Clyfford Still Unfolds in the Rockies

A Stand Alone Museum for Still Opens in Denver

By: Susan Hall - Nov 18, 2011

The Clyfford Still Museum

Denver, Colorado

In downtown Denver, Clyfford Still's stand alone museum rises out of the prairies with a Rocky Mountain backdrop. His work of a lifetime has come to light in a Museum facing north, the preferred setting of a painter's studio.

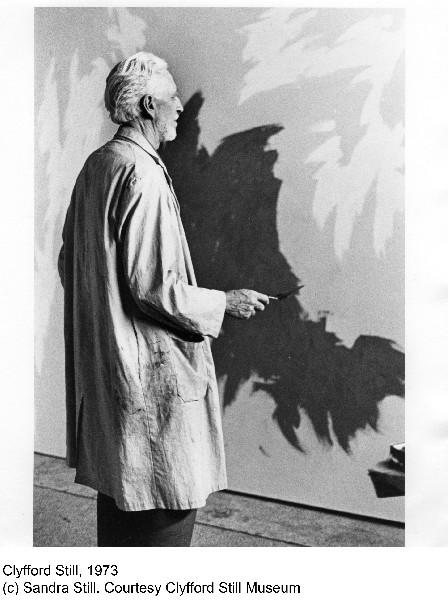

Every major American city in the US wanted Still's paintings, created after he arrived at a farm in the Maryland countryside and many even earlier. Retiring from New York in 1961, Still continued to paint for the last two decades of his life. San Francisco and the Albright-Knox in Buffalo held more of Still's work than anyone else, including the Museum of Modern Art which Still disdained. Most of his work was rarely seen.

Still may have disappeared but no one forgot him even as he absented himself from an art world he loathed. His peers, including Jackson Pollack and Barnett Newman, declared Still the freshest and least academic among them. "A bolt out of the blue." Still's paintings left Mark Rothko "breathless."

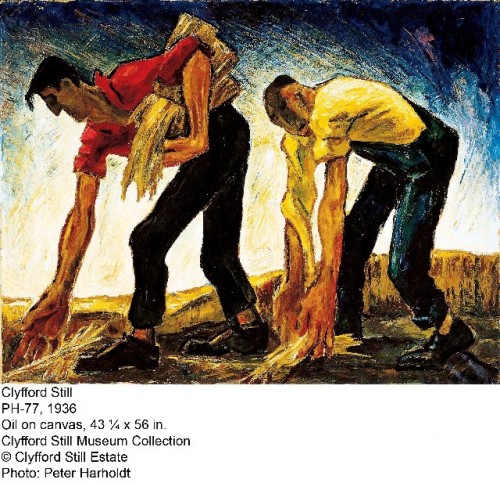

When Still died in 1980, he left a one page will stating that his entire body of work, 2,403 pieces, would be given to one American city if it would commit to a stand alone museum housing only his work. The museum would be a place where people could go and contemplate the earliest representational studies, some of which look like a harsher Thomas Hart Benton, on to the highly abstract summaries he painted toward the end of his life. Still was a master. The magnitude, beauty and power of his work will now begin to be seen.

Denver won the bidding after propositions from Baltimore, Mass MoCA and others were rejected by Mrs. Patricia Still for 20 years. Finally Mrs. Still wrote a short note to her nephew, Curt Freed, a prominent Denver physician, and inquired about Denver as a possible location for the Museum.

When John Hickenlooper, a Philadephia Quaker by birth, became Mayor of Denver he decided this one man museum would be a perfect fit with the city. In Washington, DC for a Mayors' Conference, he cancelled a private appointment with the President to go to Maryland and discuss the Museum with Mrs. Still. A well-read and thoughtful man, Hickenlooper is a co-owner of Denver's iconic bookstore, The Tattered Cover. He won Mrs. Still's heart and her husband's collection for Denver.

Interestingly, when Patricia Still died a year after the deal was struck, Denver was surprised to find itself the principal beneficiary of her personal art collection. With relative ease, the city was able to put four of her Still paintings on the auction block. They sold this week for 114 million dollars. Denver had privately raised 30 million dollars to build the Still Museum. This fat bonus provides a financial cushion which will enable the city and curators to do whatever seems important to fulfill the artist's wishes about the exhibition and enjoyment of his work.

Still's daughters Sandra and Diane have worked with the architect, curators and conservationists to make this a perfect one artist museum. More excitement surrounds its opening than other museums devoted to the work of Andy Warhol and Georgia O'Keefe, for instance. All of Still's most important work is here. Often solo museums have leftovers.

Not a detail has been left to accident. Barbara Ramsay, who has been charged with the conservation of paintings which were often rolled up, talked the Getty Museum conservationists into undertaking the restorations for free.

The architect Brad Cloepfil and Allied Works Architecture succeed splendidly in the daunting task they undertook. A ceiling lattice of ovals cast in cement provides mottled light throughout the nine gallery areas on the second floor of the building. A space separating the geometric ovals from the skylights above houses shades which can be pulled across when the direct light becomes too harsh or intense.

The museum cast from concrete is firmly set in the earth. The slabs of concrete which form the walls were poured into sheets of tree trunks and other forms of nature to create textural variety. They provide an unexpected warmth. The layout of the nine galleries often lets you gaze at a distant room and a distant painting to give an unaccustomed perspective. Still wanted the viewer to have an intimate experience, possible now with each step you take. The intimacy, however, is contrasted with the grandeur of the works.

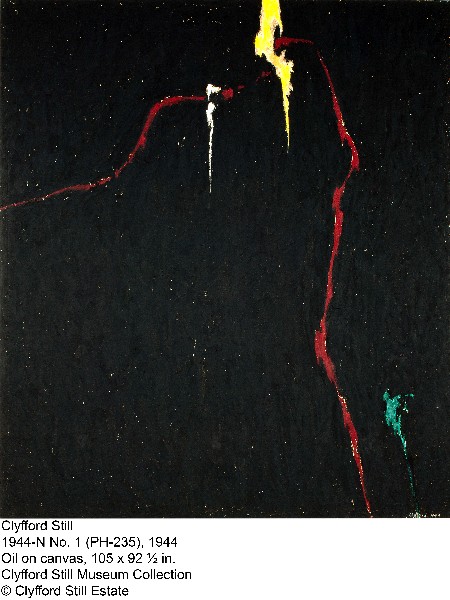

For insights to the complex work we prefer to allow the artist to speak for himself. He wanted each viewer to have his own impression. More of his own interpretation may become apparent when the archives including letters and notes are plumbed by scholars. For now, we have comments Still himself made over the years. He set out to "cut through the opiates of the past and present to get direct, immediate and free vision." "I never wanted color to be color. I never wanted texture to be texture, or images to become shapes. I wanted them all to fuse in a living spirit." "These are not paintings in the usual sense; they are life and death merging in a fearful union. As for me, they kindle a fire; through them I breathe again, hold a golden cord, find my own revelation." "You can turn the lights out. The paintings will carry their own fire."

These paintings linger in the mind's eye. The promise of ever changing exhibits, the prospect of seeing the almost 2300 works that are not on view, makes me want to move in for a while and gaze and contemplate. That's how successful the work of art that contains these incredible works of art is. That is how much in touch with Still's vision the curators Dean Sobel and David Anfam are.

Denver reflects Still's perspective. The city sits on plains rolling in. To the west, the Rockies jagged peaks jolt us. The cloud formations with rough edges are often thin, oblong shapes which settle into the landscape. Still's paintings are surely as vast as the Big Sky, their figurations like the western landscape, harrowing and gorgeous at once. A perfect setting.