Margaret Stein, Berkshire Artist

Two Retrospectives of Her Work

By: Susan Hall - Nov 08, 2011

Some artists dress up in their penguin suits every night and court patrons at parties. In New York it may not be a sure path to success, but you are not likely to be successful if you don’t frequently perform this ritual. This is true in Stockbridge too.

Margaret Stein, who died at 80 in February, always produced art. She didn’t give a fig for fame. Working in many forms, lithography, pastels, plywood cutouts and oil paint, she created a prodigious number of works that delight and provoke.

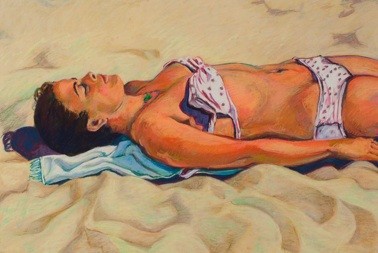

In a memorial retrospective at the Greenfield, Mass. Community College where she taught for over twenty years, and at the Dickinson Memorial Library in Northfield, almost a hundred of her works have been on display. Her daughter Jenny Stein curated the shows. Stein has wonderful portraits of all three of her daughters. One called “Elizabeth Sleeping” is the standout pastel with painterly effects, a beautifully rendered portrait of a young girl bathed in sunlight and casting shadows with rough hewn strokes capturing both subtle details and the bolder facets of the image.

A very sober and rough painting of football players in action gives a very different impression than the lithographs. Some prints are ‘found’ landscapes, which emerge from a chaotic background to achieve the various familiar forms of beach grass, trees and scrub. Stein’s charm and playfulness are evident in other lithographs. Bug Happiness, Cows, My Monster are favorites of mine.

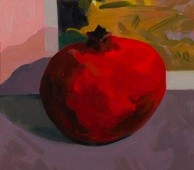

One wall is covered with 38 still lifes, the focus of Stein’s work for a decade. The lush red pomegranates leave you feeling you have never seen red before. Stein has a unique approach to mottling edges to create shape. One bottle that often appears grouped in still lifes was tiny in reality, but always adjusted in size to suit the painter’s purposes. Stein studied Morandi’s work, and, like him, felt that the size of a work in no way limited its power. In some ways, the fixed and controllable subjects were an ideal jumping off point for Stein’s pictorial experimentation.

Wayne Thiebaud is also quoted, but more often tucked in a corner than brought front and center. A cake is suggested at the frame’s edge in one of the more playful still lifes and marks in Kool-aid colors are displayed in another.

A nude Olympia figurine carved from plywood is in a 1:1 ratio to the famous Manet painting which caused a ruckus when it was first exhibited. Manet said at the time “the artist has to move with the times and paint what he sees.” Stein might well have announced this when she placed Olympia on the side of her home with no parental advisories. At the exhibit, Olympia is surrounded by several chickens and a rooster modeled on the real resident rooster, Pretty Boy Floyd.

Photographs at the Northfield library show are startlingly beautiful, framed as long horizontals, and creating a curiously delicate Japanese effect while packing a wallop.

Not all of Stein’s work is represented in these two shows. She also was a ceramicist, textile and graphic designer and created sets and lighting for local theater productions. A colleague of Stein’s, who taught and painted with her, imagines Margaret as a capacitor, an electronic device that stores power and then delivers it with a particular punch.

For Stein, making art was all and now that she is gone and her daughter is ready to launch her mother into public view, we will see how this prolific and fierce artist fares in the world of 21st Century art. She deserves attention.