Beckett's The End Staged by Gare St. Lazare Ireland

White Light Festival Presents the Lovetts

By: Susan Hall - Nov 04, 2015

The End

By Samuel Beckett

Gare St. Lazare Ireland

White Light Festival, Lincoln Center

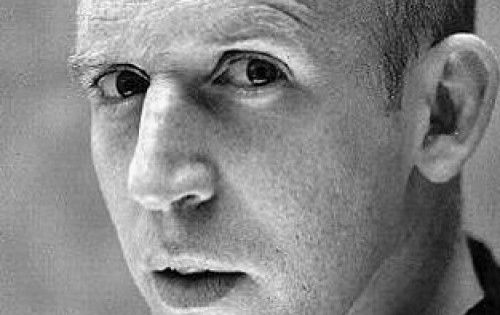

Conor Lovett, Actor; Judy Hegarty Lovett, Director; Mike Gunning, Lighting Designer; Maura O'Keeffe, Associate Producer

New York, New York

November 3, 2015

Gare St. Lazare Ireland and Conor Lovett, actor, directed by Judy Hegarty Lovett make a strong case for Beckett as a dramatist in spite of himself.

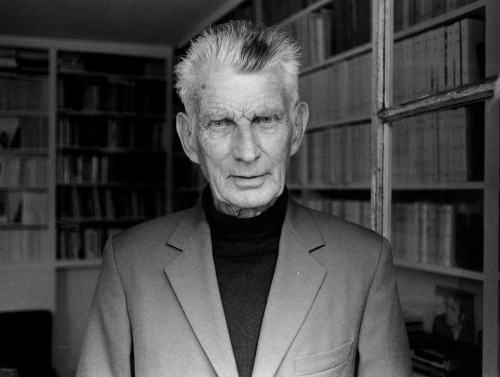

Of course Beckett helps. As he wrote The End, immediately after the end of the Second World War, he has dispensed with language as a way to convey the unknowable-ness and never-ending-ness of life.

Narrating the meanderings of its expelled character, clothed in a dead man’s clothes, reminiscing about the copy of Arnold Geulincx’s “Ethics” (1624) which had been given him by a former tutor, the protagonist finds himself looking for a room.

The creature, at times as much animal as man, is able to rent a single room having his meals delivered, and his chamber-pot emptied, by an anonymous woman. It is a return to a primal scene of mothers but also setting the speaker of the tale in the position of an animal in a zoo. Lovett gives us the tramp as ugly and funny.

Lovett is a monologist, the form Beckett was driven to in fiction: Molloy, Malone Dies, The End, and a decade later on stage as Krapp’s Last Tape. As the semi-feral creature has been ejected from the world, so the past is thrown out, [The world's] "gates have slammed behind me. I have burrowed my way out alone."

How do you create a Beckett protagonist? Conor Lovett has a powerful answer.

Taking The End as a series of incidents, Lovett treats each one differently. Leaving an institution, perhaps an asylum, with a few dollars in his pocket, a tramp finds a basement room. Here Lovett is small, keeping to himself, sharing only because he is speaking, not because he is reaching out, or describing.

Again on the street, the creature, dressed in a dead man’s clothes, he finds another home in a boat which he covers with a board to keep the rats away.

Lovett now physicalizes the creature, crumpled and curled up, giving the sense of his entrapment in the boat, but also of the will to survive displayed in humor. Rats have trouble climbing up the curve of the boat's hull, but even if they did, this creature would continue on, undeterred, scratching his private parts because this is more satisfying than masturbation.

From time to time, the creature’s mouth moves without words, his eyebrows lift, his ear cocks, but there is no sound. Lovett struggles as Beckett did to convey the ineffectiveness of words to reveal a state of menace and adversity. Exiled, expelled and unable even in death to ever come to a rest.

Taking up begging, the creature finds himself an exhibit and victim of a political harangue. Lovett takes on three roles: the beggar, the orator and the crowd.

Lovett turns this into street theatre which crescendos as the orator stands on one of the tables. "He was bellowing so loud that snatches of his discourse reached my ears. Union…brother…Marx…capital…bread and butter…love. It was all Greek to me...It never enters your head...that your charity is a crime, an incentive to slavery, stultification and organized murder. Take a good look at their living corpse. You may say it’s his own fault."

The stripping away of life circumstances opens a broader, ethically founded politics in which proper relation between the self and others remains the central but irresolvable concern.

Lovett takes us on his journey from the inside. The drama is the failed desire for connection beyond the self.

What Beckett creates is the present as experienced by most humans, but not by literary figures. British novelist John Banville writes that Beckett is describing life as it is lived. "Lived life, not life in literature, has no plot, no narrative, no meaning, no characters and presents no symbols. It simply is."

Clearly it is a mistake to think of The End as the tale of an old, decrepit, dying man.

At the conclusion of the play, Lovett stands tall, with his hands straight by his sides. He simply is; magnificent, both he and Beckett. The director has them both glowing on the stage.