Does Art Matter

In the Eye of the Beholder

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 18, 2012

De gustibus non est disputandum.

On rainy summer days Mom took us antiquing or to the galleries and gift shops of Rockport.

We were told “Look but don’t touch.” Adding “If you break it you buy it.”

The landscapes and seascapes of the Rockport School and the Cape Ann Art Association amazed me.

My father, a surgeon, took his first painting lesson from a family friend, the art dealer and artist, John Castano. He was our weekend guest and together they rendered the Annisquam Light House not far from our home in Norwood Heights.

It was a subject Dad would return to many times over the next decades.

There were many artists he took classes with. As a youngster I joined him during a well attended, bravura lecture demonstration by Emile Gruppe. We owned a few of his paintings. A rather dark and mawkish view of Gloucester Harbor hung over the mantle in our dining room. It was described as having been bought cheap when the artist was still a drunk.

It was my first glimpse into the bohemian nature of artists.

Later, in high school, when my taste became more sophisticated than that of my parents, Dad had a medical explanation for modern art. Picasso painted that way because he, like all the rest, suffered from syphilis.

It rots the brain which results in Cubism.

Later, after freshman year in college, I announced that I was giving up pre-med and planning to major in art. Dad, who grew up in the mean streets of Brooklyn and had a life long passion for boxing, dragged me out to the back yard. Ripping my shirt off he was intent on beating some sense into me. Mom and my sisters broke up the fight.

Over spaghetti and cannolis it was decided that I could major in art but Dad officially disowned me. No way was he going to support my bohemian lifestyle.

While Mom never had Dad’s talent for art, music, and cuisine she took up painting. She took classes and loved making landscapes.

Years ago I gave a party in my crowded Cambridge apartment. By then I had a modest collection.

My art critic friend, David Bonetti, studied the prints and then asked “Who’s Flynn? You seem to have collected this artist I never heard of in depth.”

“My Mom” I said.

To me her paintings are beautiful.

As an art critic there is no way I can defend them.

Or the Thomas Kinkade that hangs in the reception area of a local office.

During a recent dinner party we discussed the kitsch of Kinkade “The Painter of Light” with artist friends.

It was part of a dialogue about easy art.

Those safe landscapes, still life paintings, and “abstracts.”

Understandably, and perhaps rightly, I was denounced as a snob.

Defending myself I stated that art can be an idea. Or an action.

It doesn’t even have to be visible.

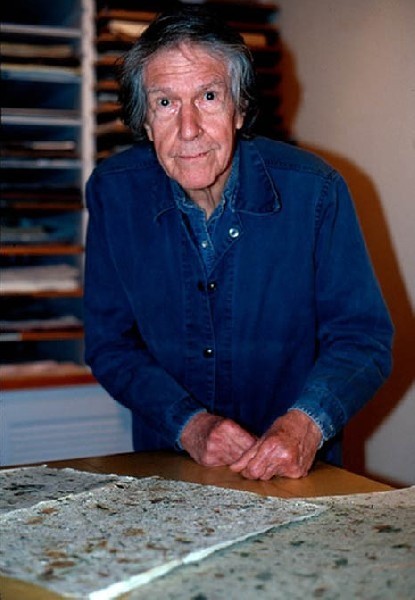

I tried to explain how John Cage’s famous 4’33,” or four minutes and thirty three seconds of silence, was “music.”

That was a tough sell to our dinner guests.

It was “performed” by David Tudor as a part of a Cage video shown during the first classes of my annual Avant-garde seminar at Boston University.

Students are amazingly conservative.

The discussion after the Cage video always devolved into a verbal brawl. The more upset the students became the more fertile the exercise.

It incensed them all the more that I was amused by their outrage.

"That's not art" was the mostly concensus opinion.

I love Cage. He was such a charming and puckish provocateur.

Well, at least the idea of Cage. And Merce Cunningham his collaborator.

We were so fortunate to see the company at Jacob’s Pillow during the weekend when Merce passed away. They toured for two years after that and are now disbanded.

Even knowing what Cunningham/ Cage were all about that performance at Pillow was so challenging. It was a very difficult review to write. Until his last breath Cunningham’s work was a conundrum. While the choreography is no longer performed its legacy is indelible.

Which cuts to my primary notion about art.

No pain no gain.

Art that too readily gives up its secrets has little or no holding power on the psyche.

What you see is what you get.

Eye candy may pack visual calories but it lacks nutrition.

As an undergraduate at Brandeis I took a seminar on Caravaggio with the brilliant professor Creighton Gilbert. Previously I had taken his seminar on Michelangelo.

A later graduate seminar on Michelangelo, with BU professor Helmut Wohl, paled in comparison to Gilbert’s.

Prior to Creighton’s seminar, I had never heard of Caravaggio. Gilbert’s approach was amazing. We started with the early known works, the juvenilia. Looking intently we discussed them until there was nothing left to say. Which proved to be a lot.

That established a critical vocabulary. For a seminar report I researched the “Candlelight Painters” of Utrecht. Some had been to Italy and returned with Caravaggio's influence. Through osmosis, Rembrandt, who never left Holland, absorbed his dramatic use of chiaroscuro. As did Georges de la Tour in France.

Since the 1960s, we have come to know a lot more about Caravaggio. Gilbert was prescient in bringing to us one of the most complex and influential artists of the baroque era. Gilbert participated in Walter F. Friedlaender’s seminar, the first on the artist, at The Institute of Fine Arts at NYU. There was even an interesting early reference to Caravaggio in a novel by Aldous Huxley which Creighton brought to our attention.

There were no courses on modern art at Brandeis at the time. Although Sam Hunter, who wrote the text book on modernism (with Jake Jacobus) I used for years as a professor, was the founding director of the Rose Art Museum. Like church and state there was separation between the museum and the fine arts department.

Sam founded the renowned collection which Brandeis wanted to cash out recently. Through the Poses Foundation Sam mounted amazing colloquia and brought the New York School to Waltham. I vividly recall a lecture by Robert Motherwell. Who will ever forget the Rose opening when the champagne flowed and Larry Rivers play sax with his jazz band. When Bill Seitz was the Rose director he invited me to lunch with Frank Stella. While Stella mostly mumbled Bill answered for him. When Carl Belz was director I spent an afternoon with Helen Frankenthaler while they were installing her exhibition of works from the 1960s. Other than Mountains and Sea, which was not in the Rose show, her work was decorative and boring.

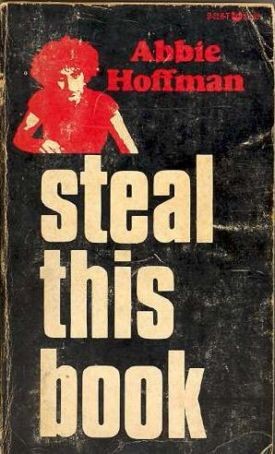

The art department was conservative toward contemporary art. The head of the studio program, Mitchell Sipporin, was an illustrative social realist. The mantra of the university, however, was radical. That was most evident when Brandeis students Angela Davis, Susan Saxe, Kathy Powers, and Abbie Hoffman made the FBI’s list of “Ten Most Wanted Criminals."

That zeitgeist filled our hearts and minds with a fervor for dissent. The mandate was to think and act counter to the mainstream. To accept and initiate change, embracing the avant-garde. While never loosing the lessons of classicism.

As Thalia Howe (wife of Irving Howe) conveyed in a wonderful course on Ancient Greek Literature, all of theatre conforms to Aristotle’s Poetics with Oedipus Rex as the paradigm of drama.

You have to know and feel that in your heart before you can deal with Cage, Cunningham or Duchamp.

It is never a matter of abandoning the arts of the past for those of the present and future. It is more like the ever expanding universe. We embrace new art forms and technologies but it doesn’t make us smarter or more capable of feeling and understanding. The art of the present, while progressive, is not an improvement on the arts of the past.

Arguably, there is no more perfect work of art than the Venus of Willendorf.

The BU classes were always exciting. It was fun to note transformations as the weeks progressed in the seminar. The evenings started with a video- Chris Burden, Jeff Koons, Robert Rauschenberg, Frida Kahlo, Basquiat, or a drama, Waiting for Godot, Six Characters in Search of an Author, jazz like Miles Davis and John Coltrane, or the Sex Pistols.

Like Gilbert’s seminar we would discuss until there was nothing left to say.

Gradually, you felt the students absorbing and even anticipating what Robert Hughes described as “The Shock of the New.” They got more adept at the game and less easy to trick into outrage and protest. The trope of offended resistance became ever more obvious and mutated. Eventually, there was less and less resistance to radical ideas replaced by interest and curiosity.

There is, however, the ennui of the avant-garde, if the term is even still relevant.

Through the efforts of countless professors, at so many art schools, there are now legions of initiates into the mandates of radical art practice. If you have the seven league strides for the biennial and art fair circuit it’s a global, and dare we say this, enervating phenomenon.

The King is dead. Long live the King.

A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse.

Perhaps the quantum growth of that ever expanding universe of art possibilities has unseated and unhinged us.

There was a time when it was possible to narrowly define and understand the isms of modernism and contemporary art.

Advanced art criticism and theory have now abandoned all hope of clustering and grouping individual artists and movements. The resultant tenure track art speak has grown accordingly ever more intricate and arcane.

Heaven help the artist, curator, or critic who lacks fluency in the lingua franca of art speak.

We are subsumed by the hegemonic powers of a cabal of mega gallerists and their client collectors.

Remarkably a former New York gallerist " Jeffrey Deitch, closed his SoHo gallery in the spring of 2010 to become director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, an institution with an enviable curatorial record but historically plagued by financial problems. Criticism about his tenure has been constant, but has intensified over the last three and a half weeks in the wake of the departure under pressure of Paul Schimmel, the museum’s brilliant, headstrong chief curator, after a vote by the trustees. The chemistry between the two men was known to be troubled." Roberta Smith, the New York Times

What a critic writes about the work is of trivial significance compared to what the work in question commands particularly in the secondary market. Critical evaluation doesn’t stand a chance compared to the net worth of a work of art.

Since the death of Clement Greenberg no critic has commaned the status and ability to influence the art market.

If inventory piles up in the studio, the message is that the artist is more or less worthless.

Why bother to make work that doesn’t sell? Or even attract a whisper of critical attention?

Then there is all that easy Rockport art that sells. It may bring visual comnfort and decoration to an office or living room but has no consequence in critical discourse.

In the fame game all but a handful of artists come out on the short end.

If art can be an action or idea, ok, how do you sell it?

The philistines have invaded the temple of art.

Including museum directors like Tom Krens, who showed Armani and motorcycles at the Guggenheim, or the vulgarian, MFA director, Malcolm Rogers, displaying the cars of Ralph Lauren and the glass baubles of Dale Chihuly.

As we have stated Look But Don’t Touch.

There is no way that most of us can own what we see and visually crave. It takes deep pockets to jet to art fairs and biennials. Or see all of the world's great museums and monuments. Time is running out on the opportunity to stand before the Pyramids, the Parthenon, Hagia Sophia, Taj Mahal, the temples of Kyoto, or explore that last great museum on my list, The Hermitage.

This spring we plan to visit Dublin and its Trinity College with the Book of Kells. Actually, I saw the wonderful medieval books some years ago when the MFA hosted Treasures of Irish Art. Similarly, I have by now seen most of the Caravaggios except those in Malta and Sicily which don’t travel. I swooned over The Supper at Emmaus at Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan a few years ago. It recalled how my heart stopped still the first time I saw Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina and Apollo and Daphne at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. The museum also owns the fascinating Sick Bacchus by Caravaggio.

You can die and go straight to heaven in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

This underscores the elitism, the social-economic inequity of the visual arts. Perhaps it equates to why the fine arts tend to interest a tiny percentile, the domain of the infamous one percent.

We live within walking distance of Mass MoCA one of the great contemporary museums in North America. Not far away is the superb Clark Art Institute.

These remarkable museums draw about 150,000 visitors each year. Before its move to the waterfront, the old Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston averaged about 25,000 annual visitors. It took decades for the MFA to reach half a million and then a million.

While I can’t own the works I see in the great museums I have a collection of some 7,500 LPs. I can possess and listen to whatever I like from Bach to Miles Davis. One can afford lawn seats at Tanglewood to hear world class music. There are half price tickets to Broadway. It costs us $6.50 (senior price) to see a James Bond movie that cost $200 million to make. Cable TV and the Internet provide an amazing range of videos, information, and communications.

There are even ways to hack and download music and videos for free. Pirated DVDs often are circulated before movies are even released.

That doesn’t really bother me. Kind of like Abbie’s “Steal This Book.”

But I was pissed the last time in Vienna when I asked a guard where to find the Salt Cellar of Cellini. One of its greatest treasures which I had so enjoyed during a prior visit.

“It was stolen” was the numbing answer.

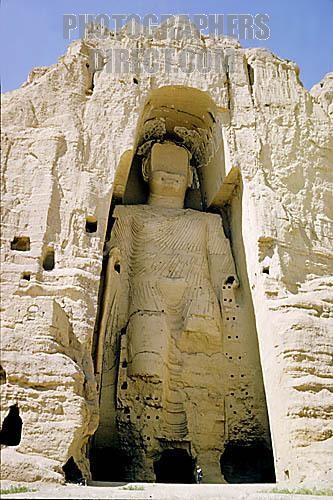

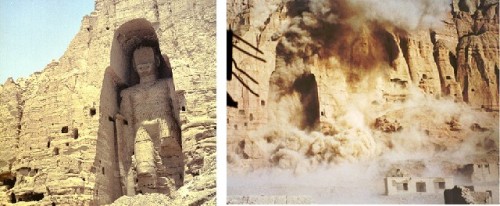

It’s horrifying to consider that an ersatz Captain Nemo enjoys viewing purloined masterpieces in his or her submarine. Great art belongs to all of us. It’s about our humanity. How despicable that the Taliban blew up the giant Buddha in Afghanistan. Or that the treasures of the great museum in Iraq were looted during Shock and Awe. It was not a priority for the invading US troops to protect works of art.

Does any of this make sense?

Probably not.

Which is to say that nobody really understands art.

But it was worth me and Dad fighting over.