Art of the Americas

Agony and Ecstasy of 3000 Years

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 18, 2010

Evaluating the world’s great museums entails more than comparing the square footage of galleries or the number of objects in a collection. If statistics were the only criteria then the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with its vast scale and encyclopedic collections, would be hands down beyond comparison to Boston’s considerably smaller Museum of Fine Arts.

In certain areas the MFA is second to none. Its holdings of Old Kingdom Egyptian Art are second only to the Cairo Museum. The Asiatic collection has no peers. As the MFA affirms with its new Art of the Americas wing it is a force to be contended with. By stating that it has on display examples of works from two continents, spanning 3,000 years to 1970, there is chutzpah and enticing charisma in that branding. By comparison, the Met houses its extensive and comprehensive collection in its American Wing. That just doesn’t seem to have the same ring.

So is this a marketing strategy of unabashed overstatement? Surely it puts the museum on a higher level as a cultural and tourism destination. Now, more than ever, no visit to Boston will be complete without a visit to the Museum of Fine Arts. Arguably, that has always been true. Now, more so.

Hyperbole, however, always invites scrutiny. Is Miss America really that beautiful or talented? Was that Oscar winning Best Picture really that interesting? Think about “Dances with Wolves” or “Oliver” for example.

So the MFA is begging the question as to whether it does, indeed, have the greatest single collection of The Art of the Americas. The knee jerk answer, based on a tour of the new, free standing building designed by Foster + Partners, with 53 galleries on four floors, is well, yes and no.

It depends on what you expect or are looking for.

There are areas of formidable depth as well as swaths of that history with just token representation. In order to fill the gaps, as a part of the ten year, $504 million campaign, the curators have made 500 acquisitions and secured some 175 loans. The very fact of such an ambitious undertaking, and dazzling new structure, creates a critical mass that will generate energy and attract gifts from major collectors.

If, that is, the major works sought by curators are there to be had.

In forming great museum collections luck, serendipity, and windows of opportunity are crucial. As well as, the interest and commitment of the institution, its trustees, and the community they serve. There are moments, or golden ages, when all of these forces converge. They result in great collections.

When Egypt, for example, granted permits to four teams to excavate around the Pyramids of Gizeh they drew lots. George Andrew Reisner, of the Harvard/ MFA crew was designated the area around the smallest of the three Pyramids. But it yielded the greatest treasures to be divided with the host nation. The MFA secured the stunning sculpture of “King Mycerinus and His Queen.” With a bit of Yankee horse trading, Reisner managed to hold on to the “Bust of Prince Ankh Haf,” arguably, the finest single example of Old Kingdom sculpture. It is one of the MFA’s greatest treasures.

Similarly, during the 19th century, three men were together in Japan. Over a period of time Ernest E. Fenollosa, Edward S. Morse, and William Sturgis Bigelow acquired and left to the MFA a collection that includes several Japanese National Treasures.

On the advice of William Morris Hunt, Bostonians in France, returned with a trove of Barbizon paintings. They also developed a passion for Impressionism. It resulted in great depth. During the Depression years of the 1930s the museum acquired the masterpiece of Paul Gauguin “D'où Venons Nous / Que Sommes Nous / Où Allons Nous.”

Mrs. Jack Gardner, with the art historian, Bernard Berenson, acquired many masterpieces including, arguably, the greatest Italian Renaissance painting in America, Titian’s “Abduction of Europa.” One would expect that her collection would be left to the MFA.

The strong willed and independent Mrs. Jack had other ideas. She moved from the Back Bay to create her own Palace on the Fenway. As a New Yorker she felt snubbed by Boston society. Creating her own museum was a nice way of getting even. When she “borrowed” Sargent’s enormous “El Jaleo” from a friend she quickly built it into its own gallery. So convincingly that she never gave it back.

The history of great collections are full of tales of triumphs as well as the “ones that got away.”

The influence of Ananda Coomaraswamy extended beyond his position as curator of Asiatic art at the MFA. His opinion prevailed over a broad sweep of aesthetic issues for the museum. He was opposed to collecting what was then contemporary art. When Georgia O’Keeffe, a friend, gave him a remarkable trove of prints by her late husband, Alfred Stieglitz, he stuck them in a draw. They were, at the time, just photographs. Later they were tracked down. Like many museums, the MFA was initially diffident about photography as a legitimate art form. In the new Art of the Americas it is given its own gallery. Perhaps, one day, it will deserve its own wing. Bundled with film, video and digital arts.

Although Bostonians were quick to embrace French Impressionism, by the Depression and Post War years, they abandoned modernism. There were no great Picasso’s in the mansions of the Back Bay, Prides Crossing, Eastern Point, South Brookline, and Marblehead. The MFA later paid dearly for a few examples including none of his masterpieces. The museum still lacks a great Matisse or a single work by Mondrian or the more rare Malevich. Bostonians ignored Abstract Expressionism and turned their noses up at Pop Art. Former curator Trevor Fairbrother managed to acquire a Warhol “Electric Chair.” But the MFA is just getting started in Pop, Minimalism, and post 1970s acquisitions.

Significantly, that was the great strength of the Rose Art Museum. The fate of which is now tragically unclear. But the demise of the Rose may be a boon to the ambitions of the revitalized MFA.

Aesthetic snobbery comes with a terrible cost. When trustees finally heed the advice of curators the cost of contemporary art is by then through the roof.

The MFA only created a department of contemporary art in 1971. They didn’t even consider the art of our time until the 20th century had all but slipped away.

The curator, Kenworth Moffett, managed to talk the collector Alfonso Ossorio (1916-1990) into parting with the Jackson Pollock masterpiece “Lavender Mist.” The asking price was about or under $1 million. When it was on display in the Trustees Room questions were raised about its future conservation. The chief conservator, William Young, didn’t have quick or easy answers. The MFA passed on the painting which quickly was acquired by the National Gallery.

Unquestionably, this masterpiece by Pollock would have been a focal point around which to build a great collection. Later, having learned its lesson, the MFA paid dearly for Pollock’s “Troubled Queen” an important but lesser work from a transitional period. To acquire the Pollock the museum traded apples for oranges. It deaccessioned two Renoirs and a Monet and added cash to acquire the Pollock. Currently, it is on view in the Art of the Americas wing. The museum also owns a more representative drip style painting by Pollock “Number 10.” It was a consolation acquisition for Moffett who has always maintained that it is a first class painting.

In the Boston Globe Sebastian Smee, in an article “Mind the Gaps; What’s Missing in the New Wing” wrote that “It’s also missing anything significant by Twombly and its Philip Guston (an artist closely tied with Boston) is large, but poor.”

I agree but there is more to the Guston story. During the 1970s Guston, who after years of abstraction had returned to expressionist figuration, was teaching at Boston University. He was commuting weekly from New York. Taking notice of the MFA he offered them a painting. Moffett was not interested in his current work (it was widely panned at the time by formalists) and asked if he might give an older abstraction. Guston, it appears, was miffed. At the time, the museum had the pick of the studio. By waiting too long it ended up with what Smee correctly identifies as a lesser example.

In carving out The Art of the Americas we question the intent of the museum to focus on what has been created in Boston from Colonial times to the present. Museums vary in their strategies of telling the tale of local art. It is often a touchy subject. Museums in Chicago, New York, and Cincinnati seem to embrace their traditions while Boston runs hot and cold.

Other than a handful of major centers the communities served by most American museums do not entail major artists. If you consider the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT, include the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Mass. College of Art, and widen the reach to the Rhode Island School of Design the MFA is at the epicenter of a major creative community. It has its greatest strength in photography and studio furniture. There is also a notable passion for paint.

Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art was founded, in 1936, as a kunsthalle. Which is to say that it exhibited but did not collect. If it had acquired a fraction of what it showed, and had a community to support it, the ICA, today, would have a collection comparable to that of MoMA. It has started to collect only since opening its new building.

If the ICA didn’t collect the art of our time then the MFA felt no such responsibility. Also, by the mid 1930s, when the ICA was founded (at first as the Boston Museum of Modern Art) the emphasis had shifted. Gallery 223 of the new wing is devoted to the mild and saccharine Brahmin painters of eratz impressionism known as The Boston School. During the Depression years, however, the tougher Boston Expressionists emerged. The leaders were immigrants and Jews including most prominently Jack Levine, Hyman Bloom and Karl Zerbe. Both Bloom and Levine, who reached their 90s, died recently.

Although the MFA paid scant attention to American Modernism, that changed with the acquisition of the collection of William H. and Sandra Lane. In addition to depth in O’Keeffe, Stuart Davis, Arthur Dove, Charles Sheeler and vintage photography the collection included a single great painting, a “Cadaver” by Bloom. It is currently on display. A painting by Zerbe “Job” is included in the 360 page catalogue “The New World Imagined: Art of the Americas.” But the index reveals that Levine is not even mentioned. Considering that he is widely viewed as one of the most important Boston painters of the 20th century the omission is ignorant and insulting.

Of course from the perspective of 3,000 years of the Art of Americas the Boston Expressionists are a minor footnote. But why devote a gallery to the decidedly mediocre Brahmin Boston School and utterly ignore the far more interesting and influential Boston Expressionists? It is an issue which has long defined the elitism and arrogance of the MFA’s founders and traditional supporters.

It was a question I put to both Malcolm Rogers, the MFA’s Director, and Elliot Bosworth Davis, Chair of the Art of the Americas.

I reminded Rogers that Levine had died just the week before the MFA opening. The museum owns a couple of his works, nothing major. It would have been fitting, if not good politics, to hang one. Even at the last minute. Rogers, tap dancing, mentioned that a Levine had for a time been hung in his office. Then he admitted “You’re right, we should hang one.”

During an exchange with Davis I broached the subject of Levine and the Boston Expressionists. She informed me that she was well aware of the issue and the subject of Boston Expressionism was one that she and her staff of curators have discussed. I asked if she was aware of the stash of juvenilia by Bloom and Levine at the Fogg Art Museum? Again, she responded that she knew of the depth of that holding. She agreed that an in depth exhibition of Boston Expressionism is long overdue. Davis stated that it is a matter of doing it properly and finding the right curator. We might also remind Davis that the poet and artist, Kahlin Gibran, lived and worked in Boston.

Over the past few decades, and the 16 years of the tenure of Rogers, the interest in, and acquisitions of, modern and contemporary art have been quirky at best. As the newest department, contemporary art lacks the deep pockets and earmarked funds of other, older and more venerable departments. At the negotiating table for acquisitions curators are hardly equal. With no endowment, contemporary, in general, is dependant on the kindness of strangers.

But there is more in storage than meets the eye. Before he became director of the Guggenheim, for a time, Thomas Messer was the director of the ICA. The ICA moved from its disaster of a home on Soldier’s Field Road to be quartered on the second floor of the Museum School. The plan was for a merger with the MFA as its contemporary department. Messer “advised” on acquisitions including a major painting by Boston born, David Park (1911-1960). He was a key member of the Bay Area Figure Painters.

The planned merger was nixed when Perry T. Rathbone took over as director, moving from the St. Louis Art Museum, to the MFA. Perry, a dilettante at best, and friend of Max Beckmann who painted his portrait, dabbled in modernism. Rather like Malcolm. History repeats itself.

There was a hopeful window. Moffett, who collected Color Field Painting in depth, as well as a pair of important sculptures by David Smith, was forced out. By then the tide had turned on Formalism. But he was replaced, good grief, by Amy Lighthill, a feisty but mediocre curator, who has since left the field. She came under the wing of Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and their taste ran to realism. Stebbins was behind acquiring “Troubled Queen” as well as an important painting by Anselm Kiefer. But they also acquired major examples of the Northampton Realists: Gregory Gillespie, Frances Cohen Gillespie, Jane Lund, Scott Prior, and Randall Diehl. The Alice Neel “Linda Nochlin and Daughter Daisy,” on view in the new wing, dates to that period.

After the Lighthill disaster, Alan Shestack, brilliantly, stole Kathy Halbreich from the List Visual Arts Center at MIT. She soon departed to become director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. Currently, she is at MoMA. Her assistant, Trevor Fairbrother, was elevated as curator but left when Rogers arrived. Enter the mediocre Cheryl Brutvan now gone.

The squeaky wheel gets the grease. Rather like having a loved one in intensive care you have to be there to battle with doctors on behalf of the patient.

Arguably, the MFA founded its contemporary program, one of the last acts of Rathbone, after the museum was freaked out by a guerrilla attack. The Smart Duckys (Todd McKie, Marty Mull and friends) staged a surprise exhibition and reception “Flush with the Walls” in the Men’s Room of the MFA. Diggory Venn, head of education for the museum, flipped out when he went to take a pee. Fearing more attacks, a couple of days later, Rathbone called me at the Herald Traveler to announce the appointment of Moffett.

Similarly, Dana Chandler, Jr., an African American protest painter of the 1960s, put a hurt and mojo on director Jan Fontein and the MFA. The museum embraced The Museum of the National Center of African American Art, then a branch of the Elma Lewis School, as a department of the MFA. Edmund Gaither curated the MFA exhibition “Lamp Black: African American Painters from New York and Boston.”

It is an area that the MFA has continued to pay attention to. During the recent press conference, Davis responded to a question stating a close working relationship with George Wein, the founder of the Newport Jazz Festival. He and his late wife, Joyce, collected major African American artists and Wein is offering key works to the museum.

She also fielded a question about contemporary Native American artists. Several works, including two drawings by the seminal Jaune Quick to See Smith, are included in galleries devoted to historic Native American objects. Davis stated that they are hung in that context because the artists embrace and identify with those traditions. She did not preclude acquiring major works to be shown in the yet to be rehung contemporary wing.

Until the recent completion of a new wing there was a token display of Ancient America. We were astonished by the depth and quality of the Lower Level galleries. Examining the labels we observed that many choice pieces were loans from Landon C. Clay. It was an illustration of the concept that if you build it people will come.

We are still not clear or convinced exactly what Rogers and Davis mean by The Art of the Americas. What is now on view is a bold, one might say, outrageous beginning. It will take time to flesh out all of the areas that are now just hinted at. Other than Guston, there is no Canadian art to speak of. The MFA will have to look into the 1948 manifesto of Refus Global signed by Paul-Emile Borduas and 16 others. The museum must acquire paintings by Borduas and Jean-Paul Riopelle, as well as, Guido Molinari, Claude Toussignant, Francoise Sullivan, Betty Goodwin, and Michael Snow. Just for starters.

Who knows, yet again, the MFA may get lucky. Like when Martha Catherine Codman and Maxim Karolik asked Rathbone for advice on what to collect. He suggested then obscure and cheap American landscapes of the post Civil War era. Until then, nobody cared much about Martin Johnson Heade or Fitzhugh Lane. Today, their works are rare and priceless. The Karoliks, he was an opera singer half her age, also collected American folk art.

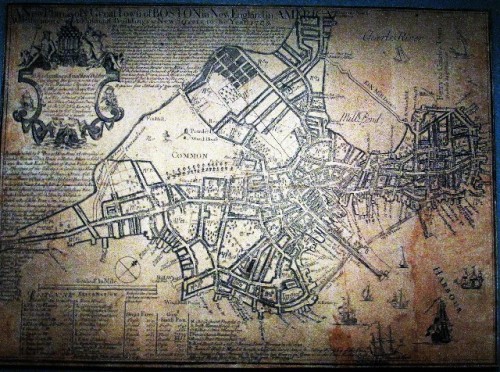

The average visitor to the MFA’s Art of the Americas wing will be blown away by an abundance of riches. We asked Rogers and Davis how many Copleys are now on view? It seems some 30 of a holding of 60 plus. The masterpiece is “Watson and the Shark” of which there is an identical copy in the National Gallery. Add to that Colonial portraits by John Smibert and Robert Feke. There is a plethora of paintings by Sargent including the masterpiece “Daughters of Edward D. Boit.” Lovers of Mary Cassatt will be thrilled. There are Homers to die for. It goes on and on through 53 galleries.

It is planned that many of the galleries, such as the one devoted to photography, will be rehung on a six month cycle. Here and there individual works will be switched. Over time we will see more of the roughly 50% of the collection not on view. Rogers assured us that there are no masterpieces in storage. But perhaps there are some surprises.

There was a lot to take in. We noted new works and indications of areas of interest. In 2001 Erica E. Hirshler curated “Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870-1940.” In honor of Maud Morgan, born a Cabot, the MFA has an endowed prize awarded to mid career Boston women artists. Although the funds exist the prize has not been given for the past four years. Scott Prior appears to be the only regional artist currently on view in the new wing.

We noted token works by American Regionalists including John Stuart Curry and two paintings by Grant Wood on loan from the William I. Koch collection. It was a surprise to see a Norman Rockwell on loan from his museum in Stockbridge. The painting was hung near a loan of a work by Andrew Wyeth.

There were no examples of the Social Realists of the 1930s or the Mexican Mural painters. According to the MFA we never endured the Civil War, World War I or World War II. We could go on but you catch the drift.

Yes there were a couple of nice paintings by Eakins. But you have to visit the Philadelphia Museum to see his work in depth. Travel to St. Louis for George Caleb Bingham. The Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, for John Trumbull. Cincinnati for William Merritt Chase and Frank Duveneck. Denver for Ancient America and Native American Art. Memphis for Elvis. Chicago for Grant Wood and the Regionalists. The Freer in Washington, D.C. for Whistler. We found a lot of David Gilmour Blythe and John Kane at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. For contemporary African American artists visit the Birmingham Museum or the Wadsworth Athenaeum for vintage works. Andy Warhol’s museum is in Pittsburgh while Norman Rockwell’s is located in Stockbridge. Houston has the Rothko Chapel. Dartmouth College is home to the Orozco frescos in its Baker Library. Don’t miss Marfa, Texas for Donald Judd and Dan Flavin or Mass MoCA for Sol LeWitt.

For a taste, snacks of all of the above, visit the MFA. It’s positively awesome.