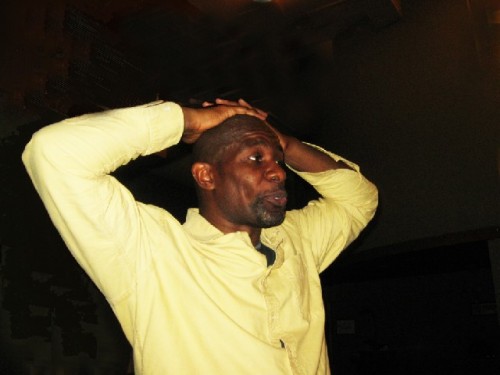

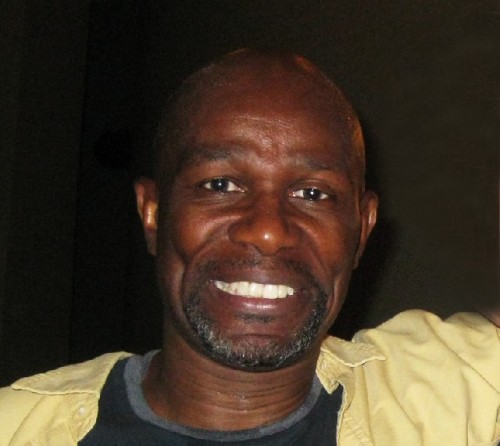

John Douglas Thompson Riveting in The Emperor Jones

Hit Show Moves to Soho Playhouse to Jan. 31

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 06, 2009

The Emperor Jones

By Eugene O'Neill

Directed by Ciaran O'Reilly; Choreography by Barry McNabb; Sets by Charlie Corcoran; Costumes by Antonia Ford-Roberts; Lighting by Brian Nason; Music and Sound by Ryan Rumery and Christian Frederickson; Puppet and Mask design by Bob Flanagan; Dialect Coach, Stephen Gabis; Production Stage Manager, Pamela Brusoski. Presented by the Irish Repertory Theater, Charlotte Moore, Artistic Director; Mr. O'Reilly, Producing Director. At the Irish Repertory, 132 West 22nd Street, Chelsea; (212) 727-2737. Through Nov. 29. Running time: 1 hour 20 minutes.

Cast: John Douglas Thompson (Brutus Jones), Michael Akil Davis (Ensemble/Crocodile God), Jon Deliz (Ensemble/Dandy), Rick Foucheux (Henry Smithers), Sameerah Luqmaan-Harris (Old Native Woman/Ensemble), David Heron (Lem/Ensemble) and Sinclair Mitchell (Ensemble/Witch Doctor).

It's the kind of performance—intelligent and internal but rapturously spontaneous—that benefits from a tiny theater (Jones transfers this week to the SoHo Playhouse, with its whopping 199 seats). Broadway traded some of its bombast for character-driven drama this year, but nowhere in New York was the art of acting on better display than the modest stages dominated by Thompson. "I've always felt that theater is a medium of language," he says. "You see man's relationship to language and to himself much more clearly when you strip things away."

New York Magazine, December 13

Link to Soho Playhouse Special run December 15 to January 31.

It has been a week since we saw the shattering and disturbing production of Eugene O'Neill's The Emperor Jones, starring John Douglas Thompson, at the Irish Repertory Theater, Off Broadway in New York. Since then the character, context, and issues of the rarely presented play, which was first staged in 1920, have inhabited and haunted me. They have penetrated into heart and mind, rattled my bones. Much like the nightmare jungle sequence of the play that serves as an allegory for Conrad's The Heart of Darkness or the collective unconscious of Jung; both of which were sources of inspiration for the playwright.

This is not an easy evening of theatre as the audience is assaulted and challenged. The former railroad porter, murderer, and escaped chain gang convict, Brutus Jones, through pluck, force and legerdemain has insinuated himself as the Emperor of a Banana Republic. He is as raw and primal as a gaping wound. While Jones is primitive and uneducated,

speaking in the dialect of a lower class negro of the period, we are presented with a man possessed of an evil genius powered by greed and self interest. What he lacks in nuance and education is countermanded by intuition and criminal cunning.

The persona has been hammered out, beaten into him, on an anvil pounded by class, abuse, the legacy of slavery, and repression. There is a pent up psychic energy that just exploded and focused him in the game and con that, for a time, elevated him as a violent and hateful tyrant. There are layers of irony as he speaks of his serendipitous stint of Emperor as a "job." It is only meant to be temporary and when, predictably, things fall apart, he has an escape path through the jungle and on to the French ship.

He will sail away to the fat bank account that he has stashed. Along the way are caches of food buried as he rehearsed the escape while simulating hunting in the jungle. By day he knows it well, but in a devolving endgame, it becomes unfamiliar and horrific by night.

Until this superb production, conceived and directed by Ciaran O'Reilly, the O'Neill play was largely viewed as dated, minor, embarrassing, stereotyped, and undoable. With absolute clarity, precision, and insight, sticking to the chapter and verse of the original script and stage directions, this work has been restored to its rightful position in modernist American theatre.

Because the content, premise, and persona of the play are so primal, arguably a snap shot of a time and thinking from which we have greatly progressed, the approach of rare productions has been to deconstruct or present the play with an angle and agenda.

It is a great tribute to O'Reilly, his cast, and creative team that they opted to play it absolutely straight. But also to give it the power of a staging that, although presented in an intimate theatre, benefits from a full range of production values. The set designed by Charlie Corcoran is simple but clever. It takes us from a first scene in the throne room of the palace into the ominous jungle.

The subdued but precise lighting of Brian Nason takes us through that jungle. It is clever when Jones looks for, but cannot find, his buried food. This is conveyed by spots of light that appear and vanish on the ground. They work to accelerate the downward spiral of the fugitive emperor.

As he stumbles along the escape route toward the sea and salvation there is the maddening sound, drums and music (Ryan Rumery and Christian Frederickson) of the pursuers. Of course, this is a familiar device but done here effectively.

While Jones negotiates a maze through the heart of darkness, descending ever deeper into mayhem and madness, the jungle comes alive. There is the animism of psychosis as the trees, roots, and vines attack and impede him. This is conveyed through elaborate choreography by Barry McNabb. It entails complex movement between Thompson and several actors simulating trees.

The costumes by Antonia Ford-Roberts, including those trees, play a vital role in the drama. Jones is dressed in the ersatz, paramilitary trappings of a general. Again, it is the familiar imagery of Third World oppressors. But in the jungle signifiers of rank smother and stifle him. In a fit of frustration and rage he throws off what has become a "strait jacket." He pulls off the boots that pinch and hurt his feet.

The most stunning and powerful device in this production is the evocative use of puppets and masks designed by Bob Flanagan. In his descent into chaos Jones is confronted by the specters of his past murders including smashing the skull of a prison guard to make his escape. O'Neill also evoked the collective unconscious, the embedded destruction that crosses generations, by conveying through the puppets images of slave markets.

Through these dramatic devices we come to learn what forged the psyche of the Emperor Jones and catapulted him into an oppressive reign of terror over what he denigrated as "ignorant bush niggers." The O'Neill drama does not exonerate his protagonist. We are stunned, shocked and riveted by Jones. We do not view him as a hero. In the end he gets what he deserves. But, as the audience, so do we. If anything O'Neill insinuates that we are complicit in his guilt and crimes.His decline and fall are a metaphor for our legacy of slavery, and, in this instance, colonialism. The implied message is that what goes around comes around.

Of course, this is hardly a theme that people flock to. It is a hard sell to have us look deep and hard into our horrific history of slavery, racism, and genocide. O'Neill allows us the escape hatch and easy out that Jones is a bad man who got what he deserved. He is also our Frankenstein. We made him who and what he is. It was what had me squirming at the edge of my seat.

It is also why the play has garnered rave reviews. I read some, however, that played into the old line. It was disturbing that critics can be so narrow and reactionary. For all of us this work is a challenge and learning curve. It is heartening to report that the run of the sold out show has been extended through December 6. Beg, borrow or steal to see this epochal, iconic production.

As we predicted last summer, when Thompson was still agonizing about playing the role, this production has proved to be a personal triumph for a brilliant actor in a truly stunning production. It is a remarkable highlight of the New York theatre season and likely to be recognized during the annual awards. Thompson previously won an Obie for Othello.

That play originated at Shakespeare & Company. In addition to his Othello we saw him last summer in Shanley's The Dreamer Examines His Pillow. Based on these three plays we regard him as one of the finest, yet to be fully recognized, actors of his generation. Of the three plays we have reviewed this is his most demanding performance. It is a very physical role in which he is tossed about in the jungle. There is also the complexity of period dialect with its uneasy cadence and syntax. His thorough training in Shakespeare allows him to master the patois. But there is not the familiar lyricism of Shakespeare. In that sense, the lines in O'Neill are far more demanding to learn and convey with conviction. He worked with the dialect coach, Stephen Gabis.

The personal triumph of this performance is how Thompson makes his Jones utterly real and believable. This is conveyed from the very first moments of a scene with his partner in crime, the white man, Smithers (Rick Foucheux). They despise but need each other sharing the motive of greed and ruthlessness. Smithers, as magnificently performed by Foucheux, has nothing but contempt for Jones. He views the emperor as a means to an end. But through excess Jones became expendable. The people have turned against him. Using his pistol Jones threatens to blow Smithers away but concludes that he is still useful.

They meet in the morning when the palace is deserted. The retainers and servants have all fled. They start to hear the drums. The horses are gone but Jones exudes confidence in his escape plan. Toting the revolver he spins the barrel and extracts the final, silver bullet. Part of his legend is that only a silver bullet can kill him. Should the worst happen he is saving this for himself. He understands the consequence of being taken alive. It is intriguing that he considers his own assassination.

Like many, I approached this production with skepticism. I read the play years ago during a commitment to read most of O'Neill's plays. This past year, we viewed the Paul Robeson film. How could any actor hope to fill those shoes? But the film, with its prequel as a porter and criminal, the literalism in the jungle scenes, seemed daunting if not impossible. The film is an icon but also a signifier of another time. It was also the first time that a role was specifically written for a black actor. It was originally performed by the legendary actor Charles Sidney Gilpin. After a falling out it was handed over to Robeson for whom it was his greatest triumph.

In this production, and performance by Thompson, the character has been deracinated into an everyman. It emphasizes the universality and flawed humanity of his character. The play is a metaphor for a series of trials. The arc of that dialogue begins with the ancient epic Gilgamesh, and progresses through Dante's Divine Comedy. It has parallels to the vision quests of Native Americans. It anticipates the voyage up river to assassinate the deranged and brilliant Kurtz in Apocalypse Now. It makes us again recall Brando in the cult classic Burn.

How can one ignore that O'Neill named his character Brutus? Is that a reference to his primary trait of brutality? Or is it a connection to Brutus, the betrayer of Caesar? Referencing Dante it is Brutus, the ultimate sinner who, with Judas and Cassius, is frozen in the very bottom, the Ninth Circle of Hell. In that sense is Brutus Jones a betrayer of the people he was mandated to rule and lead?

When Jones flees into the jungle his revolver has six bullets. To discharge one betrays his position to the pursuers. But each bullet represents a vision, trial, and metaphor. Rather like the challenges of Gilgamesh or Dante's Circles of Hell. As the ghosts in the jungle evoke his crimes there is an Aristotelian reversal. He was humble and then exalted. Now, the once exalted has been humbled. Taken down, like Oedipus the King, by his tragic flaw, in this instance, greed, followed by fear.

There is a Southern Baptist tinge as he prays to the Lord for forgiveness. But is this yet another vestige of repression and imperialism; conjuring the Jesuits who traveled with the Conquistadors. Is the ersatz evoking of Christian redemption by Jones an aspect of Manifest Destiny?

There is much to consider in this fascinating play and its superb restaging. It made me toss and turn, threw me about the room, slamming into the walls that define and confine us. Writing this is an exorcism but I expect never to be free from the grasp of the Emperor Jones. Hopefully, it will be an enduring landmark and beacon as we find our way through the jungle of the psyche and our collective unconscious.

New York Times review.