The Venice Biennale, 2007: Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Representing America: Part One

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 15, 2007

Felix Gonzalez-Torres: America

52nd International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale

Curated by Nancy Spector and the Guggenheim Museum

Catalogue with introductory essay by Nancy Spector and a conversation among Amanda Cruz, Suzanne Ghez, and Ann Goldstein who collaboratively proposed Gonzalez-Torres for the Venice Biennale in 1995.

The project was selected from proposals presented to the Federal Advisory Committee on International Exhibitions (FACIE) and the United States State Department's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA)

June 21 through November, 2007

The installation "Felix Gonzalez-Torres: America" in the American Pavilion in the Giardni della Biennale Venice, Italy, which is now in its final days having opened at the end of June, raises a range of issues and ideas many of which are difficult, complex and not easily resolved or understood.

The most glaring complexity is the lingering notion of Nationalism, an arguably superannuated holdover from the founding, in 1895, of the oldest of the now ubiquitous biennials. In an era of globalization and post colonialism as dominant concepts of current critical thinking it is significant to note that the artist representing the Unites States was born in Cuba. To proceed further he is the second deceased artist to represent his (adopted) nation, the first was Robert Smithson in 1982. The artist (1957-1996) died of AIDS and it is relevant to note this as it informs aspects of the work which are at the core of his art practice.

There is inevitably a lot of second guessing whenever an artist is given the level of recognition of being the American representative in the oldest and most prestigious of the now proliferating biennials said to number some 300 plus. Linda Norden, who presented Ed Ruscha at Venice in 2005 spoke with me of the many issues involved over Chinese dinner in Cambridge (Maverick Arts # 201) and we also heard her speak at MIT as a part of an international conference organized last Spring by Mary Sherman and her Transcultural Exchange. A report on the artist's talk at Harvard is covered in Maverick Arts #212. The Ruscha installation traveled in another form to the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Visiting the Venice Biennale recently there was the initial reaction while viewing the Gonzalez-Torres installation of yet another instance of déjà vu all over again. In many aspects the work if not minimal is at least slight. There isn't that much to see and we have had that opportunity on numerous prior occasions. For whatever reasons the artist was well established with major curators and the work appears to be so well vetted that one wonders if there is really anything new to say and feel about it. The artist conveyed his socially and politically charged message with such succinct conceptual clarity that it leaves little critical breathing room for doubt, debate, or any of the elements that sustain and breathe posthumous resonance into the now canonized work from a passed generation by a deceased artist. The only activity that now prevails is to throw awards at and pin medals on the now departed. It is rather like the work of Robert Mapplethorpe which became a household name only after his death through a circulating retrospective that rattled the chain of Congress and asshole politicians like the late Jesse Helms.

So tossing a bit of critical dirt and controversy on the shade of Gonzalez-Torres might serve the useful purpose of enriching and sustaining the reputation of the artist and his oeuvre. Enshrining it in the canon of contemporary art appears to be a mandate for Nancy Spector, the Chief Curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, who organized the artist's retrospective there in 1995.

That is surely a lot of curatorial and institutional muscle and a strong shoulder to the wheel driving the posthumous reputation of an artist. Representing the U.S. at Venice is the art world equivalent of earning a Gold Medal at the Olympics. But this is also problematic as National Pavilions are a troubling holdover of Imperialism and one might ask how the artist, were he living and given his subversive politically motivated work, might think about waving the flag for the U.S.A. Particularly during a moment when our government is in the midst of widely criticized wars resulting in the treatment of prisoners which appears flagrantly to violate standards of international law as well as our own Constitution.

But since the artist is not in a position to address those concerns, and the curator and museum are committed to presenting work about which they feel strongly, let us just give them a free pass while noting that the system is flawed. The Venice Biennale is the last and oldest such cultural project to adhere to discredited notions of nationalism. These are issues which Robert Storr, as director of this Biennale, addresses in his catalogue essay to which I refer you directly. In another essay I will discuss impressions of the other international pavilions of the Giardini as well as the major Storr installation there as well as the more free flowing installation of work assembled in the accompanying Arsenale. So stay tuned on that with more to follow.

Let us discuss the American Pavilion and its current exhibition. First one must consider the structure itself which looks rather 19th century academic, classical. Its Palladian plan and façade detail might have been designed by Thomas Jefferson or cribbed from the villas of Vicenza. Surely this must be a challenge for artists and curators to create contemporary installations for such a classical building. The distribution of space and its interior walls dictate a kind of perfect symmetry which artists have opted to emphasize or work against. In this case the objects and concepts of Gonzalez-Torres are so low key and understated that they occupy the container with seemingly not a whimper of resistance.

Part of the concept of the artist was that his hanging strings of light, arrangements of candy in wrappers, skids of posters, placement of photo murals and framed photographs, and other elements were left entirely to the discretion of the designated curator. The artist created/ selected elements which were approached in a modular manner. Accordingly, there is no argument about whether the curator/ installers have been true, or not, to his intention. This is not the case, for example, in the posthumous museum installations of works by Joseph Beuys few or any of which accurately convey his unique sensibility.

The artist evokes familiar issues and arguments of the avant-garde that were initiated by the found objects and readymades of Marcel Duchamp, mostly in the second decade of the 20th century, and in the seminal 1936 essay by Walter Benjamin "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." There is an ancillary debate about the notion of value in a work of art which Gonzelez-Torres accelerated masterfully and may comprise his most brilliant contribution.

As we approach the pavilion there are two, large, round, shallow, reflecting pools fabricated from Cararra marble. They each weigh eight to ten tons. They touch forming a figure eight. While the artist conceived and planned the work "Untitled" (Perfect Lovers) it was executed for this occasion and it is interesting to note that the artist never got to see it. But, again, because of its minimal form and conceptual nature in no way does it misrepresent the intention of the artist. This was not the case when Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo of Varese, Italy attempted to fabricate a series of plywood sculptures according to plans he had purchased from Donald Judd. Even the most simple and obvious of plans may prove to be not so. But here Spector has proceeded with apparent impunity. Of this new work Spector has been quoted as saying that "They're beautiful and I think people will probably throw coins in them, or might actually get into them if it's hot. I wouldn't mind." How cute.

In the entrance hall is suspended a lightbulb string with twelve illuminated strands. It is the only lighting in the room and ends in a coil on the floor around an embedded circular design pattern. There is another of these light strand pieces providing the only illumination in a room to the right which has one large photo mural of a seemingly empty, black and white image of sky with a single flying bird.

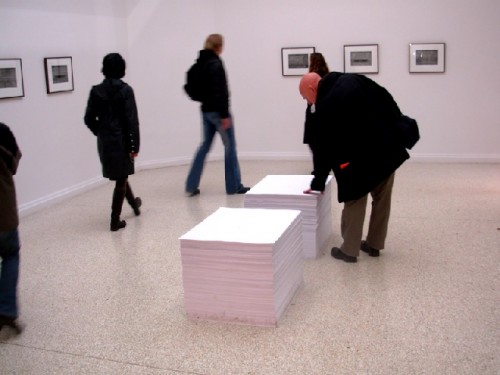

One room/ gallery is surrounded by a series of framed, generic, photographs of texts from the monument to Theodore Roosevelt on the exterior façade of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The single, framed words convey the attributes of the former American President: Author, Statesman, Scholar, Humanitarian, Historian, Ranchman, Conservationist, Explorer, Naturalist, Scientist and Soldier. These images surround two paper stacks (originated in 1989 but printed and replenished since then) "Untitled" (Monument). The paper posters which visitors are invited to roll up and take away bear the texts "Memorial Day Weekend" and "Veterans Day Sale." The artist in this manner comments on the commercialization of holidays intended to honor losses and service to the nation. He was either trivializing or making an important critical comment on the notions of loss and sacrifice. This concern appears to be lost on visitors who jump in and grab a poster. As is the case with two other stacks of "free" posters in another gallery including "Untitled" (Republican Years), 1992, a large white sheet with a "funereal" black border, and a dark, black and white detail of an ocean surface "Untitled" 1991.

The final gallery on the left displays a carpet of cellophane wrapped, hard, black, licorice candy "Untitled" (Public Opinion) 1991. This work is accompanied by what the press release describes as a selection of "Â…early photostats- blank, captioned screens that cite political and social events in eccentric inventories of the collective consciousness." Again, visitors were allowed to take the candies but this appeared to be occurring more sporadically than the enthusiasm for acquiring posters.