Julianne Boyd of Barrington Stage: Three

Defining and Transgressing Boundaries

By: Julianne Boyd and Charles Giuliano - Nov 06, 2011

Charles Giuliano Do you read your reviews?

Julianne Boyd Of course I read the reviews. Not necessarily the day they come out. Especially if I’m still working on something. Or I’m about to work on something else. Of course I hear about them. The show isn’t doing that great. Maybe we should cut back on the ads. The actors mostly do not read the reviews. But now with Google if you type in Barrington and the name of the play probably a few more read it than say that they do.

CG This has become a standard question for me and I am very interested in the responses. In a certain sense it makes me feel bad that the people we write about say that they don’t read critics. We put passion and energy into it so it is hurtful to feel that the effort is ignored. Sometimes it feels like you are speaking directly to the actor or director about some aspect of the production that does or does not work in your opinion.

What is the relationship between the critic and those we write about? Like you and I as we speak? Are we friends, colleagues, or just a means for getting messages out to the reader and audience? Do you talk with me just because of a readership that I have? I wonder a lot about those issues and relationships.

What is the dynamic? What is the role of criticism? Is there a difference between reviews and criticism? I read a lot of reviews but not a lot of criticism. So I am tossing that out.

JB I don’t know because I try not to think about it. Do you know what I mean?

CG No. I don’t know what you mean.

JB In the Berkshires the same people who write the feature stories also write the reviews. In other places the feature writers are different from the critics. You certainly don’t have a relationship with those critics as you only see them at opening nights. In San Diego I would have a feature writer write up the show but then a critic would review the show.

When I came to the Berkshires I was very surprised that a critic who wrote a feature also reviewed the show. That’s a difference. But I think you do get to know the critics better here.

CG That’s not entirely true. Peter Bergman (Advocate, Berkshire Bright Focus) and Gail Burns (Gail Sez) do not do interviews and features.

JB That’s true.

CG I do. Larry Murray (Berkshire on Stage) and Jeffrey Borak (Berkshire Eagle) do. So there is more of a split.

JB I always think that more do.

CG Some critics take the position that they do not want to know you. That it will compromise the integrity and independence of their reviews.

JB How do you feel about it?

CG I consider the creator as the primary source. The approach is Socratic. I do not know about theatre but you do. Let us converse and I will come to know some of your wisdom. For me it’s a vital learning curve. Which, one hopes, makes me a better critic. My position is that I am learning and what we are doing is a part of an educational process which is shared with readers.

JB It’s a great group of people. Clever, creative people who put themselves on the line. Every day they’re in rehearsal. Every day they’re writing the play. Every day I’m in auditions or meetings with the designers. I think that would be exciting to be a part of. As a critic to get to know these people. Perhaps as a critic to get to know them too well and then to have to write a bad review. That I think is difficult. I can’t spend a lot of time thinking of what the critics think of me. I have to think of what will make this theatre work or not work.

CG Do you ever find a review that’s insightful?

JB Oh yes.

CG Perhaps there’s something I didn’t see?

JB Absolutely. And I’ve also often read a review and wondered was that critic at the show I just directed? What? They missed the main point. Oh my God. They missed it. Then you read another review that gets it right. You go that’s just not right the readership just shouldn’t be reading this. That doesn’t happen as much anymore. It used to happen.

CG As Mary Zimmerman (director of theatre and Met Opera) told me she is a frequent flyer. She does not presume to tell the pilot how to fly the plane. Similarly she resents critics who tell her how to direct her play. Do we have that right? Should a critic stop short of providing notes on how to improve a play?

JB You don’t have the right to tell us how to do our craft. I don’t think most critics do. Occasionally there can be a valid comment when I go aha. Often I go, what? Huh? Often they are bringing something to it which isn’t in the play. Do they have preconceived notions of me, the theatre, the actors, and the play? I think this is the most difficult part, Charles, of being in the theatre. You’re putting yourself up for criticism of every work you do.

My job is to direct plays. Every time I do people come in and criticize it. Whether favorably or not. If I’m a lawyer and lose a case in court it’s not going to be in the New York Times. It’s not going to be in your blog. It’s not going to be in the Berkshire Eagle. But if I do a play everyone feels they have the right to criticize it. If I were a blogger and I said something wrong the whole world isn’t going to know about it. If in the operating room the doctor makes a mistake yeah maybe that person will get sued. But maybe they won’t. There are very few jobs where you are openly criticized for the artistic beauty of your work. For the passion and compassion that you have.

I also know of certain actors when they get a negative review it just freezes them up. Or playwrights. For six months to a year they just loose the desire to write or act. That’s really sad. That somebody can write something so nasty that it affects someone in such a negative way. There has to be a better way to do critical analysis than to maim and paralyze someone. That happens occasionally. Not often anymore. It was probably much more vitriolic in the past.

CG There was an incident when the Washington Post panned a performance by Margaret Truman. The President wanted to storm in and punch out the critic. Or call down a nuclear strike on the Post. One thinks of the famous scene in Citizen Kane where he writes the nasty review of the critic, played by Joseph Cotton, who has passed out drunk after seeing Kane’s mistress in a terrible performance. Kane finishes the review as the critic would have written it. Really nasty. The review runs and Kane fires the critic. I think those kinds of dialogues go on and on.

JB There’s no easy answer. I think that artists are always vulnerable. I tell the actors bare your soul. Be honest as honest as you can be. Yes, that’s what I want. Then we all feel that we have created something. The audience seems to like it. Then you read the review and that person is ripped to shreds. We’ve just asked them to be open so you can understand why they close off for a period of time.

CG Not just critics, directors can do that too. Maria Schneider never did anything of significance after Last Tango in Paris. Even Brando described how Bertolucci aesthetically raped him during the making of that film. A director can demand so much that an actor in a sense never gets that back. When you get pushed so deeply into a difficult role or character how do you get back out? What does it take for actors to play those roles?

JB I think what Bertolucci did was denigrating. It happens more in film because actors are hungry to get those roles.

CG I don’t think we can assume that Brando was hungry for that role in Tango (or Apocalypse Now) and yet he submitted to being directed in those complex characters. There was a mutual respect and cooperation between the actor and the directors. It was a process of creating the work.

It is the kind of question that I often ask. Talking with Mark St. Germain, for example, how do you get into the head of writing dialogue for a Ku Klux Klansman? Then, at the end of the day, how do you get out and back to family life? Those transitions seem to be difficult and arguably some individuals get lost in the process. Does that start to break down aspects of our integrated personalities? Do we start to become fragmented? A collage of roles and personas?

JB You know Mark. I think the answer would be no. He writes the characters and then he closes the book. When he’s writing a play he’s researching another. So he keeps himself fresh. So he doesn’t become so obsessed with those characters that he is living their lives.

CG Have you ever gotten so deeply into something that it was tough to get back out?

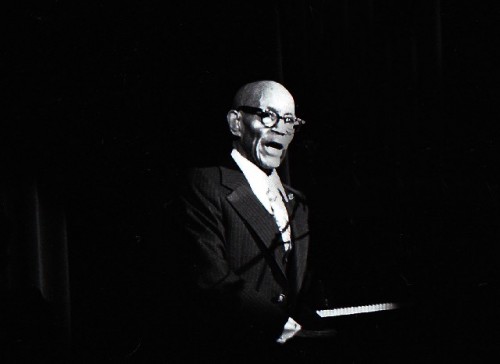

JB No because I have a family. At the end of the day I have a husband and three children. Now my kids are grown. But years ago when I was directing Eubie, which was out of town in Philadelphia and coming into New York, the producer was very difficult. (1978 production of Eubie!, a musical revue based on the works of Eubie Blake which she also conceived. The production starred Gregory Hines and Maurice Hines, and received three Tony Award nominations.) We need to do this change and that change. It was getting great reviews and doing fabulously. He would be calling me at two and three in the morning. What decision do I have to make at two that I can’t make at eight? He was overwhelming me. I couldn’t sleep through the night.

My son was four and my daughter was eight. My son the next day said to me “Mommy I’m the only kid in class who doesn’t have sneakers. You forgot to get me sneakers for gym class.” I took the train from Philly to New York. I felt, now that’s important. My child having sneakers is more important than a producer calling me at two in the morning to change a song which he could have asked me at eight in the morning. The show was set but the producer was nervous. So I was calming the producer. I thought, you know what? I have to keep track of what’s important. The important thing is my family. Yes the career but you have to have some sort of balance. If you don’t have a family it’s more difficult if you don’t have that balance. If you’re a single person living by yourself without a roommate or partner. Then it becomes more difficult.

Part One