The Getty Center Cost $1.3 Billion

Destination for 1.3 Million Annual Visitors

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 14, 2014

Admission to California's Getty Center is free but there is a $15 parking fee. On the Sunday afternoon in early November when we visited it took some driving about to find an empty space.

Perched on a cliff the Richard Meier designed complex, which opened in 1997 at a cost of some $1.3 billion, is not readily visible from below.

From the three car tram that conveys visitors to the complex one catches brief, tantalizing glimpses of the travertine marble veneered exterior walls.

The use of white titled exteriors has been a standard in Meier’s architecture since the High Museum of Art earned him the Pritzker Prize, the most prestigious in the field, in 1984. The museum was built for just less than $30 million. I recall it as seeming small when first visited not long after it opened. The museum at that time lacked a significant collection so the design was more impressive than what was dispayed.

We had a different impression a couple of years ago with an expanded collection and superb special exhibition of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

In 2002, three new buildings designed by Renzo Piano more than doubled the High’s capacity to 312,000 square feet at a cost of $124 million. The Piano buildings were designed as part of an overall upgrade of the entire Woodruff Arts Center complex. All three new buildings erected as part of the expansion are clad in panels of aluminum to align with Meier’s original choice of a white enamel façade.

While massive and gleaming with bright California sun reflecting that expanse of white marble, overall, the design by contemporary standards looks dated and conservative. It is more cohesive than trendy museum and arts buildings designed by Frank Gehry.

Although trustees and building committees strive for spectacular architecture what is impressive today too soon becomes a dated cliché. Meier’s 2002 Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art failed to impress during two visits. By then the signature white exterior was bland and generic.

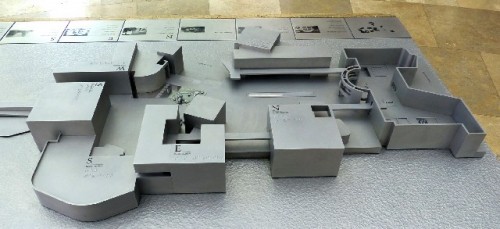

It is difficult fully to absorb the visual impact of the Getty Center. We are discharged into it facing a monumental staircase with sculpture platforms as we ascend to a plaza flanked by several free standing buildings. There is no way to step back and get a comprehensive, panoramic view.

The Getty is multi functional and galleries of permanent collection and special exhibition space are just a part of the mandate. The campus also houses the Getty Research Institute (GRI), the Getty Conservation Institute, the Getty Foundation, and the J. Paul Getty Trust.

In addition to the Getty Center there is also the older Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades. The original structure with more limited capacity for visitation houses the ancient Greek and Roman collections.

Widely viewed as the world’s wealthiest fine arts trust it has ebbed and flowed with the global economy. The Getty Trust experienced financial difficulties in 2008 and 2009 and cut 205 of 1,487 budgeted staff positions to reduce expenses. Although the Getty Trust endowment reached $6.4 billion in 2007, it dropped to $4.5 billion in 2009.

There was a New England connection when John Walsh left the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, where he was curator of European Art, to become director of the Getty from 1983–2000.

At the time of his departure it was speculated that he had aspired to the position of director of the MFA which went to another curator Jan Fontein. Walsh departed under a cloud of controversy. As I reported for the daily Patriot Ledger documents from the Charity Desk of the Attorney General’s office revealed that Walsh earned about $25,000 annually as a consultant to the foundation of William I. Koch. While a salaried curator of the MFA Walsh advised Koch of acquisitions which initially went on display at the MFA as loans.

One of those former Koch works, Édouard Manet’s "Portrait of Madame Brunet" (1867), is now on view at the Getty. Was Walsh the middle man, first for Koch, and then the Getty? The Koch collection was later shown at the MFA in an exhibition brokered by now retired director Malcolm Rogers. The billionaire got to park his two America's Cup yachts on the roundabout in front of the museum's Huntington Avenue entrance.

During Walsh's tenure at the Getty the institution was mired in scandal.

In “Loot: The Battle Over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World,” by Sharon Waxmanm, she states that “One thing stood out about the Getty Museum, and that was the sex. Numerous current and former Getty employees describe the atmosphere from the 1970s onward as convivial in the most carnal sense of the word.

"'It was like Peyton Place,' was how one former employee described it. 'Sodom and Gomorrah' was the phrase used by another. Peggy Garrity, a lawyer who sued the Getty over a client’s sexual harassment claim, put it this way: 'They were fucking like rabbits behind the paintings.'"

When the Villa reopened in 2006 The Guardian reported that “Marion True, curator of antiquities for the Getty Trust and coordinator of the villa's programmes (sic), is on trial in Italy on charges that she conspired with antiquities dealer Robert Hecht to export illegally excavated treasures.

“True resigned in September following revelations that she had failed to tell the Getty that she had accepted a $400,000 loan from an antiquities dealer to help buy a house on a Greek island. But her presence dominates the villa…

“Several of the disputed antiquities are on show in the villa, most notably the huge marble and limestone "Cult Statue of a Goddess, Perhaps Aphrodite," dating from the 5th century BC.

“The case against True concerns 35 objects acquired between 1986 and the late 1990s. Her lawyers admit that some may have dubious provenance, but they deny she knowingly acquired items looted from archaeological sites.

“In October last year the Getty handed over to Italian authorities three items in its collection that were deemed to have been looted. More are expected to follow.”

To be fair scandals are not unique to the Getty. Perhaps because of its great wealth they appear to be more spectacular.

As we traveled on the tram to the museum above there was a sound track from current museum director James Cuno. We met him at the beginning of a spectacular career as director of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. Following the opening of the Charles Moore and Chad Floyd designed museum in 1985, for several years, I was a frequent guest in Hanover.

The centerpiece and cover of the catalogue of loans from alumni was a spectacular painting of “Mary Magdalene” by Titian. At the time I asked Hood curator, Hilliard Goldfarb, of the potential for the painting to become a Dartmouth acquisition.

Surprise. There it was at the Getty. To my eye it is a better example of Titian’s work than a scrubbed looking version, one of several, depicting “Venus and Adonis.” The original fragile, sublime and delicate glazes appear to be more intact for the smaller but exquisite “Mary Magdalene.”

The mandate of the Getty is to collect in the time line from ancient classical to 19th century. Even with the deepest pockets works worthy of the museum are hard to find. Which is why the curator Ms. True got caught with her hand in the cookie jar.

The Getty has crossed into the 20th century in the field of photography.

In 1964, Sam Wagstaff organized the landmark minimalism exhibition Black, White and Grey at the Wadsworth Atheneum. In 1973, he turned full time to collecting photographs. In 1984 he sold the photography collection to the J. Paul Getty Museum. He was the decade long partner and promoter of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

“I began to collect photographs with Patti Smith’s approval,” Wagstaff told a Spanish TV interviewer in the 1980s.

“He was buying things like a madman,” Mapplethorpe told Janet Kardon, director of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, in 1988. “He saw beauty on every level, from the amateur all the way up — in postcards and everything.”

Judith Keller, the Getty Museum’s senior curator of photography considered the Wagstaff collection the core of the museum’s holdings in photography. “It has the greatest range in terms of the history it covers.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Philadelphia Museum of Art were founded in the 1870s. The Art Institute of Chicago started earlier and modestly in 1866. The National Gallery of Art was established in 1937. Overall these museums have greater collections than the relatively new Getty.

During our tour of the permanent collection there were stunning highlights.

Consider “Irises” (1889) by van Gogh. The Museum purchased the painting in 1990. It had sold for $53.9 million in 1987. While among the most costly it is not one of his most iconic works.

Arguably, "Portrait of a Halberdier" by the Italian master Pomntormo (1528–1530) is a better picture and one of the finest works in the Getty. When the Museum bought the painting for $35.2 million at an auction in 1989, the price more than tripled the previous record for an Old Master painting.

We encountered two outstanding works by Rembrandt “An Old Man in Military Costume,” 1630 and “Abduction of Europa,” 1632. The small painting depicts Europa as a bourgeois Dutch lady being kidnapped by a randy bull. It is almost comic when compared to the Gardner Museum’s masterpiece which may be considered the finest Italian Renaissance painting in America. Fortunately, the thieves who looted the Gardner flunked Art History and overlooked the great Titian.

Considering the subject David’s “The Sisters Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte” (1821) is interesting but not particularly memorable.

There were some fine examples of Barbizon, Impressionism and Post Impressionism of which the most important is a veteran amputee making his way in Manet’s “The Rue Mosnier with Flags” (1878).

Within the limit of an afternoon we didn’t see everything. There was no time to explore the gardens designed by the artist Robert Irwin. Or the terraces, cafes and restaurants. For scholars the Getty houses one of the nation’s most renowned fine arts research centers and libraries. The East Coast equivalent is the Manton Research Center of the Clark Art Institute which is in the final phase of renovation.

With its staggering scale, dramatic hilltop vistas, and architectural glitz the Getty is very, well, LA. By which we mean more flash than substance. It may take a few generations until the collections live up to the Getty's well endowed potential.

During cycles of distressed economies great works come to market. It is anticipated that the Getty will be high bidder for the rarest masterpieces.