Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. Publishes a Critical Study of American Art

Rethinking American Art: Collectors, Critics, and the Changing Canon

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 02, 2025

Rethinking American Art: Collectors, Critics, and the Changing Canon

By Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr.

Published by Godine/ Boston, 2025

422 Pages, illustrated with bibliography and index

ISBN 978-1-56792-834-1

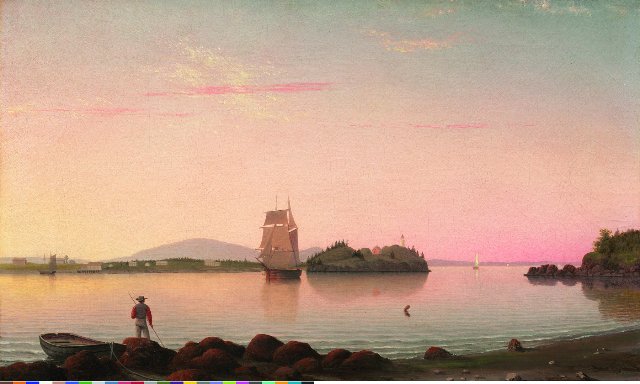

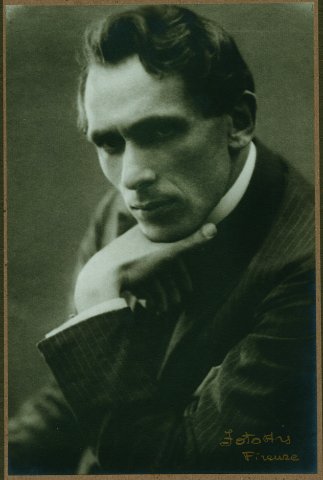

Now retired, Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. (born August 11, 1938) a specialist on the work of luminist, Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), was a leading curator and scholar of American art.

From 1977 to 1999, Stebbins was the John Moors Cabot Curator of American Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. During his tenure, he organized nineteen exhibitions on subjects ranging from 18th century artist John Singleton Copley to The Lane Collection of modern art. As curator, he guided the museum's acquisition of over four hundred paintings, from 17th century limners to Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol. From 1968 to 1977, he was Curator of American Paintings at Yale University, as well as an associate professor of art history for the university. At Yale, he built the collection of 19th century American landscape and still lifes; his major purchase was Frederic Edwin Church’s Mt. Ktaadn (1853). After the MFA he became founding curator of American Art for the Harvard Art Museums.

More than a memoir of a distinguished career he has written an intensive critical study of the entire field of American art. On many levels it reboots our thinking. It’s an absorbing study for anyone with interest in art but should be intensely read and taken to heart by collectors, curators and scholars.

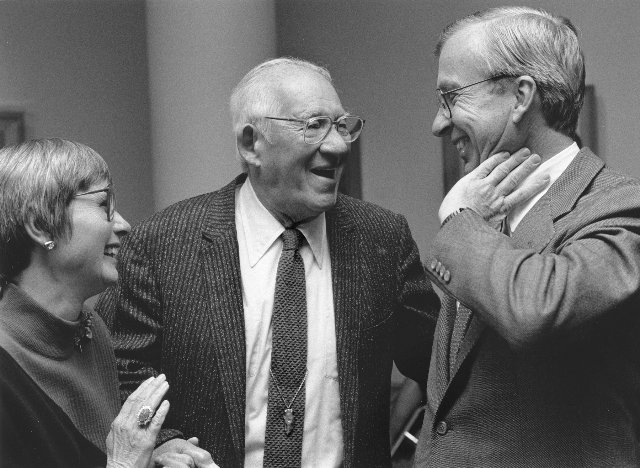

Writing in an anecdotal manner it felt like a conversation with Stebbins much like the many we have enjoyed, since the late 1970s. He was a curator at the MFA while I was a critic covering his exhibitions.

The main point of his book is the exposition of how taste and the canon shift with generations. This is particularly relevant to collectors who approach the art market as a resource for investment and speculation. Until recently the great museum and private collections were assembled by collectors and curators who Stebbins identifies as possessing a “good eye.” By getting in on the ground floor they were able to acquire works for modest prices that later soared in value.

Collectors like Maxim Karolik (1893-1963) and William H. Lane (1914-1995) never paid more that $5,000 for works now regarded as priceless. The 6,000 photographs that he and his wife Saundra acquired at the time sold in the hundreds not thousands of dollars. At the other end of the spectrum are today’s mega collectors like Alice Walton and Eli Broad who pay top prices in an inflated market for the best works.

The early chapters of the book made me feel like being back in graduate school. Years ago I read the three volumes, encyclopedic “History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States” (1834) by William Dunlap. In 1867 Henry T. Tuckerman wrote about a dozen or so artists in “The Book of Artists.” They established the founding canon of American art. Dunlap most admired Benjamin West with whom he studied in London. Another favorite was Washington Allston. The Museum of Fine Art’s first acquisition was Allston’s “Elijah in the Wilderness” a gift from the Boston Athenaeum.

Stebbins describes his role in securing co-ownership of the Athenaeum’s George and Martha Washington portraits when that institution decided to sell the pair. They now cycle between the MFA and the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

As each generation publishes its histories Stebbins keeps track of who and what is in or out. The first part of the book is organized as Critics and Canons. The chapters cover canons, museums, critics, writers, the discovery of American art, exhibitions and publications. There is much detail to absorb before the pace of the book accelerates.

The second phase of the book, often a page turner, discusses the major collectors who are often as fascinating and eccentric as the works they pursue. The first such chapter is “The Wounded Collector Grenville Winthrop.” The descendant of the first governor of Massachusetts he was reclusive but curmudgeonly. He set a fine table for those who visited his Lenox estate. He was a neighbor but not friendly to Edith Wharton.

We learn about the feuding Clark Brothers, Stephen and Sterling. The former dispersed great works to the Met while the latter created one of America’s finest and best endowed small regional museums in Williamstown.

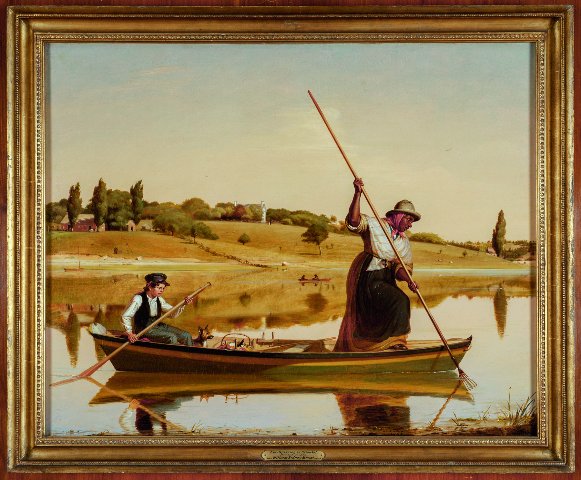

Maxim Karolik was a Russian born Jewish opera singer. He married a much older heiress Martha Codman. Together they gave a great collection of American furniture to the MFA. At fifty he started a collection of American landscape and genre paintings as well as outsider or folk art. While instrumental in making the MFA one of the top three museums for American art he was snubbed by Boston society and the museum’s trustees. He and his wife resided in a Newport mansion where he remained after her death.

Stebbins is emphatic about the anti Semitism that Karolik experienced but has largely evaded that in discussion of the Boston Expressionists. Other than works in the Lane collection by Karl Zerbe and Hyman Bloom he did not pursue further acquisitions. He had no interest in Jack Levine who has largely been ignored as a significant Boston artist. There was to be a Levine show at the Boston University Art Gallery but Pat Hills described how the project tanked under the curator who followed her.

There are many pratfalls in the story of contemporary art in Boston. Stebbins is frank in telling some of them at the expense of the MFA’s founding curator of contemporary art, Kenworth Moffett. Told by MFA director, Jan Fontein, to visit the collector William H. Lane, he reported back that there was nothing of interest.

In a spellbinding chapter that changed when Stebbins pursued Lane. Eventually 100 key works came to the museum followed by 6,000 photographs. That vaulted the MFA up the depth chart of American art collections.

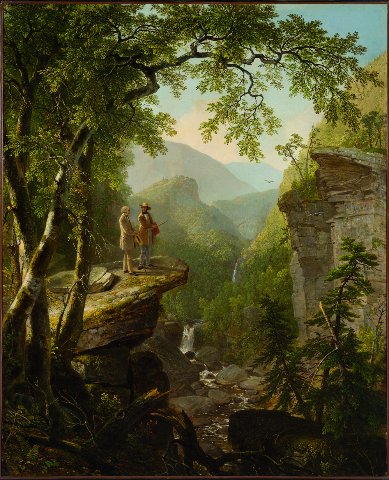

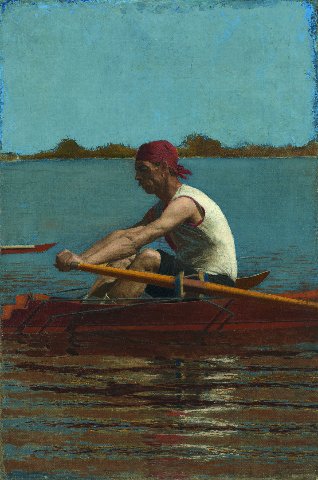

When Walmart heir, Alice Walton, opened Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, she was widely regarded as a pariah by the art world. With deep pockets and voracious zeal she pursued masterpieces. “Kindred Spirits” by Asher B. Durand had long hung in the New York Public Library until she purchased it. She pursued the seminal “The Clinic of Dr. Gross,” 1875, by Thomas Eakins. It was owned by Jefferson Medical School where he taught. Some $68 million was raised to keep the painting in Philadelphia where it is jointly owned by The Philadelphia Museum of Art and Pennsylvania Academy.

With skepticism we visited the museum after it opened in 2011. Set in the woods the entrance entails a descent to the pavilions hovering over water designed by Moshe Safdie. There was a thrill of recognition of masterpieces like Richard Caton Wooodville’s genre painting “War News From Mexico” which was originally owned by the National Academy of Design in New York.

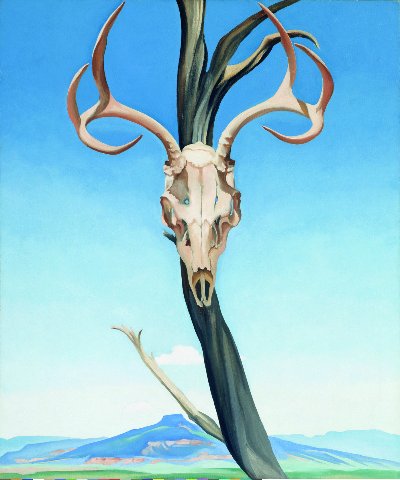

In 1949 Georgia O’Keeffe gave a portion of the Steiglitz estate to historically black Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The important collection of early modernism remains intact and is co-owned by Fisk and Crystal Bridges. It was in Bentonville during our visit and rotates back to Fisk. There Walton has paid to upgrade its museum and provide for conservation.

Stebbins has kind words, rightly so, for Walton, her eye, and philanthropy. Through a bussing program the museum has become a formidable educational resource for the region. During their visit students are also provided with a meal. The museum has expanded its programming to contemporary art.

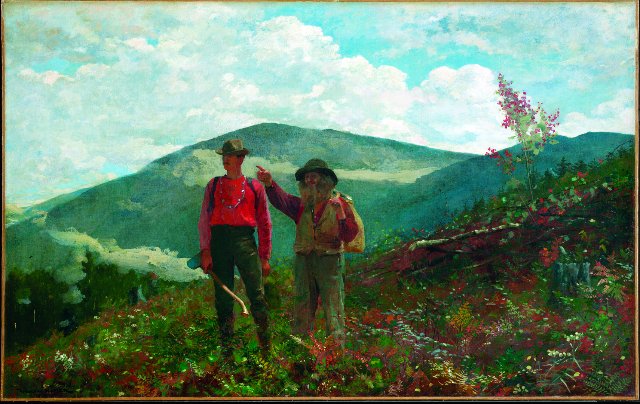

For Colonial portraits and works by John Singleton Copley Boston dominates as does Philadelphia for Thomas Eakins. Several museums, including Clark Art Institute, the MFA, Met and National Gallery share depth in Winslow Homer. For the genre artist George Caleb Bingham visit St Louis.

The discussion of how artists slip in and out of favor is intriguing. An artist who has run the gamut of appreciation is John Singer Sargent. His mural projects have been deemed turgid and enervating. The society portraits are a misfit in current social-economic evaluations. The watercolors and views of Venice, however, have proved to be enduring.

Building on strength Stebbins bought Sargent as well a once fashionable Boston impressionists Edmund C. Tarbell and Frank Weston Benson. Given the glaring areas of non representation, Jewish, African American, contemporary Boston, and women artists, these are resources that might better have been allocated. In the later chapters Stebbins has come around on the topic of diversity. This came as a surprise to me.

We learn that the best scholars, collectors and curators make mistakes. Barbara Novak published American Painting of the Nineteenth Century: Realism, Idealism and the American Experience in 1969. Her second book, Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 1825-1875, was described as "the most important contribution to the understanding of nineteenth-century American art that has been written in our generation" by John I. H. Baur of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Her second book was the text used for courses on 19th century American art. Stebbins notes that she did not include the seminal landscape painter Frederick Edwin Church.

The collector Karolik also muffed on Church. He bought what he thought was a major work that proved to be by a follower. He failed to correct this error. Today the major holding in works by Church are in the Wadsworth Athenaeum.

Lane was friendly with abstract expressionist Franz Kline and bought a group of smaller full color works before the artist famously transitioned to larger black and white paintings. Lane asked if there were other artists he should consider. Kline suggested Jackson Pollock. But when Lane met Pollock in a bar the artist was drunk and nothing came of the interaction. One may imagine the difference for Lane and the MFA had the artist been sober and more cordial.

In 1983 Stebbins curated “A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting, 1760-1910” which was shown at the MFA and then the Louvre. The exhibition did not include work by African Americans or other minorities. There were protestors in front of the museum. They were invited to meet with Stebbins and director Jan Fontein. They made a case for including Henry Ozawa Tanner (1859-1937).

As Stebbins clarified by e mail " On the Tanner controversy: yes, we included a great Tanner in the Paris exhibition, and yes we redid the catalogue to include it. The new catalogue had the Bingham Fur Traders on the cover, And I do reference the issue pretty thoroughly, see p. 94 of my book."

Stebbins has come around on Tanner who he now feels belongs in the canon. Museums have pursued acquisitions.

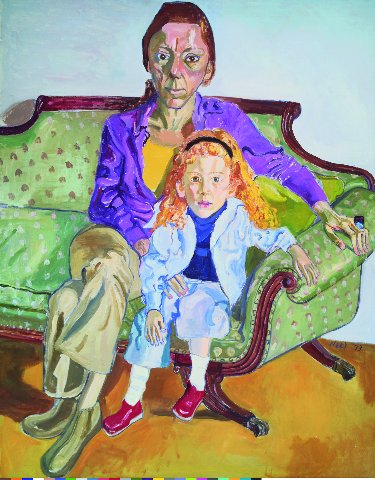

Part three of the book largely addresses his change of heart. Under the heading Today the chapters include “The Recognition of Racism and Misogyny” “Museums Reset” “Native Americans Reconsidered” and “Changing Taste.”

Arguably this is the most original, radical and provocative aspect of the book. It is an attempt to grasp and clarify a complete reversal of the field and everything that informed his curatorial practice.

In this paradigm shift, arguably, there are no masterpieces and the notion of an agreed upon canon is in freefall. Museums have rehung their collections with an emphasis on diversity. We first saw this during a tour of Canadian museums with prominent inclusion of First Nations artists.

This radical transformation occurred when Matthew Teitelbaum was director of the Art Gallery of Ontario. He took that approach of diversity as director of the Museum of Fine Arts from which he has recently retired.

In addition to rehanging museum collections there is a development in wall labeling. Next to Colonial and 19th century portraits, for example, we are informed of sitters who were slave owners. The Trump administration has attacked the Smithsonian Museums for this approach.

Stebbins observes that the Joseph Stella painting “Brooklyn Bridge,” one of his proudest acquisitions, is no longer on view. The taste of a new generation of curators and scholars has been informed by social justice and theory. If works of art tell the story of America museums are invested in conveying a new narrative.

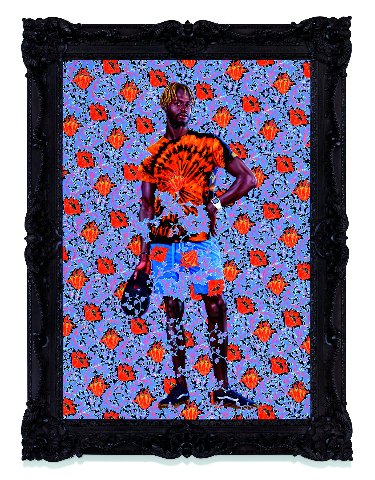

As always these changes are reflected by mega collectors and the volatile art market. Vast fortunes acquired through sports and entertainment has boosted the value of African American artists past and present. Museums are scrambling to acquire the best works.

To a lesser extent this paradigm shift has been reflected by a focus on Native American works. When the new Art of America galleries were first installed by the MFA there was token and least prominent display of this work.

That has changed. Jaune Quick to See Smith, a leader for her generation, lived long enough to see her retrospective installed by the Whitney Museum of American Art. Jeffrey Gibson represented America in the Venice Bienalle. A large installation of his work is currently on view at MASS MoCA.

While the field is different today, as Stebbins states, it will change again.