Cape Ann Museum Taken for Granite

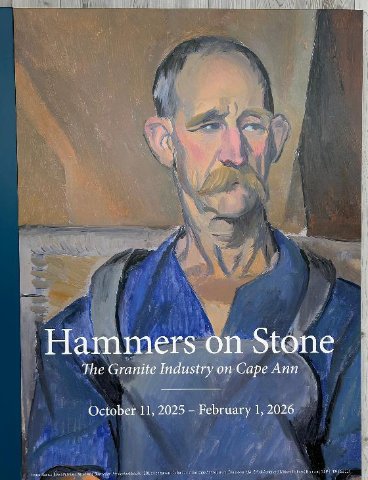

Hammers on Stone: The Granite Industry & Cape Ann

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 16, 2025

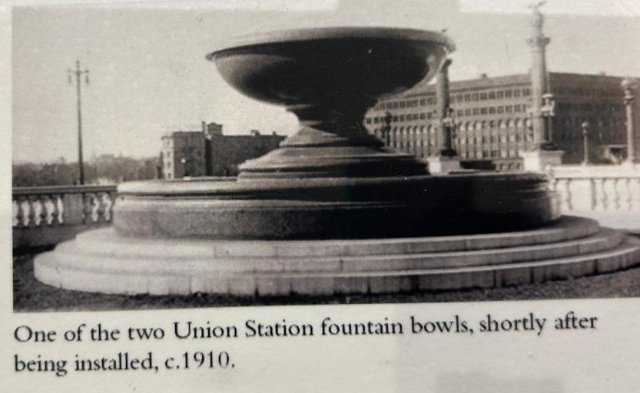

Cape Ann/ Gloucester is rightly know for fishing. A second industry that sustained for a century entailed quarrying for granite. It was a building and decorative material that was shipped all over America as well as internationally.

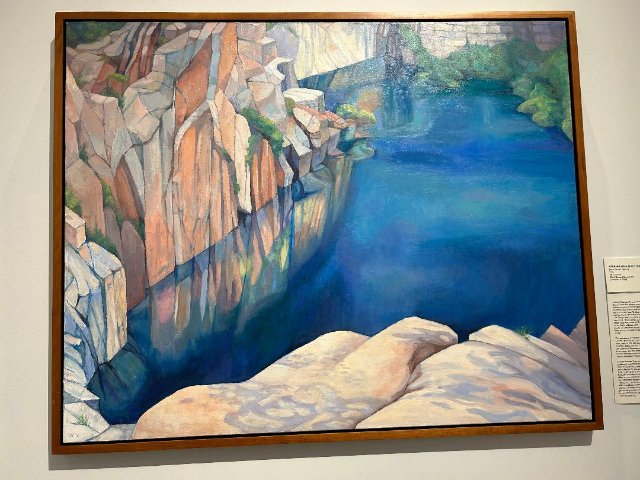

There are water filled abandoned quarries all over but primarily from Annisquam and Lane’s Cove to Rockport. Many are on private land but some are accessible to swimming.

The 18th century saw the start of stone cutting on Cape Ann. It became a commercial industry in the 1820s. By 1892, some 900 men worked at quarrying and related jobs. Up until the 1930s there were more than four dozen working quarries. Not all were large. A site requiring just one or two workers was called a “motion.”

Near the quarries resided the Finns and Italians who cut and dressed the stone. My Irish great grandfather and his brothers started from Canada and worked their way down from quarries until they settled on Cape Ann. They were a part of the crew that cut stone for Rockport’s massive breakwater.

The Cape Ann Museum is under reconstruction with a launch planned for late June. Until then there are exhibitions at its annex on the Cape Ann Museum Green which is just off the Grant Circle rotary at the end of Route 128. There is ample parking and free admission.

The current exhibition Hammers on Stone: The Granite Industry & Cape Ann on view through February 1 is a gem. Given the nature of the show it may be described as a diamond in the rough. It has been superbly curated and installed by Martha Oaks and Leon Doucette.

Initially I was skeptical. After all, just how engaging might be an exhibition about granite? It would seem that there are more exciting ways to get stoned.

Call me Rocky but I was enthralled by this compact and insightful show. It has been tastefully installed with a heady mix of artifacts and works of art that spell out this chapter of Cape Ann history with depth, panache and nuance.

Including wall signage and informative labels there was much to learn and absorb. It was a show to linger over as we did for the better half of an afternoon. If you can this is a show that you might want to visit several times and be sure to bring friends.

There is a judicious balance between tools and ephemera of the industry as well as a superb and insightful mix of works from the museum’s collection that further enhance and illustrate this history. Most intriguing was the manner in which granite and the quarries inspired artists.

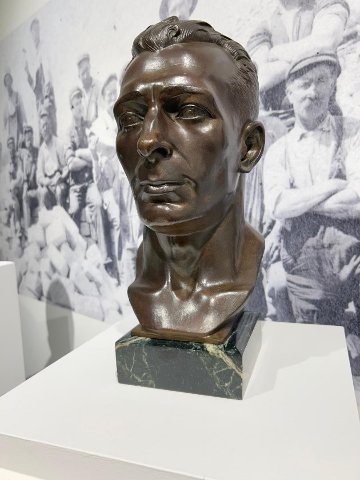

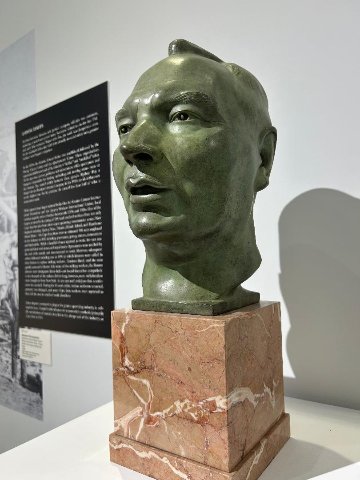

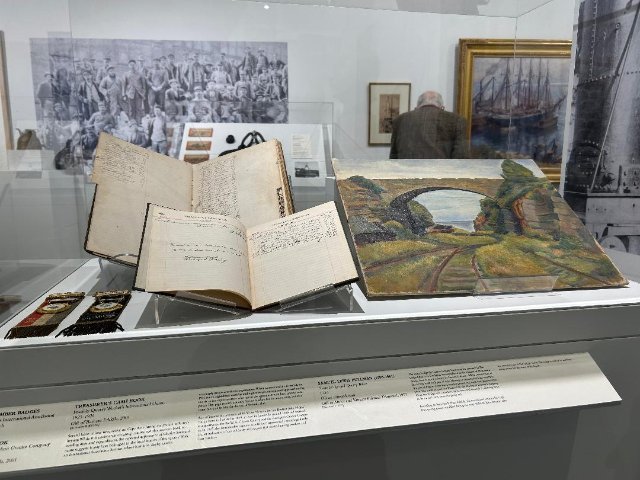

That is conveyed in a mix of bronze busts by such eminent sculptors as Walker Hancock and George Demetrios. Hancock depicts young boys while Demetrios had an eye for his ethnic neighbors who worked the quarries. There were representational landscapes and portraits as well as prints. There are intervals of engaging with photo murals of the ruddy workers and the now rusty tools of their abandoned trade. In vitrines we see such vintage items as union badges and account books.

Once taken from the quarry there are works that focus on shaping the material into paving stones which were used all over America. We encounter a model of a sloop as well as a singular bravura painting of a five-masted schooner by the master Emile Gruppe.

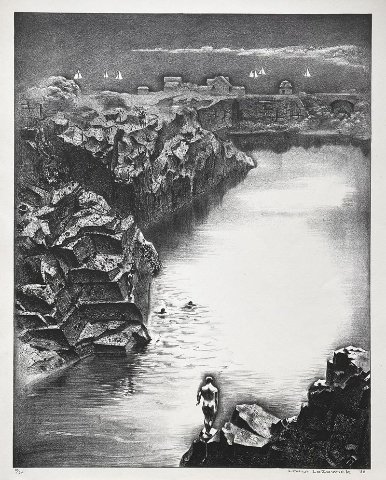

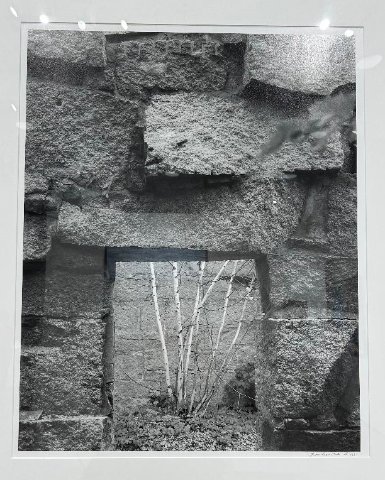

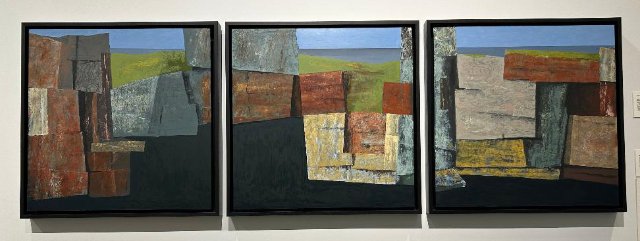

Several fascinating works entailed modernist and minimalist responses to stone and quarries. An abstracted painting by Barbara Swan was fairly literal. Works by Michael McKinnell, David Crowley, Lawrence Fane and photographer Steve Rosenthal were not.

It was surprising to learn that the abstracted, block-like, geometric triptych by McKinnell was created by the renowned architect of the brutalist Boston City Hall. It is a less then beloved monument created by Kalmann, McKinnell and Knowles. In so doing they destroyed historic Scollay Square. Here we see him as an artist.

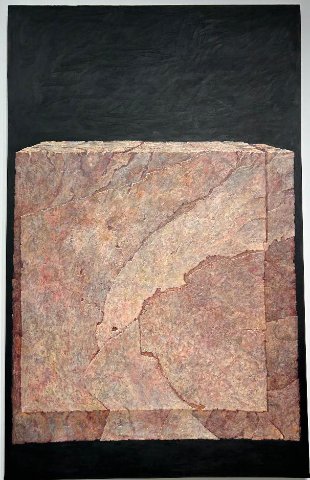

The large, minimalist, block of granite “Cathexis” (1983) created in a trompe l’oeil manner by Crowley takes this exhibition to another level. This is work that I crave to see more of.

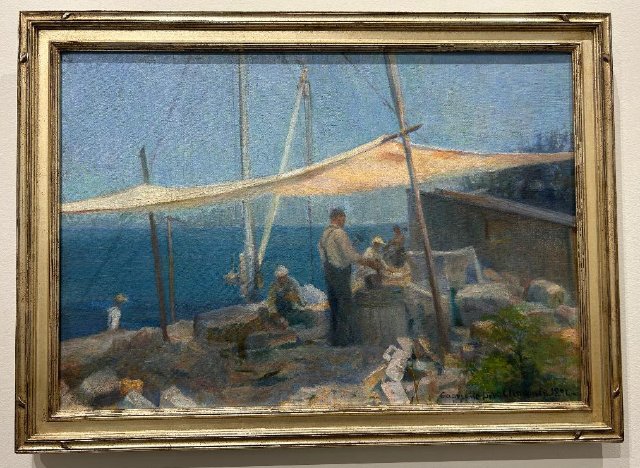

The more representational paintings augment the theme of the show. Gabrielle de Veaux Clements is a renowned Gloucester artist. She is represented here by “Motion at Folly Cove” a painting from 1894. It depicts workers making cobble stones under a protective canopy in the heat of summer. There is also a print on that subject.

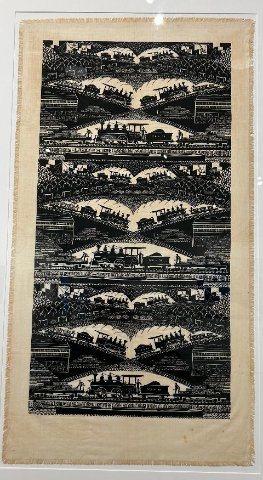

Eino A. Natti was a founder of Folly Cove Designers, he is represented by “Table Runner with Polyphemus” (1950). It is a narrow, vertical design created by linoleum block print on linen. The original intent was pragmatic though now it is framed as a work of art. Eino Natti was born in Gloucester to Finnish immigrants Erik and Matilda Natti. He graduated from the Boston Museum School and attended Northeastern University. Natti's sister Anna Stephanio and his sister-in-law Lee Kingman Natti were also Folly Cove Designers.

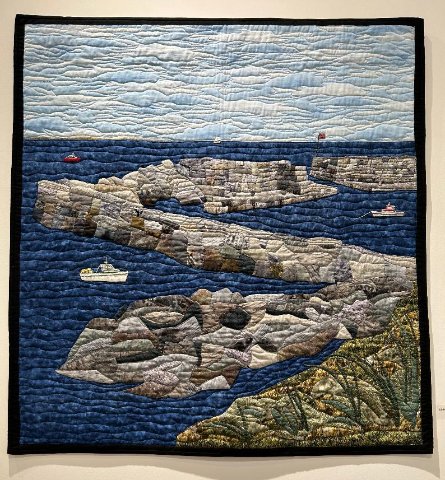

Some works prove fixating for their difference. There is a wonderful fabric piece by Dorothy Elizabeth Prouty who was a renowned Gloucester teacher. The familiar “Lane’s Cove” is lovingly captured in a 2017 work entailing appliqué, embroidery and cotton cloth. With charming nuance she captures the varying textures and colors of sky, water and that formidable granite structure that protects the intimate harbor. It’s one of my favorite sites to visit on Cape Ann.

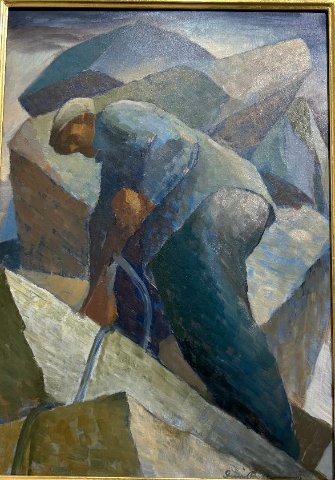

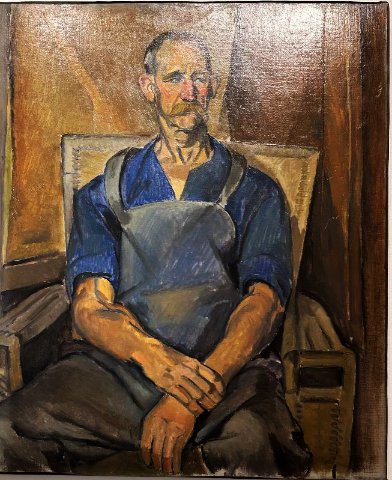

Let’s conclude with the poster image by Samuel Lewis Pullman (1900-1961), “Quarryman Joe Boston,” 1930. It was created not long before his passing. It conveys survival of a difficult profession. Ingesting granite dust was an occupational hazard. He gazes out at us with resilience and deeply expressed character.

That’s emblematic of Gloucester folks who toiled the sea and blasted into an island of stone. Let’s honor the sanctity of their labor.