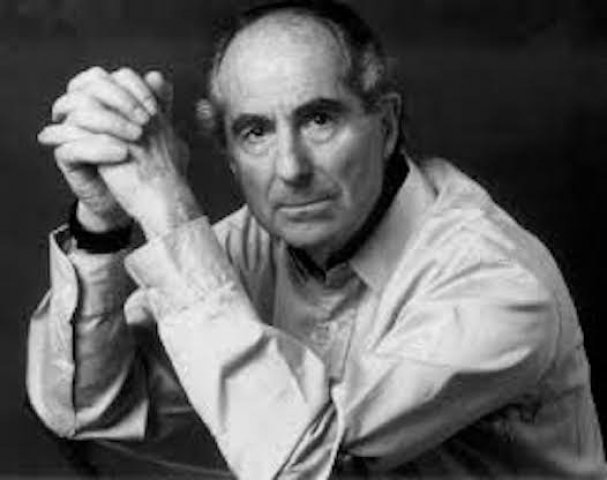

Philip Roth’s Books Return Home

Distinguished Author Gifts Newark Public Library

By: George Abbott White - Nov 03, 2016

It’s not often imagination runs into reality and comes away a winner, or at least even. Philip Roth has made this encounter happen more than once with his celebrated stories and novels over half a century. He offered me the experience three times last Friday evening at the Newark Public Library, the epicenter of his creativity.

Roth recently announced the decision to donate to his old Newark haunt some 3500 volumes of his personal working library, books currently jamming the halls and stuffed into the closets of his Connecticut home. His hometown’s response was grateful and enthusiastic. A new, specially-designed space in the Main Newark Library will “house and showcase” Roth’s often-annotated books. A reception was given for friends and literary notables, and immediately afterwards, hundreds jammed the inaugural “Philip Roth Lecture Series,” given by novelist and essayist Zadie Smith. She was personally chosen by Roth for the honor.

Readers of American literature recognize a number of iconic sites—Thoreau’s Walden Pond or Harte Crane’s Brooklyn Bridge, Fitzgerald’s Plaza Hotel or Hemingway’s Big Two-Hearted [Fox] River. So who will now forget the huge pile in Newark, across from the park where Washington drilled his revolutionary war troops? Built in 1901, Roth in a note which was read remembered the library’s “grand facade” and its “thousands and thousands of books, and its gloriously inviting open stacks,

where you could sit yourself down on the hard floor of a narrow aisle between the walls of shelves and find there, in front of you and behind you, above and below you, not only the book you were looking for but dozens more on the same subject that you had never heard of.

During his first year of college at the tiny and makeshift Newark Rutgers campus, describing a situation familiar to many of his generation, Roth wrote,

the stacks and the reference room and the reading rooms [of the Newark Public Library]…were where I camped out when I wanted a quiet place to be alone to read or to study or to look something up. It was my other Newark home. My first other home.

And, compared to much of pre and post-World War Two Newark, what an amazing other home.

Four stories high, impressive brick and limestone facing, modeled after the Florentine Palazzo Strozzi palace, any visitor—like that now famous “little colored kid,” in Roth’s remarkable first effort, the 1959 novella “Good Bye, Columbus,” had to be impressed. Imagine being granted access and seeing the high ceilings and tall arched windows, rich marble columns, wainscoting and floors, open three stories high atrium, and then, able to enter those (innovative, for then) open stacks. Row upon row, unrestricted access to places where other worlds could be glimpsed at leisure.

Stacks where that “little colored kid” could hide out with the “heart” books, slowly turn the large format, richly-colored portraits of lightly clothed Polynesian women by “Mr Go-again,” and imagine himself, like his yearning twin, the novella’s protagonist Neil Klugman, undisturbed for the time to enjoy and possess—like another yearning youth, Jay Gatsby—those fabulous lands with their uninhibited and welcoming inhabitants.

In from the rains and no sooner swiveling at the atrium’s base, eyes up and down wide open, trying the sweeping marble staircase and quickly agreeing that imagination and reality very nearly coincided, I was tapped on the shoulder in the reception room, Fifties jazz in the background.

Did I know “M.I. Finley?” asked a tall, burly, older gentleman in what looked like a worn, brown leather Eighth Air Force pilot’s jacket. “Sir Moses?” I replied, adding, “Of course, everyone knows he was one of the greatest classical scholars of the 20th Century. A politically-harassed American who took the 5th Amendment in the early Fifties, and luckily landed on his feet at Cambridge University. He wrote a dozen or more books, several path-breaking, not least on the ancient economy.”

I was corrected, or amended. “Moses Isaac Finkelstine,” said my new biographical source with emphasis. “What?” caught off guard. “He taught us at Newark Rutgers, a few blocks away.” Wheels suddenly began to turn, pieces banged into one another. “Tony” smiled, introduced himself as a childhood friend of Roth’s. “We lived near one another, attended Weequahic High School together.”

There was more, including personal details of Professor Finley only someone who knew him at first hand could know, including how he was taken on at Jesus College, and the manner of his death.

Imagination accelerated. In Roth’s story about the Red Scare and a high school teacher in the early Fifties, “You Can’t Tell a Man by the Song He Sings,” two working class Italian pals of a bright Jewish student join forces and successfully stage a “palace revolt” against their “Occupations” teacher who trusts in tests, though themselves avoiding a “record.” Near the story’s end, our Jewish student narrator relates how a “Senate Committee swooped through the state” and discovered (from nearly two decades earlier) the formerly Marxist teacher’s “record.” When he refuses “to answer some of the Committee’s questions,” the teacher is “dismissed.”

Not wanting to connect those dots right away and hearing that Tony had, like Roth, studied philosophy at the University of Chicago, I wondered if Tony ever had a class there with one Manuel Bilsky, the exacting philosophy professor of my best friend and a decorated WW2 soldier who was also reputed to be the animating “figure” behind Roth’s powerfully ironic story “Defender of the Faith.”

Yes, he and Roth had Bilsky, before Bilsky moved to Roosevelt University, ending up at Eastern Michigan near Ypsilanti. Battle-tested and battle-weary, neither orthodox or even overtly religious, Sgt Marx of the story is returned to the U.S. to train draftees and finally forced, by three (Jewish) privates in an escalating series of shifty and slippery ethical encounters, to “defend” their, and his, faith. Deftly turning the tables on the most manipulative of the three, Marx sends him to the Pacific while Marx sends himself—he believes—to a lifetime considering what he has done and why.

No lockstep correlation between tidbits of reality and the texts imagination produced occurred that Friday night. A bad idea anyway. But in future years perhaps some young reader turning the pages of Roth’s copy of Bill Mauldin’s cartoons or Ernie Pyle’s reportage, A Farewell to Arms (which Roth read age 23) or Madame Bovary (which Roth read age 25), may catch a word, hear a phrase, see an image and sense, in that moment, the electric jump from one point to another that became art.

P.S.

Zadie Smith was terrific, she’s on my reading list.