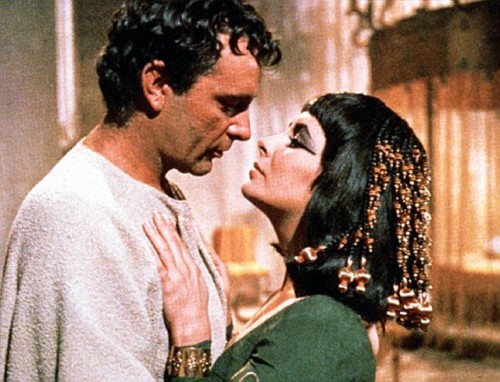

In the 1963 film Cleopatra, one of the most expensive all time flops, Elizabeth Taylor was 31 and the then relatively unknown Welsh actor, Richard Burton, was 38. In one of the great love stories of our time Taylor abandoned her husband, singer Eddie Fisher, and Burton divorced his wife Sybil. Burton and Taylor would later divorce then remarry and divorce again. The classic Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf is an artifact of their destructive relationship.

When we evoke Cleopatra surely the 31 year old Taylor looks the part. The film, of course, was just awful. It seems the real Antony and Cleopatra took place off camera. But, for me, the image of Cleopatra is conveyed by the Amarna style naturalism of the magnificent bust of Nefertiti. It is simply the greatest of all Ancient Egyptian masterpieces. It is so much more beautiful and compelling than the numismatic evidence of the historical Cleopatra depicted in profile. There are some surviving sculptures but they only hint at her actual features.

While one of the legendary beauties of ancient history was she, as Plutarch implies, more clever and witty than pretty. Does it make more real her concerns about the beauty of Octavia? Just how did Shakespeare see her? And of, course, how do great actresses present her?

This is the focus of Tina Packer’s Women of Will. She has created a collage of all of his roles for women with connecting commentary. Packer’s thesis is that, with time, he evolved in his understanding of women. Coming near the end of the canon Cleopatra may be a culmination of that process. And, as such, among the greatest of his roles for women.

From that perspective it is understandable that it takes maturity and life experience for a great artist to portray the Egyptian queen. One might argue that Antony, a man of action corrupted and weakened by time, and the pursuit of pleasure, is no less challenging for an actor. They are great roles but we have to slog through too much underbrush to get to them.

There are back story diversions like the Triumvirate with Lepidus and war with Pompey. Just what do we make of the frat boy antics on Pompey’s vessel? While amusing it is just a distraction. Octavian/ August was played with chilling cruelty and ruthlessness by Scott Parkinson. His subplot runs parallel to Antony and Cleopatra and at times overwhelms the drama. Another role and performance that provides great balance and depth to this production is the wonderful Keith Randolph Smith as Antony's second in command Enobarus. Smith poignantly conveys despair at having betrayed Antony.

Ultimately, Antony and Cleopatra, were pawns as Octavian cut his way through a field of opponents. He consolidated the fragments of a shattered empire and founded the brutal Julian/ Claudian dynasty of the Twelve Caesars.

Hail Caesar.