Buckminster Fuller, 20th Century Visionary

Eccentric Genius Celebrated at Whitney and MOMA

By: Mark Favermann - Nov 09, 2008

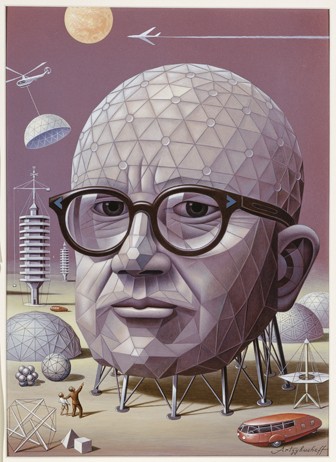

I only saw Buckminster Fuller in person once. In the late 1970s, at the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado, I walked into a lecture being given by this older, short, stocky, balding man with thick glasses. Coming up for air rarely, Fuller spoke in a non-stop stream of unworldly consciousness. He had a holistic, eccentric vision of the world. Hearing him drone on and on, I stayed for about 20 minutes.

Leaving, I was drawn to another, less crowded seminar that was going on at the same time. After my seminar was over, perhaps it was about aboriginal architecture or something just as esoteric, I walked by the first seminar hall. The verbose, very serious man was still talking on and on. Few people had left the hall. Perhaps, even a few more had joined. Fuller spoke for over four hours that day. Fidel Castro had nothing long-winded elocution-wise on him.

Buckminster Fuller was an American original. He was a stubborn but highly structured visionary. Born to a prominent New England family, in 1895, in Milton, Massachusetts, Fuller died in 1983. He was the grandnephew of the American Transcendentalist, Margaret Fuller. Supposedly, like Frank Lloyd Wright, as a small child, Buckminister attended a Froebelian kindergarten with its series of blocks and puzzles. As a boy, he worked on propulsion for model boats.

After attending Milton Academy, Fuller flunked out, or as he preferred to recall, was expelled from Harvard College twice for bad behavior (something about showgirls in his dorm room). He served in the Navy during WW I, worked as a meat packer, and seriously contemplated suicide before reinventing himself. This process included creating himself as an engineer, inventor, philosopher, lecturer, architect, techno-nerd, and even a poet.

Considered by many to be a visionary inventor, rather than an architect or a designer, Fuller's work was full of extensively described rationale and carefully crafted symbolism. His massive explanations confounded and confused many who were exposed to them. Eccentrically, he invented his own terms and definitions for concepts and theories. Fuller spent many hours a day documenting his thoughts in voluminous diary notebooks. He was obsessed. Yet, his was a unique vision.

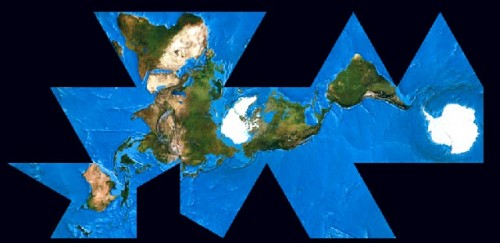

Fuller devoted most of a long professional life to the convergence of science and technology with the humanities. He was an interdisciplinary thinker, one who integrated rather than separated systems, theories of science, technology and the arts. Admirably, he attempted to create a comprehensive world view. He saw the world as having structures and systems that explained how everything worked and how new technology could be developed and properly used. Coupled with this, Fuller wanted to develop design solutions that affected the greatest number of people in the most positive ways.

Early on, Fuller's concepts focused upon environmental conservation, affordable efficient housing, and global distribution of information. His approach was highly aesthetic as well. Good design meant elegance to him. Many of his closest friends and supporters were artists. Not surprisingly, his work influenced many artists, architects and designers. Because of his early environmental concerns, today his work has a special resonance.

Last summer, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City presented a major retrospective Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe. This provocative exhibition was accompanied by a book and a series of events around New York City. These were to commemorate and celebrate Fuller's life. The show coincided with the anniversary of Buckminister Fuller's death 25 years ago. In addition, the first annual Buckminster Fuller Challenge awarded $100,000 to fund a proposal to turn Appalachia into a sustainable community.

Reviewing his entire career, there seems to a mix of good, even great ideas and bad, no terrible idea applications. Some of his ideas now seem a bit dangerous and strategically naïve. His three-wheeled Dymaxion Car shuddered from side to side. Fuller's concept for an Instant Slum Clearance Project envisioned plunking down 15 "Skyrise" towers (resembling nuclear power plants) in the back alleys of Harlem. Notoriously, his signature Geodesic Dome, when built on large scale, leaked badly. The best use of geodesic domes was for children's play equipment. Even so, a lot of Fuller's thinking was way ahead of its time.

Decades before Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth, Bucky Fuller searched for ways to protect "Spaceship Earth." He was an early environmentalist and advocate for sustainability. His personal and professional mantra was doing more with less. His World Resources Inventory was three decades ahead of anything award-winning architect and Green theorist, Bill McDonough, has proposed for sustainable building systems. Extremely prescient was Fuller's maxim that "Pollution is nothing but the resources we are not harvesting." The eccentric guy did have some great ideas.

Fuller certainly had his detractors. His attitudes and self-convinced demeanor turned-off a lot of establishment types. In fact, as an organization, the American Institute of Architects completely dismissed his idea for mass-produced, prefabricated dwellings. They even passed a national resolution: "The American Institute of Architects establishes itself on record as inherently opposed to any peas-in-a-pod-like reproducible designs." The very-connected architect, Philip Johnson, called Fuller a "lousy architect." Architect Peter Eisenman said "He was a tinkerer who took great stuff and turned it into shit." But tell us what you really think Peter.

Yet, there is a certain anti-establishment Buck Rogers quality to his visionary designs. His vision was futuristic, streamlined and often quite celebratory and joyful. At a very thoughtful and brilliant encyclopedic exhibition that closed at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in mid-October, Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling, Fuller's drawings, diagrams and scale models showed well against more conventional architects' designs. Though appearing a bit stylistically dated, his work held up well against other historic visionary work by architects Peter Cook and David Greene of the 1960s Archigram group and Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius at the 1920s and 30s Bauhaus.

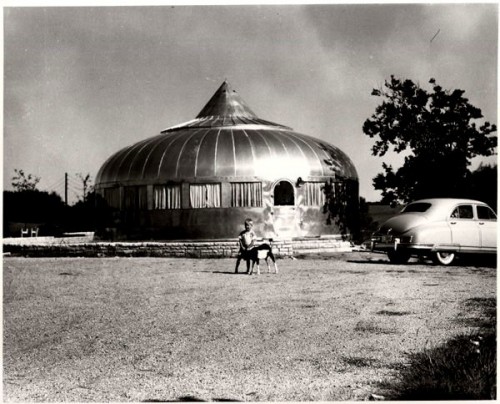

The Dymaxion House is a case in point. Fuller began theorizing about the house in 1927. It along with his Geodesic Dome are his two most influential design concepts. Fuller aspired to improve upon contemporary homebuilding methods by creating a house that could be fabricated by machines. Pieces would be modular and fit together easily and efficiently. Homebuilding would not require an architect or builder, but instead would be the product of the expanding global industrial economy. Only three prototypes were ever produced. Two were never lived in while one was occupied by members of his family through the 1970s.

Perhaps the last word about Buckminster Fuller should go to Harvard Graduate School of Design professor, Michael Hays, the co-curator of the Whitney exhibition. Hays studied architecture in the 1980s. He states, "We were the generation that said everything is fragmented, that there's no such thing as a whole. But Fuller still insisted on thinking about total systems." We certainly need to think and act that way today.