Michael Tippett's The Midsummer Marriage

Conrad Susa's Transformations

By: David Bonetti - Nov 18, 2012

The Midsummer Marriage

by Michael Tippett

Libretto by the composer

First performed by Royal Opera, Covent Garden, London, 1955

Boston Modern Orchestra Project

Jordan Hall, Nov. 10, 2012

Conductor: Gil Rose

Cast: Sara Heaton (Jenifer); Julius Ahn (Mark); David Kravitz (King Fisher); Deborah Selig (Bella); Matthew DiBattista (Jack); Joyce Castle (Sosostris); Lynn Torgove (She-Ancient); Robert Honeysucker (He-Ancient)

Transformations

by Conrad Susa

Based on poetry by Anne Sexton

First performed by Minnesota Opera, 1973

The Boston Conservatory Theater

Nov. 15 – 18, 2012

Conductor: Andrew Altenbach

Production team: Nathan Troup, stage director; Catherine Malfitano, artistic advisor, Julia Noulin-Merat, scenic designer Lara De Bruijn, costume designer; Carl Wiemann, lighting designer

Double cast with Boston Conservatory students

This past week's productions of two mid-century operas ended up on Boston stages. Michael Tippett’s large-scale “The Midsummer Marriage” was done as a concert work, and Conrad Susa’s more modest “Transformations” was fully staged. With its mythological references, its cave and its staircase to the stars, its mysterious clairvoyant, not to mention the series of three ballets in its second act, which add up to more than 20 minutes of sometimes ravishing music, the Tippett cried out for an all-out production. Alas, it was supposed to have been thus.

The local opera community was all a-buzz when Gil Rose announced that his ambitious modern orchestra project was going to produce a one-night concert version of Tippett’s earliest and most often produced opera, which had never been seen in Boston. The work had been scheduled to appear as a fully staged work by Opera Boston, but when that company shut down because, according to reports, a disgruntled supporter who didn’t get his way picked up his ball and went home, the production died with the company. But, rather than waste the effort he’d put into it, and leave a community curious and disappointed, Rose, who was Opera Boston’s music director, moved it to his own company.

One wishes one could report that the evening was a triumph, but it was not. The fault lay not with Rose, his crack orchestra and the cast of excellent singers he assembled, but in the work that was the subject of all their efforts. What a dud! (In a sense, it is a repeat of Paul Hindemith’s “Cardillac,” also conducted by Rose for Opera Boston, which was fully staged but never came to life.) If this is considered Tippett’s best effort in opera form, please save me from having to endure one of his lesser works. (Actually, I already experienced one! Sarah Caldwell produced “The Ice Break” in 1979, and all I remember it that it didn’t make much of an impression, despite its race riot and the go-go boots the female protagonist wore.)

A full-scale staging of “The Midsummer Marriage” might not have made much of a difference – could anyone save this baby?

Where to start?

Tippett was a real eccentric in a land of eccentrics. Openly gay since boarding school, first a Trotskyist and then a committed pacifist, he did time during World War II as a conscientious objector (unlike his peers Benjamin Britten, W. H. Auden and Stephen Spender, who fled to the United States to avoid the personal inconvenience of saving the world from Adolf Hitler).

He wrote some lovely music, lyrical in the manner of the English pastoral tradition, which has always seemed rather fuddy-duddy, but which now seems prematurely elegiac as we face the destruction of our planet by the forces of greed. Tippett wrote four operas and two large-scale oratorios, but he might have done better restricting himself to smaller scale expressions.

“The Midsummer Marriage” does contain some lovely music – the ritual dances are often programmed as a stand-alone piece, and there are delightful references to Renaissance English music - brass bands, madrigals and courtly dances. But it is encumbered with a heavy and pretentious text, which Tippett wrote himself. Laboring reportedly mightily for six years to bring it to completion, he might have been better off hiring a hack or adapting a previously existing text.

What’s it about?

Oh, don’t bother. As someone once said, it’s a lot of sound a fury signifying nothing.

It’s “about” two pairs of young lovers, one aristocratic, one “rustic,” trying to overcome obstacles so they can achieve their midsummer marriages. That isn’t enough for Tippett – another composer would have written a nice little masque on the theme – he had to get cosmic about it. References to Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” and Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” are reasonable enough given the pairing of lovers and the obstacles to their union, but then he ladles on some T.S. Eliot and a lot of Carl Jung. The whole creaky edifice eventually collapses, and his manhandling of the English language becomes a kind of dark comedy he didn’t intend. By the end of the endless third act I was laughing to keep myself from falling asleep.

Rose conducted the orchestra with real feeling, driving it propulsively and bringing out all the color of its tightly woven sonic tapestry.

The cast was uniformly excellent. As Mark and Jenifer, the aristocratic pair, Julius Ahn and Sara Heaton did their best to bring to life the only remotely three-dimensional characters, giving the evening a touch of human warmth. Ahn displayed a clarion tenor, suggesting a possible future career as a heldentenor. Heaton has a thrilling young soprano voice with real high notes and a fullness throughout her vocal range.

As the “rustics” (in Tippett’s reinterpretation of the standard trope, more accurately “workers”), soprano Deborah Selig as Bella and tenor Matthew DiBattista as Jack, did the best they could with such undeveloped characters, although Selig had an nice opportunity to show off her coloratura.

As King Fisher, Jenifer’s father, baritone David Kravitz, who seems to be in every opera performance I attend in the Boston area, had the steady voice of authority the role and his vocal type demand. The King Fisher is the opera’s villain, and his role is that two dimensional. A representative of the capitalist order, he throws money at the workers’ chorus to show how easily he can buy them off, and he denounces Mark as “a loafer sponging on the state.” Sound familiar?

Baritone Robert Honeysucker as the He-Ancient was impressive in his gravitas; Lynn Torgove, as his female counterpart, the She-Ancient, seemed underpowered. The weirdest performance of the evening was provided by veteran mezzo-soprano Joyce Castle, who as the clairvoyant Madame Sosostris, emerged from her cave on wobbly heels and with a wobbly but still commanding voice.

It’s regrettable that such an eager and able team of musicians couldn’t have been pouring their talents into a work that offered more rewards.

I was going to say that the Susa/Sexton collaboration “Transformations,” was a romp, but that would be insensitive to its material: it is set in a mental hospital (modeled on Belmont’s McLean’s) and deals with the demons that haunted poet Anne Sexton throughout her life. Still, the young cast brought such youthful energy and enthusiasm to their task that you couldn’t help but have a good time.

Sexton, who was born in Newton and lived in Weston, was one of the triad of Boston-associated poets – the others were Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath – who propelled “confessional” poetry into the formalist-oriented American poetry world dominated by the dictates of the New Criticism. Their emotional honesty proved searing to readers at the time, but whether its focus on mental illness still holds any relevance in the age of Prozac and Lexapro remains to be seen.

“Transformations,” the last book published (in 1971) during Sexton’s lifetime - she took her own life, at the age 45, in 1974 - was based on tales by the Brothers Grimm. Sexton wrote 17 poems for it; she and Susa chose ten to set to music. (The evening is a little long – it lasts two hours including intermission – and maybe eight would have worked better.) Some familiar fairy tales – Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Rumpelstiltskin, Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel and Sleeping Beauty – are set along with others not often read in the nursery. Sexton restored the horror and emotional violence the German brothers frankly expressed but which have been smoothed over in subsequent retellings, while adapting the stories to the present and the personal. I read the poems the night before the performance and I can report that I did indeed have nightmares.

The work isn’t really an opera; there is no traditional narrative with an emotional payoff at the end when the heroine dies – although in this case, we can’t help but bring a retrospective reinterpretation to the work after Sexton’s death. It is more a song cycle or even an oratorio, and it might work well presented as either. But the requirements are modest – there is a small orchestra, and many small roles that don’t require voices that would fill the Met – and it is frequently done as an opera by small companies and in music schools, as it is being done here.

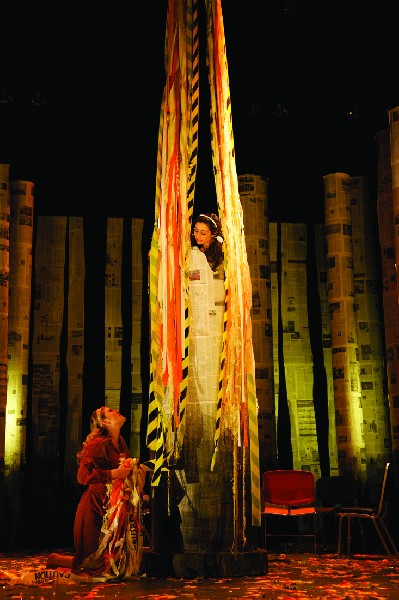

Although staging might not be necessary, it was certainly welcome here in Boston where concert operas and HDTV transmissions dominate the experience. And the staging helped make the evening a success. Set designer Julia Noulin-Merat turned the hospital day room into a forest by surrounding its central space with “trees” made of tall cylindrical forms covered with newspapers. (The forms were moveable and were easily transformed into scenic requirements such as Rapunzel’s tower.) Lighting designer Carl Wiemann made the conceit work with his shadowy lighting, and when the back door opened letting in nurses with their paper cups of medications, the blinding light made it clear that the forest existed in dreamtime only.

Special kudos to stage director Nathan Troup, who reconfigured the cast into solo, duet and group situations with fluidity and grace. What role the great singing/actress Catherine Malfitano, who sang in the work’s premiere in Minnesota, played in making this all work, I don’t know, but I can imagine that she might have something to do with the evening’s heightened theatricality.

Susa seems to have been happy enough writing music that plays the supporting role to Sexton’s words. He and Sexton, who worked together closely, showed amazing skill at turning her poems, written for one voice – the poet’s – into a work for an ensemble of singing actors. Susa’s vocabulary is amiably modern, and his small orchestra includes clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, trombone, percussion, electric organ, piano and a single string instrument – a bass – a combination that easily evokes both jazz and jazz-oriented modernists like Kurt Weill. Still, it was difficult to hear most of the words sung, even though several of the performers had excellent enunciation, and much of Sexton’s cynicism and wit got lost. Supertitles would have helped.

Andrew Altenbach led the orchestra with verve and spirit, and the cast of eight, each of which took several roles, was charming. Perhaps a little too charming in that the real terror behind the tales and Sexton’s poetry got glossed over. No harsh judgments – this was student production after all, and the smooth results speak well of the training music students receive at the Boston Conservatory.