Abstract Expressionist Arshile Gorky

Exploring Boston/ Watertown Armenian Heritage

By: Martin Mugar - Nov 11, 2014

In the mid-Nineties Armenian art historian Levon Chooksazian was asked by a German publishing house to write short biographies of Armenian artists of the 20th century for inclusion in a world lexicon of artists. Because I am an artist of Armenian descent, he contacted me to learn about my history and those of other Armenian/American artists whom I knew. One artist that he had already heard about was my great uncle Marvin Julian.

Since he was someone, whose story was part of family lore, I was able to fill in lots of details about his life. Levon always enjoyed coming to Boston from Armenia to lecture, and, moreover, as a lover of the Armenian language, to hear the dialect of Western Armenian still spoken by the nonagenarians, who came from Western Anatolia around the beginning of the last century. With the passing of that generation and the extirpation of their ancestors in the towns of central Turkey such as Harput, this dialect is now disappearing. Such is the lot of the Armenians. Their moments of political coherence are short lived. Levon always goes about his work with a sense of urgency to document the actors and players in Armenian culture, while there is still an Armenia in which Armenian culture can thrive.

If it were not for the persecution of Armenians in Turkey, Marvin Julian, born Chooljian,(alternate spellings from his early years in America are Chooljean and Chovilijean) would not have come to this country. The Ottoman overlord's pogroms on the Armenian minority, periodically, reminded them of their inferior social position and confiscated their money in a rude sort of taxation. My grandmother, Marvin’s sister, said that during these assaults the young boys were rolled up in oriental rugs to hide them from the soldiers. When the dust settled on one of these sporadic attacks, my grandmother, just a little girl, wandering the streets with her mother inquired why there were so many people sleeping in the street.

It is out of and from this turmoil that Marvin and his extended family came to Boston. I have always marveled to what degree, originating from the rural interior of Anatolia, he was able to sort out the cultural reality of New England in short order, so as to eventually establish himself as an artist of no mean repute in the city of Boston.

Piecing together his early years leaves much that is out of focus. He enlisted in the American Army before World War, but never went to war, remaining at Fort Devens outside of Boston. He survived the notorious influenza epidemic in 1918 that killed more American soldiers than died on the Front. My father remembers being so proud to see him in uniform in Boston, when the American Army replaced the police, who went on strike in 1919. It was probably prior to his service in the Army that he met John Singer Sargent, who worked on the Boston Public Library murals up until 1919. He would run errands for him such as buying a newspaper and would receive art instruction in exchange.

The story was already part of his resume in the 1930s article on him in a Boston newspaper. By the early Twenties he moved to Paris to study at the Academie Julian, a haven for American artists, which functioned as an avant-garde alternative to the L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts. It trained not only the French Modernist Matisse but Americans of note such as Sargent, Henri and Prendergast. He made money as a gravedigger in the American military cemeteries of the Great War, and frequented Sunday salons organized by wealthy Boston matrons living in Paris. His father who worked like many Armenians in the Hood Rubber Plant in Watertown, Massachusetts, just outside of Boston, helped him out financially, until some monetary setbacks made it impossible to continue his support.He was forced to return to Boston. The story goes that in despair he threw all his art materials into the Seine.

His life in Paris was brought into focus several years ago, when I went on a tour with my wife on the Left Bank of Paris to locate the school, where she had studied before going to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. When we found the school and entered the courtyard I noticed inscribed above a door: "Academie Julian". Was this once the location of this famous school that my great uncle took his name from? The school was on break, so that our presence in the school was noticed by the school’s director. We addressed our questions to him and learned that indeed this had been the famous Academy, before it became in the 1950's the preparatory school for the Beaux-Arts that my wife attended.

When I told him of my uncle, he said that there would be a record of his attendance and that in fact the vice-director of the school was writing a book about the history of the Academy. The vice-director was in his office and spent sometime with us looking up Marvin’s name. Indeed his name was on the list of students and he had also won an award for his painting.

Back in Boston with Academy Julian credentials under his belt, he became a teacher in several art schools. We are in possession of a catalogue from The Exeter School of Art that lists him as an instructor. Several anecdotes that he related to me of his early years in Boston concerned his relationship with Arshile Gorky, who lived in Watertown with his sister for several years on Dexter Ave, where Marvin’s parents lived. Marvin, who was born in 1894, was ten years older than Arshile.

Marvin said that Gorky studied art under him at The New School of Design and Illustration, which the Gorky Foundation lists as the school he attended and eventually taught at. In a discussion with the director of the Gorky Foundation I was told that they are going to research more thoroughly his life in Boston and hopefully turn up class lists that would confirm his relation to Marvin. Marvin described Gorky as a larger than life character, who would dazzle his fellow classmates with his ability to draw perfect circles free hand. At that time, Arshile painted in a tonal style similar to what was popular in Boston and a style that Marvin never strayed from.

Gorky moved to New York and began his transformation into a Modernist, absorbing Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso and Miro. My uncle attended Gorky’s first opening in New York City. He recalls being snubbed by Gorky at the opening, who Marvin wrongly thought was embarrassed to show his old teacher what must have appeared to Marvin, the student of Sargent, as crudely wrought images. I have always contended that Gorky was embarrassed by his former teacher, who appeared to him as a representative of the old guard. In the end neither interpretation is accurate.

The answer to this interaction between Marvin and Gorky, only became clear to me upon seeing Cosima Spender’s documentary on her grandfather: ”Without Gorky”. It depicts in the words of his wife, still alive, and his two daughters, the oppressive shadow that this inspired genius cast on their lives. It was not at all flattering of the great Armenian Painter. One aspect of Gorky’s life was spelled out emphatically in the film: he was very intent on maintaining the myth of being the son of Maxim Gorky. So much so, that his wife only learned of his Armenian heritage toward the end of their life together from a grocer in Sherman Ct.. Obviously, Marvin knew Gorky was Armenian and his presence at the opening, risked blowing Gorky’s carefully constructed cover as the son of Maxim Gorky. Hence the snub.

His resume at the Grand Central Art School that I read on the Gorky Foundation website says that he studied at the Academie Julian under Jean-Paul Lauren. The Gorky Foundation admits that this is totally fabricated by Gorky to plump up his resume and in my opinion is taken from his teacher Marvin at the New School of Design and Illustration.

According the Gerard Vallin, who is writing a history of the school, Lauren was a teacher at the Academy Julian when Marvin was there.

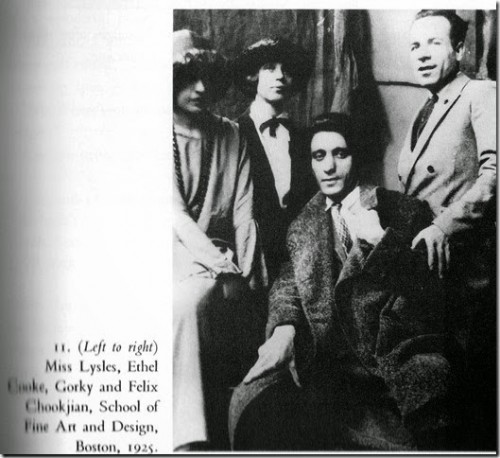

There is a good deal of circumstantial evidence to support the relationship of Gorky and Julian. The most intriguing is a photo that is an iconic part of the Gorky memorabilia, which appears in several biographies of Gorky. It portrays the young Gorky in 1925 at The New School of Design and Illustration in Boston, looking princely with a fur coat seated next to two women (one identified as an instructor Ethel Cooke) on his right and an artist to his left named Felix Chooligian in one biography(Mooradian) and Felix Chookjian in another.(Herrera) A recent search by my sister on the Ancestry.com has uncovered a passport request from Marvin Chooljian to study in France with a letter of support from the New School of Illustration and Design's director Douglas Connah, which describes him as a student of said school.

The date is 1920. He came back from Paris in 1922 and presumably started teaching there, where as Marvin claimed, he had Gorky as a student. There is also a photo of Marvin from 1925 that was in the possession of Marvin’s sister (my grandmother) wearing what appears to be the same suit worn by Felix in the photo of Gorky. I have shown numerous people the two photos side by side and no one has doubted that Felix is Marvin. The difference in spelling of the last name does in no way discount my theory that the Gorky photo is of Marvin as Armenian names were transcribed phonetically and were subject to various spellings.

The only fly in the ointment is that the first name Felix is not one I have ever heard attributed to Marvin and also in the Mooradian biography he is referred to as a Vanetzi, i.e. born in the province of Van, Gorky’s birthplace, whereas my great uncle was Harpetzi. The director of the Gorky Foundation Melissa Kerr said that Karlen Mooradian, Gorky’s nephew, who labeled the photo, tended in his writings to mythologize about Gorky’s Armenian roots and would have found it supportive of the myth to have Felix be a fellow Vanetzi. All that is left for me to find to confirm the connection of Gorky would to find evidence of Marvin's role as a teacher at the New School.

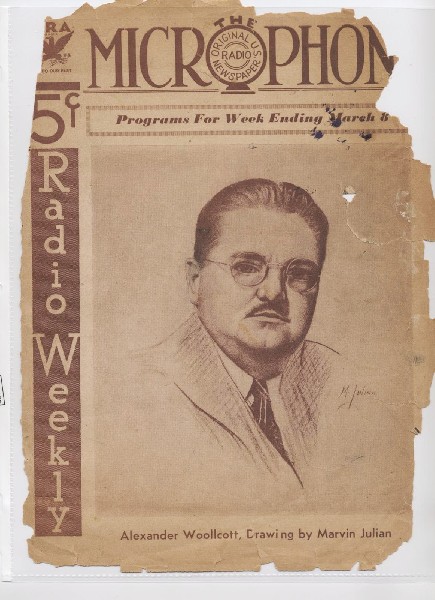

In the thirties he taught magazine illustration at the Exeter School of Art in Boston’s Back Bay. Among several examples of magazine covers he did for Microphone, a journal of radio topics, there is well- known critic Alexander Woollcott.

Marvin was already in his sixties, when I was old enough to remember his presence at family get-togethers. He lived a bohemian life in a sparsely decorated studio at 110 Newbury St in Boston’s Back Bay with his mother. He was seemingly able to subsist on a diet of coffee and cigarettes. He often said that if he were ever to be burglarized, the robbers shocked at his poverty, might be compelled to leave something for him.

I recall that he had no refrigerator and kept the milk for his coffee out on the balcony in winter. On occasion our family would visit him and his mother on a Sunday bringing with us a meal of chicken and pilaf. I recall his window shades were attached to the bottom of his windows and lifted up from there to keep the north light always lighting from above. Over the years, I learned bits and pieces of about his life in Boston and Paris, but there is much he kept to himself. I asked him once about the “Bal des QuatZ-Arts” in Paris that was a notorious Saturnalia, where participants typically dressed up or rather undressed as classical Greek sculptures. He admitted attending but was unwilling to talk about the details and said ”Mum’s the word.” He displayed the same diffidence in the Boston newspaper article (above) about the details of his relation to Sargent.

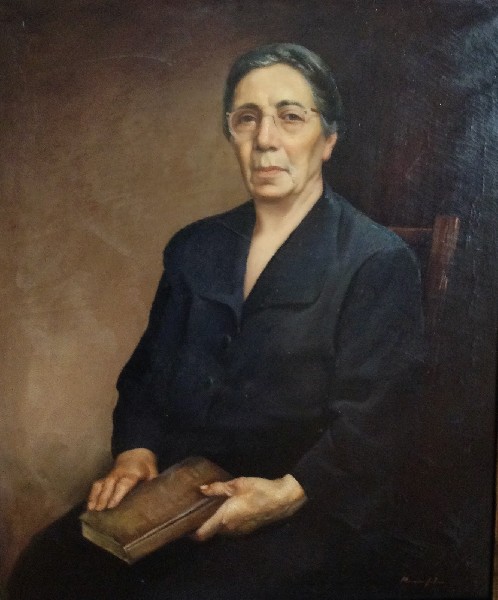

Stylistically his best portraits showed the influence of the Ashcan school, especially when he was free from having to flatter the subject, as in his portraits of his parents. On Askart, a site that lists artist's auction history, he is noted for “floral still lives”. Indeed, our immediate family is in possession of many of them. To my eye it is in these works that the aesthetic of Marvin shines. Each bloom is delicately and never generically observed. There is a feeling of tenderness for each bloom, which must be cherished and not harmed. Although his work may be lacking in any dialogue with the dozens of “isms” that ruled the 20thc and remained within the language of chiaroscuro, which he learned from his idol Sargent, there is a sensitivity to presence. It just sings out the fragility and nuance of the moment, the exact instant of apperception.

My father told me, which was typical of his pessimistic reminders of the fickle nature of the economy that the Exeter School of Art closed down during the Depression. The next evidence of Marvin’s presence in Boston comes in the late 30’s, when he was commissioned through the Federal Arts Project to do a portrait of an admiral for the Naval War College. From then on, he became well known as a portraitist in the Boston artistic community. There is an article about a portrait that he did the early Sixties of the wife of then Governor of Massachusetts, Foster Furcolo. Within the family he was, as it were, the court painter, doing pastels of his nieces and nephews.

He spent his later years alone in his apartment on Newbury St. His second home was the Boston Public Library, where he read copiously in classical literature. I once noticed him reading Rousseau’s “Confessions”. He must have been somewhat bewildered by the evolution of the art scene in Boston, which in the Fifties was very much defined by the Boston Expressionists.

They complained that the explosion of Abstract Art in New York, which they felt was too French and immoral, had sidelined them. I can imagine that Marvin and his devotion to the art of the 19thc felt even more out of place. Interestingly enough my teaching career in Boston began two years after his death in 1988 at an art college just up the street from where he taught, as though in some strange notion of karma I had to fill in for his absence from the Boston art world. I had moved to France as he did and spent a commensurate amount of time there. When I came back in the late 70's and showed the work I had done there at the Bromfield Gallery he came to the opening and quietly advised gallery goers what to purchase. Presence has haunted Western Art and philosophy since the time of the Greeks. And for several centuries the notion of beauty grounded in disinterestedness also reined. It clearly was the underlying principal of all of Marvin’s thinking about painting.

Recently, I came across an inquiry about Marvin on “Askart” by someone one who knew him in the late 70’, early 80’s. Marvin would have been in his mid 80’s at the time. I replied to the email, which was already sitting on the site four years and got this reply, which sums up better than I could the last years of an independent artist who always followed his muse.

Hello,

I received, with pleasure, your email regarding Marvin Julian. How did you come by my name? I am surprised, since it was so many years ago that I had met Mr. Julian (as we all referred to him). I was his neighbor in an apartment on Newbury Street, back in the late 1970's/early 1980's. I used to take care of him; visit with him, fetch groceries sometimes, make sure he was okay in the cold. At the time I believed he was one step away from being homeless, and it broke my heart. As you say, he was extremely private and would not talk about much, except his painting. I can still picture his apartment, and smell it…..it had the strong smell of paint and linseed oil. It was like stepping in to another world, another era. His apartment was always cold in the winter, too cold for an old man with failing eyesight. He often wore a sort of blanket/shawl over his shoulders. *I made him hot drinks, kept him company.

One day he said he would paint me, and I was thrilled and bewildered. I didn't know what to expect. But I knew it was important to him, as his sight failed, and he needed to paint. And, I think, it was his way of saying 'thank you' to me, although he didn't need to, as far as I was concerned. To me he was a great man, mysterious, mercurial, but clearly brilliant. In his almost empty apartment (he insisted, one day, that I should take the area rug, something someone must have given him) he had two amazing portraits on the otherwise empty and dirty walls. One, which I was awestruck by, was his mother; dark and serious and very formal (I'm sure you know it). So, I sat for him, and very quickly he had a painting which I think captured me so well. I look at it now and find it funny and glorious, as who would not! I'm a young man sitting there, trying to look formal and serious myself, long 1970ish hair, wearing a formal tie and sport coat. I thought I should look the part for Mr. Julian.

I moved house after two years there, and lost touch with Mr. Julian. Although I think he enjoyed my company, he was closed tight, didn't really know how to relate very well, and seemed, so sadly, to be alone and lost in the world and, frankly, waiting out his remaining time. I have always remembered him, always think kindly of him, always will.

Mr. Julian told me that the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. has some of his paintings, do you know if that is the case? I would so love to see more of his work. John Singer Sergeant (sic) has always been my favorite painter, and I see the strong influence in Mr. Julian's work. I've always felt he should be celebrated more for his incredible work, do you know where his paintings are located, museums etc.?

Thank you so much for your email, and I wish you well,

Tomas C. Jonsson

*When I shared this letter with a cousin whose mother was very close to Marvin, they were somewhat taken aback by the grim image of Marvin's last days portrayed by Mr. Jonsson. They periodically visited him to clean his apartment and replace items which were old and frayed with newer ones. My aunt suggested that the rug he gave to Mr. Jonsson was one that she had given him. Marvin enjoyed the concern of an extended family, who were equally enthralled by this most enigmatic of artists, but proudly portrayed himself as an independent artist to my Jonsson.

Reposted with permission from Martin Mugar's blog Painting.