Sir John Eliot Gardiner's Beethoven Ninth

Revolutionnaire et Romantique Triumphs at Carnegie Hall

By: Susan Hall - Nov 17, 2012

Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique

The Monteverdi Choir

Sir John Eliot Gardiner, Artistic Director and Conductor

Elisabeth Meister, Soprano

Jennifer Johnston, Mezzo-Soprano

Michael Spyres, Tenor

Matthew Rose, Bass

BEETHOVEN Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9

Carnegie Hall

November 16, 2012

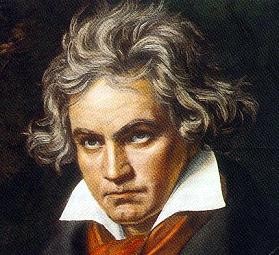

Sir John Eliot Gardiner brought Beethoven to Carnegie Hall. He chose Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage based on a Goethe poem to open the program. It was the calm before the storm, a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth, his most ambitious and longest work.

The Ninth has transcended the stratosphere in its almost two centuries of performance. But not in Gardiner’s hands, where it is clearly at ear and heart level. His orchestra of superb musicians, playing on period instruments, follows Beethoven to a tee. The infinite details, as they build step by step during each movement, were made patently clear, and then magnified by Carnegie Hall’s superb acoustics.

Instead of intimidating, its complexity shone forth with a particular clarity in the orchestra, one of the great choirs of the world and four superb soloists. Four hundred musicians have sometimes been deployed to perform, but the music rings out and stirs the soul even more from this modest number, which does not the flood the audience. At times intimately conversational, the musicians seem to talk like chamber music performers.

The Ninth has been compared to the greatest of all human achievements: the pyramids, Machu Pichu, and Angkor Wat. None of the myriad of appropriations by popular media, "A Clockwork Orange" among them, has diminished Beethoven's testament to man’s freedom.

The first movement was unusually restrained. Although the music is sometimes combative, the texture remained transparent. Four horns add nobility to the proceedings. Toward the end of this movement, the horns are heard in the distance as the oboes come forward, with accumulating energy. Seated on a raised platform with the singers, they soared.

The second movement, combining a scherzo with a five voice fugue, is puckish at the start. Beethoven dictates a regular beat, but Gardiner brought forward the beats which begin to switch every three or four bars. Shifts in accentuation especially on downbeats startle, as familiar as they may be. The work outgrows its beginnings.

The Adagio, often excrutiatingly slow, engages our attention with its vivacity and underlying intensity. The timeless pace was not a challenge for Gardiner as he drew forth beautiful, langorous phrases. Compared to a recent, 'stretched' performance of the Ninth which lasted 24 hours, Gardiner was in fact in a rush.

Both ardent and tender themes are handed off from violins and violas back to the woodwinds with the oboes then taking the lead. The violins pick up again, accompanied by the woodwinds. An unexpected salvo from the horns and trumpets interrupts. All the instruments come together for a peaceful conclusion. Gardiner moves easily from blaring horns to pastoral quiet.

The fourth movement is the longest Beethoven ever wrote, a symphony within a symphony. Trumpets, horns, woodwinds and timpani announce their arrival. The cellos begin a theme that will become the famiiar celebration of joy. It hardly gets underway before we hear the recapitulation of the themes of each of the preceding movements. This looking back is presented in a tantalizing evocation, reflective and yet eagerly pressing forward.

Early themes are rejected in favor of the theme of joy. The cellos and violas introduce the tune, but the bassoons soon join in counterpoint. Positioned on a slightly raised platform, musicians danced as they played. The horns and trumpets join to set the orchestra ablaze. Suddenly cymbals, triangle, piccolo and bass drum signal a marching band.

The soloists were splendid. Michael Spyres, an up and coming American tenor, stood out.

The conclusion is thrilling, the instrumentalists and chorus blanketed in a mystical aura, in which music erupts suddenly and violently but also consoles.

When Bernstein performed the Symphony at the dismantled Berlin Wall in 1989, he famously replaced the word Joy with the word Freedom. The ultimate symphony became the symbol of large extramusical themes: humanity, power, faith, human potential. But its dimensions were human. Although the Carnegie audience was wildly enthusiastic, a military squadron did not have to be mustered in New York as it was at the symphony's premier.

George Bernard Shaw remarked that some people came to hear Beethoven to be elevated. Even if the musical accumulation has that effect, the sheer magnificence of the music dominates. The Orchestra Revolutionaire and Romantique wove both of its titled missions tight together for a wonderful performance of the Ninth, fresh as ever.