Art of the Americas at the MFA

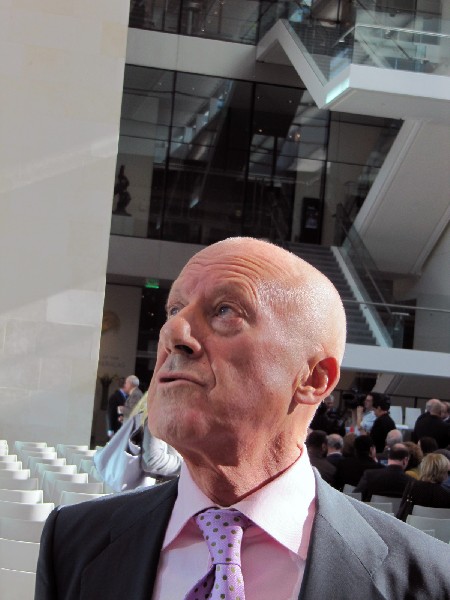

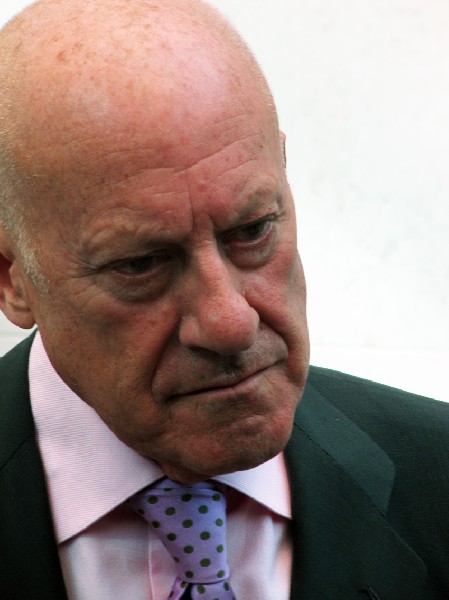

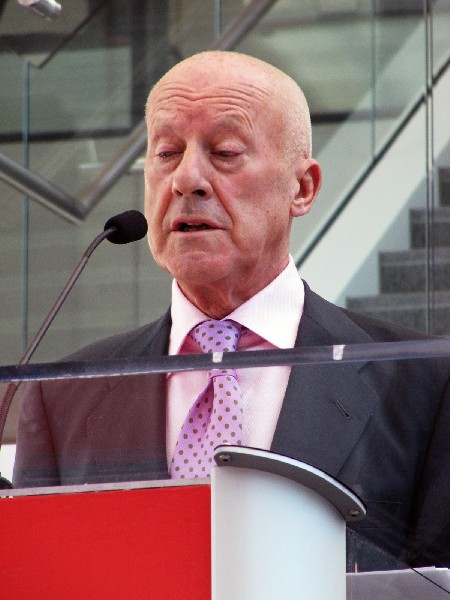

Lord Norman Foster Partners with Malcolm Rogers

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 16, 2010

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Paul Revere’s Ride

The British are coming.

By land, British born, now American citizen, Museum of Fine Arts director, Malcolm Rogers. By sea, well, air actually, architect, Lord Norman Foster.

Through a project that has taken ten years they have put a British spin on creating the Art of the Americas wing for the MFA. Before construction the MFA was a complex of buildings comprising 483,447 square feet. Of that 59,835 square feet were demolished. With 193,325 square feet of new construction that means a 28% increase to 619,937 square feet. There are 53 galleries in the 121,307 square feet of the new wing. With 51, 338 square feet of exhibition space that is an increase of 42% for displaying the Art of the Americas.

Currently there are 5,000 works of the Americas on view which is double what was previously displayed. During a time of an economic downturn Rogers oversaw a $504 million campaign for construction, acquisitions, endowment, and programming. In the new wing, unveiled this week with a series of galas and events, there are 500 new acquisitions and 175 works on loan.

With this extreme makeover, the most extensive and ambitious of any cultural organization in the history of New England, now in his 16th year at the museum, Malcolm Rogers has put an indelible stamp on the institution.

In remarks during the dedication ceremonies Rogers discussed an enormous portrait by John Singleton Copley of the Prince of Wales. The son of King George III supported the Colonies during the American Revolution. Copley was Boston born but departed for England just before the war of independence.

Rogers compared himself to Copley and the Prince of Wales, as British born, but now an American citizen. “The painting was rolled up and in storage” he said. “It has been beautifully restored and is now one of our largest American paintings on view.”

The scale of the Foster designed wing has allowed for enormous works, that have languished in storage, to be put back on view. During the press conference Rogers was asked where the MFA had found the epic scaled “King Lear” by the 18th century, Philadelphia born, British school painter, Benjamin West. Warming to the tale he informed the media that it was one of the most famous paintings of its day. “You can find reproductions of it in antique shops” he said. During some 50 years of visits to the MFA I have seen it from time to time but now it regularly will be displayed.

When he took over Rogers inherited a museum with great collections that had fallen on hard times. He faced a tight budget that called for immediate staff reductions that included the summary dismissal of department chairs and senior curators. It got ugly. He broke up the traditional fiefdoms under the mantra of One Museum. In more common language it was “My way or the highway.”

Even though Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., the John Moors Cabot Curator of American Art, was offered the position of Chair of the Art of the Americas, he departed for the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University.

Initially, nobody was sure just what Rogers meant by consolidating independent departments under one umbrella. In 2001, Elliot Bostwick Davis joined the MFA as John Moors Cabot Chair of the Art of the Americas. She came to the museum from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Davis comes from a family of distinguished collectors including Louisine Waldron Havemeyer, and Electra Havemeyer Webb.

As Chair of the department she presides over a collection of 15,000 works and a staff of ten curators with a range of specialties. In Rogers’s vision of the Art of the Americas that means telling the entire story of 3,000 years and two continents. It is now displayed in a free standing structure on three floors, with a lower level of galleries, designed to be nested within the original Guy Lowell, Beaux Arts building of the early 20th century.

When I.M. Pei designed the West Wing he attempted to make sense of a warren of galleries. By reorienting the entrance to the museum the intent was to create two loops. A visitor might follow a circular route that led through all of the collections on two levels. The grand entrances were down played and for a long time the Fenway entrance was closed. The magnificent stairs from the Huntington Avenue entrance no longer led to the special exhibition galleries which were transformed into the library.

With the Gund special exhibition gallery, Foster Gallery for contemporary art, restaurant, café, book store and lower level cafeteria, the majority of visitors never ventured far from the West Wing.

After intensive study with the curators the Foster team decided to restore the original intention of the Guy Lowell design. Toward that end the West Wing entrance is now closed other than to bus loads of school children and tours.

The insertion of the new Foster designed, free standing structure, has been executed with surgical precision. From Huntington Avenue there is no disruption of the Lowell façade. The brilliant design decision has been to create a museum within the museum. It is the kind of solution which Foster + Partners have become known for particularly in the use of glass to achieve transparency and light.

The firm is now one of the largest in the world known for The Great Court of the British Museum, German Parliament in the Reichstag, Berlin, Hearst Headquarters in New York and the Winspear Opera House in Dallas. Currently they are involved in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. It has an enormous collection on a campus of long neglected buildings.

While truly spectacular, and staggering in its ambition, a first impression of the collections in the new wing quickly reveals their greatest strengths and most glaring gaps. By assuming to be encyclopedic it is now mandated to pay attention to dozens of tributaries and sidebars.

It’s a daunting challenge to create a cohesive visual narrative. While many museums excel at aspects of the story of the Art of the Americas no other museum has aspired to cover the entire history from broad swaths, like Copley, Colonial portraits, decorative arts, and furniture, to vignettes as minute as a single work. For example, there is currently just one painting by Hyman Bloom on view. It signifies the major chapter of Boston Expressionism which prevailed during the Depression years of the 1930s through the post war era of the 1950s.

Today, Malcolm Rogers rightly deserves to be regarded at the museum’s greatest single director. During my lifetime of covering the MFA, starting with Perry T. Rathbone, no individual can match his accomplishment. Bravo. But that is said with the caveat that he has a dark side. Rogers has been pilloried as a vulgarian who has embraced kitsch and mediocrity.

Others would describe him as a populist who made the museum more inviting. Experts, critics, and art historians observe that he has accomplished that by showing cars, guitars, cartoons, and celebrity photography by Herb Ritts and Yousuf Karsh. Sucking up to billionaire William I. Koch, the “collector” with more cash than taste, he got to park his America’s Cup yachts on the front lawn. As well as show off his empty wine bottles and Indian war bonnets. In the kind of wooing that entails Koch has loaned key works to the museum's new wing.

To be sure Rogers pulled no rabbits out of the hat any more outrageously than the now ousted, Tom Krens, formerly the director of the Guggenheim Museums. Under his watch, the New York museum turned its spiral over to motorcycles and a tribute to the fashions of Armani. Actually, it loved the Armani show which was brilliantly installed by Robert Wilson. Those exhibitions boosted attendance but were trashed by the art press.

Bathed in a wash of brilliant sunlight, on a gorgeous autumn day, we gathered in the Ruth and Carl J. Shapiro Family Courtyard for a program in dedication of the new wing. Breakfast was served to the assembled VIPs and media. It was an exciting opportunity to chat with so many who have followed the museum for decades.

We spoke with collector of prints and drawings Lois Torf. She recalled a Board of Directors meeting when then director, Alan Shestack, announced that as a budget cut they were closing the Fenway entrance. Staffing it cost some $80,000 a year. It was more than the museum could afford at the time.

Friend and adversary Clementine Brown, formerly the director of public relations and marketing under Jan Fontein, recalled our scraps back in the day. There is a gallery in the new wing named for her. Although we often went toe to toe on breaking news there was the exhilaration of fair fights. Until the time I was working on a scoop and she dimed me to the Globe. Today we can laugh about it.

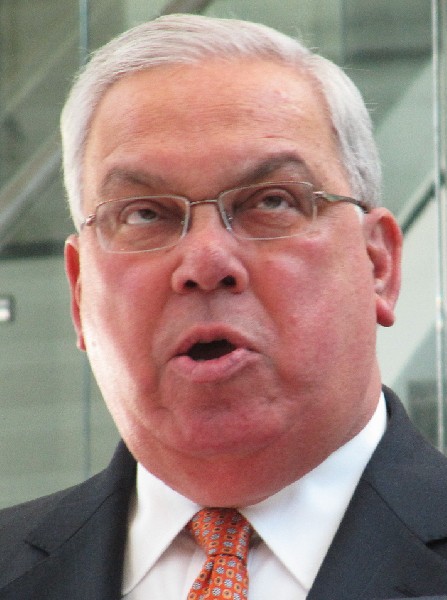

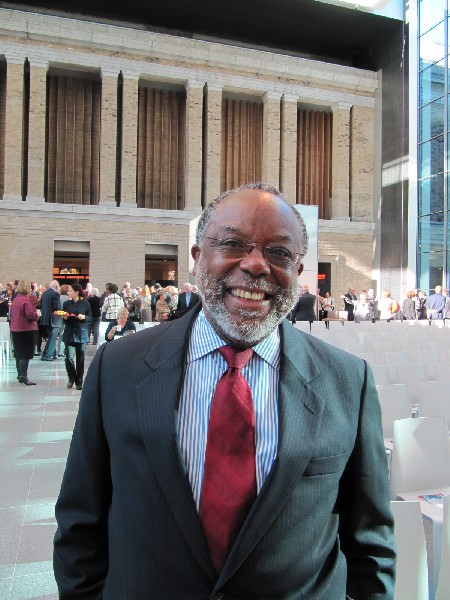

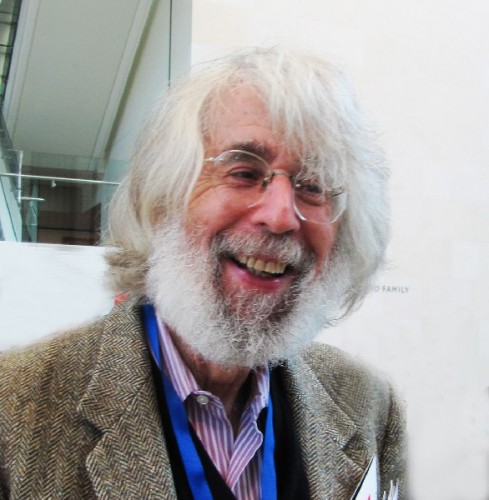

Berkshire Fine Arts critic, Mark Favermann, and I, were surprised when Malcolm joined us for a chin wag. While Mark snapped a picture I gave Malcolm a hug for old time’s sake. I said to him “How about a kiss.” Never missing a beat, the ever suave and witty Rogers responded “That costs more.”

There were lots of other critics hovering about. It was great to speak with Lloyd Schwartz of the Phoenix one of our most distinguished writers on classical music. Greg Cook the art critic of the Phoenix was taking quotes from Davis.

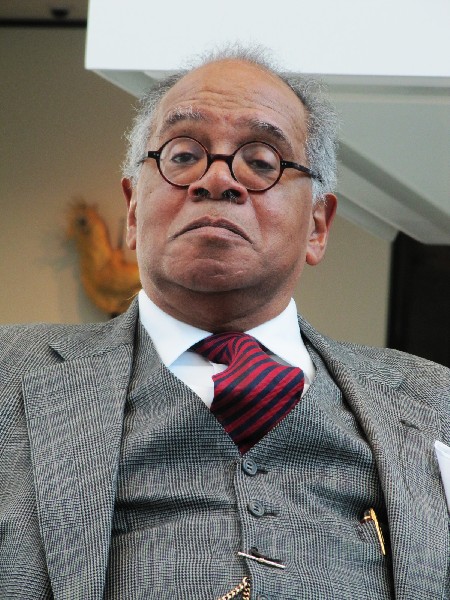

It talked with Florence Ladd the former director of the Bunting Institute of Harvard. Similarly, we caught up with Ted Landsmark the director of the Boston Architectural College. I taught for BAC during my final year in Boston before moving to the Berkshires. Ted filled me in on the expansion into the former ICA building on Boylston Street.

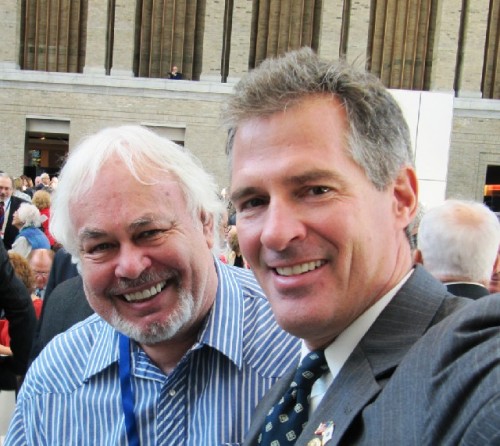

There were lots of diplomats and dignitaries floating about. We spotted Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley. It was my first encounter with Senator Scott Brown. Snapping away he said “Charles, you’re freaking me out taking all those pictures.” Grabbing my camera, he held out an arm, and took a shot of the two of us. I rarely consent to be being photographed with Republicans. We also managed to get up close to Lord Foster who was touring the space with dignitaries.

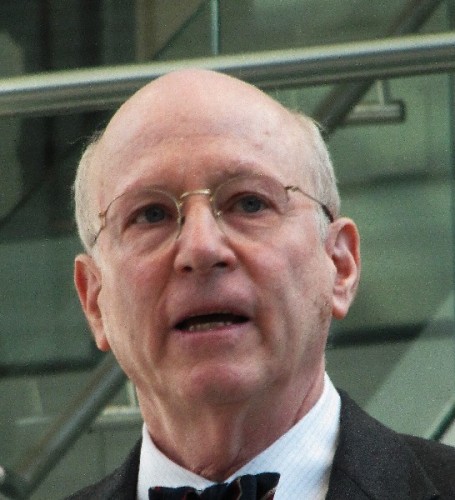

We settled in for the dedication. The opening remarks were made by Richard Lubin, Chairman, The Board of Trustees. He was followed by Rogers and Lord Foster. Senator Brown spoke of coming from a family of artists and how overwhelming he found the experience of the new wing. Conspicuously, Governor Deval Patrick was absent from the podium.

Michael E. Capuano, Representative of the 8th Congressional District of Massachusetts, spoke of coming from a family of immigrant shoemakers. Growing up in East Boston, when passing by the MFA, he recalled not feeling welcome. He contrasted that with how Rogers has opened up the museum to all. Particularly, the once closed entrance to the now improved Fenway.

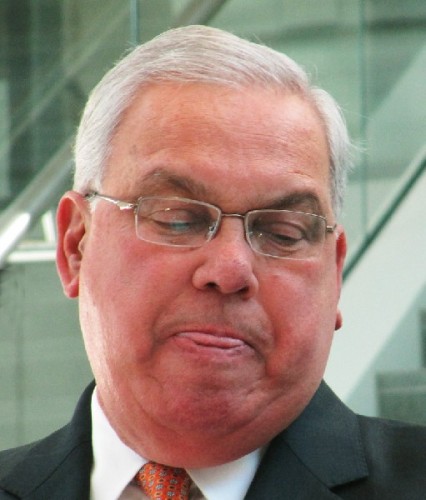

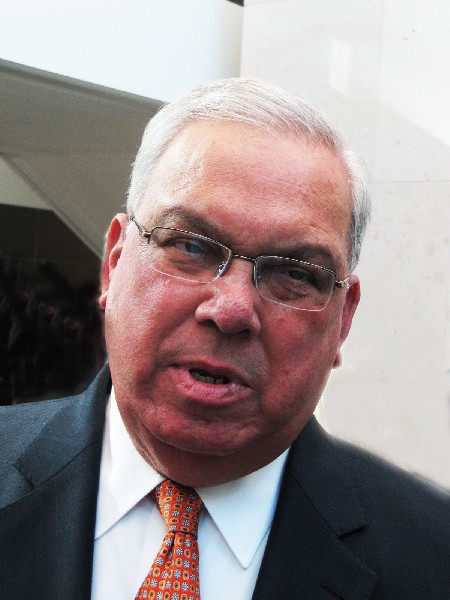

There was a fanfare when The Honorable Thomas M. Menino, Mayor of the City of Boston, mounted the podium. He took a bow evoking a laugh from the audience. He told us that he assumed the fanfare was for him. Then he chided Capuano for “stealing my speech.” What followed was mostly incomprehensible.

Barbara L. Alfond, President, the Board of Trustees, informed us of how honored she felt that these great changes fell to her watch and that of Lubin. They were successful in soliciting donations from so many individuals. Reverend Peter J. Gomes of Harvard offered a benediction.

Rogers noted the incredible economic impact of the museum. It is anticipated that the attendance of the MFA will spike in the coming year. That represents an economic boom to the city. The museum is one of the largest employers in Boston.

There is more to be done. In September, 2011 the museum will reopen the Linde Family Wing for contemporary art. It will occupy space renovated in the former West Wing designed in 1981 by I.M. Pei. In the former Gund Gallery there will be seven named galleries for aspects of the growing permanent collection from 1970 to the present.

This is an area of notorious weakness for the museum with a track record of mediocre accomplishments under Rogers and former curator Cheryl Brutvan. We anticipate surprises, however, between now and the reopening a year from now. Boston is not noted for collectors of contemporary art. There are a few. But the demise of the Rose Art Museum, at Brandeis University, a scandal and tragedy, has reconfigured the landscape. Former Friends of the Rose are now looking elsewhere to gift their collections.

While we anticipate progress in the vital area of modern and contemporary art there is guarded optimism. It is noteworthy that Rogers said that “We do not want to be an ICA.” Since the ICA has had its own historic struggles, and is just beginning to form a permanent collection with little space to display, or store it, that is not encouraging news. Consider that the contemporary wing of the MFA, when completed, will be larger than the entire exhibition space of the ICA.

Among visitors touring the museum, during the opening festivities, there was a sense of euphoria. Surely this is an incredible accomplishment. There wasn’t enough time for us adequately to absorb 53 galleries. But already they seem cramped. Where is the room for growth and expansion in decades to come? We are assured that the galleries will be rehung in cycles. As the museum addresses the gaps of the Art of the Americas just where will they put new acquisitions? Collectors are not eager to donate works that will go into storage.

The museum has empty space in the footprint of its campus. There is a now redundant entrance to the West Wing including a drive around and outdoor parking lot. How soon will the museum need to expand yet again? Not on Rogers’ watch. He is now 62 and his great work has been accomplished. We anticipate his retirement within the next five years. Surely he will leave the MFA in better shape than he found it.

For now the MFA has succeeded in catching up. But there is an ancient rivalry with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is the art world equivalent of the Red Sox and the Yankees. The current MFA is bigger than Madrid’s Prado Museum, and slightly smaller than the Louvre, believe it or not. But its 616, 937 square feet compares to the Met’s 2,200,000 square feet.

Curators and experts will assure you that, object for object, the MFA is among the elite of the world’s great museums; particularly in the Art of the Americas. Much has been accomplished but there are miles to go before we sleep.

Link to Boston Phoenix article by Greg Cook