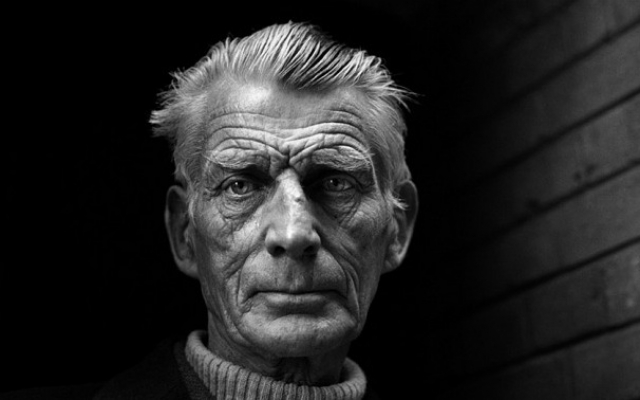

White Lights Festival Presents All That Fall

Beckett's Radio Drama Re-imagined

By: Susan Hall - Nov 10, 2016

All That Fall

By Samuel Beckett

Pan Pan Theatre

Gavin Quinn, Director

Aedín Cosgrove, Set and Lighting Designer

Jimmy Eadie, Sound Designer

Voices:

Áine Ní Mhuirí, Mrs. Rooney

Phelim Drew, Christy

Daniel Reardon, Mr. Tyler

David Pearse, Mr. Slocum

Robbie O’Connor, Tommy

John Kavanagh, Mr. Barrell

Judith Roddy, Miss Fitt

Nell Klemen, Dolly

Andrew Bennett, Mr. Rooney

Joey O’Sullivan, Jerry

Duke Theater

White Light Festival, Lincoln Center

New York, New York

November 9-12

The Pan Pan Theatre takes Samuel Beckett’s intent seriously. The setting of this radio drama evokes a living room in which you sit in a rocking chair, going to and fro. The room starts pitch black and then 120 evenly organized headlights look out at you. They will change as the story we hear unfolds.

Above us are the delicately hanging lamps, perhaps of the train station. Maddy Rooney, spoken by Áine Ní Mhuiríani, who sounds like Molly Bloom here, is trudging down the road to the station to meet her husband’s train and trudging back with him along a ditch to save about 5 pence. It may be his birthday. Or it may not. We are suspended in time in our living rooms.

Before we hear a snippet of Franz Schubert’s Death and the Maiden, we hear the sound of country animals. Beckett never wanted to flaunt his learning, but wished to show how common he could be. The Edison label published Old Macdonald Had a Farm in 1925. It was a worldwide hit. Beckett, the absorbing polymath, probably picked up the song along with Gilbert and Sullivan and Franz Schubert. Beckett played the piano and went to live music concerts often. Now the music of the song is stripped away and so are the words. We are left with sounds. Even in Happy Days, humans are submerged in sand, barely there.

Yet Beckett wanted his language flattened, which sets it off in a blaze. In All That Fall, in his leading lady Maddy, suddenly we have a tone poem in brogue. Vowels and consonants are harmonious. We revel in alliteration and the mood of exaltation.

Maddy rises above the dung to sit in the back seat of Mr. Slocum’s car. As she is hoisted up, we imagine a sexual scene. The erotic tone of the lift, and generic words like ‘stiff’ are used to suggest sex. Like Shakespeare, sex and violence are central to Beckett and his language pictures them in the mind’s eye.

There is pleasure in the word play, in the pulsating rhythms. Suddenly we hear no longer the voice of a woman, but waves beating on the shore.

Like a three movement chamber piece, each section ends in a darkness neither as black as the opening, nor as black as the end.

Beckett was acutely aware of the form in which his work was presented. Radio plays were not intended to be fleshed out with characters, who exist only in the mind’s eye.

Productions of some radio plays have blindfolded the audience. Here eyes are wide shut. The loud and sometimes frightening approach of the train is done with blazing headlights, so intense that you are forced to turn from the scene in front of you. We are in a moment like the Schubert quartet, where the composer rages against death.

Death is near but we are begging it to give us more time. Beckett liked to quote the poet Vincent Volture who wrote, "Death never thought on me, who never thought of her."

Voices of the actors, and the suggestive sound effects are more than enough to make this unusual Beckett, which features his only female lead character, both juicy and distant. We are tranported by Pan Pan and its actors into a defiant celebration of life, haunted by the end. Beckett's wings hover above us.