Ana Mendieta at London's Hayward Gallery

Outstanding Among Feminist Museum Exhibitions

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 19, 2013

Most of the modern and contemporary art museums that we visited recently in Dublin and London, with the exception of Paul Klee at Tate Modern, featured women of varying degrees of obscurity, in their special exhibitions.

These included: Leonora Carrington: The Celtic Surrealist and Eileen Gray: Architect Designer Painter at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (through January 26), The Brazilian artist Mira Schendel (to January 19) and Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair (closed November 17) at Tate Modern, the only female member of Arte Povere, Marisa Merz, at Serpentine Gallery (through November), Sarah Lucas: SITUATION Absolute Beach Man Rubble at Whitechapel which we didn’t get to visit (Through December 15).

An exception was the lively Pop Art Design at Barbican through 9 February 2014. We also saw Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna, 1900 at the National Gallery through 12 January.

The dominance of feminist reclamation projects in museums may be an overcorrection and swing of the pendulum after centuries of neglect. But this curatorial adjustment may be out of sync with the art world or the interest in niche explorations by audiences.

During our full day at Tate Modern, which is currently undergoing renovations and expansion, we found that the enormous Paul Klee retrospective with numerous small works was mobbed, while the exhibitions of works by Mira Schendel and Saloua Raouda Choucair (curated by Jessica Morgan formerly of ICA Boston) were sparsely attended.

While admission to Tate Modern is by voluntary contribution the special exhibitions are not. Visitors were willing to pay to see the work of Klee but apparently balked at paying to view work by unknown artists.

For the Tate this appears to be a counterproductive policy. It’s fine to charge for Klee but the other shows should be free to the public. This is work that should become more familiar. Isn’t that the point?

I was pleased to see the work of Schendel a serious abstract artist who adds dimension to the very interesting Brazilian scene which we are becoming ever more familiar with. The exhibition of paintings and sculpture by Saloua Raouda Choucair, unfortunately, was tedious and dull not reaching the standards of a renowned museum.

Whatever the social and political curatorial incentives it is imperative that there is a strong aesthetic rationale behind exhibitions in major museums.

The special exhibition Ana Mendiata:Traces at Hayward Gallery through 15 December met all of these criteria and then some.

The generous retrospective of the Cuban born artist (18 November 1948) was compelling, insightful and often gut wrenching.

At the time of her death (8 September 1985) Mendieta was not well known beyond the inner circles of the New York art world. She was found dead some 34 floors below the apartment she shared with her husband, Carl Andre, a minimalist sculptor.

During dinner in a restaurant that night they were observed drinking heavily and arguing. When police arrived Andre was found incoherent in an apartment that included a number of empty champagne bottles.

A sensational trial for murder, often compared to that of O.J. Simpson, resulted in a verdict of not guilty.

In her retrospective there are numerous uncanny works that evoke rape, violence to women, and murder.

A familiar triptych of three works on paper depicts bloody hands and arms dragged down in outward Vs. There is a poor quality video, among a number in the exhibition, showing her making the iconic works. The drawings were readily familiar from the collection of the Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University. They were a part of an exhibition, including a Mendieta candle piece, organized by former curator Susan Stoops who is now with the Worcester Art Museum.

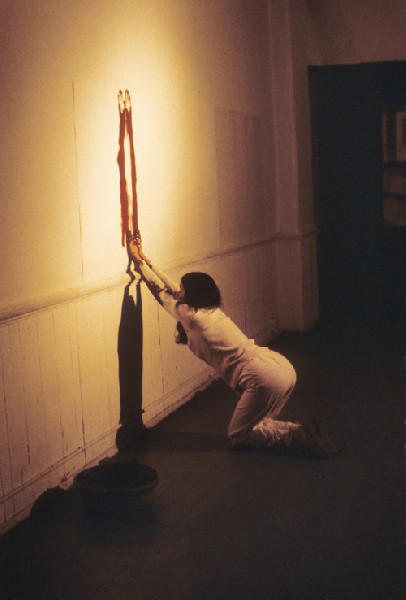

This riveting overview enforces that Mendieta was a conceptualist and site specific artist with seemingly little interest in making saleable work. Today, however, the archival documents, photographs, drawings, and artifacts are of enormous aesthetic and monetary value.

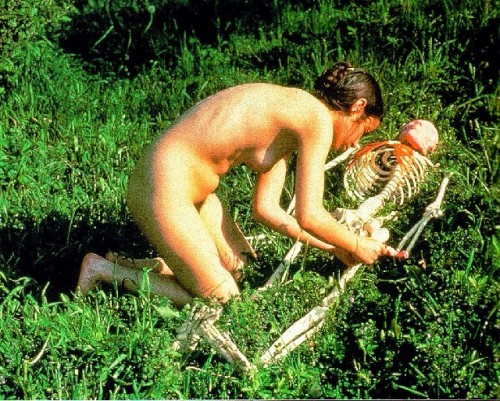

It is remarkable that so much of the work was temporary and ephemeral or created in remote locations which are now pilgrimage destinations and shrines for votive offerings. Her transient materials included piles of leaves, burned out pits in the shape of primal women, mud, sand and swampy settings.

Even the documents, now fading and distorted color photographs, are proving to be ephemeral. One wonders if the estate would allow curators to make archival prints from the original slides or Photoshop and reprint the photographs. They are now so out of kilter that it is a distraction.

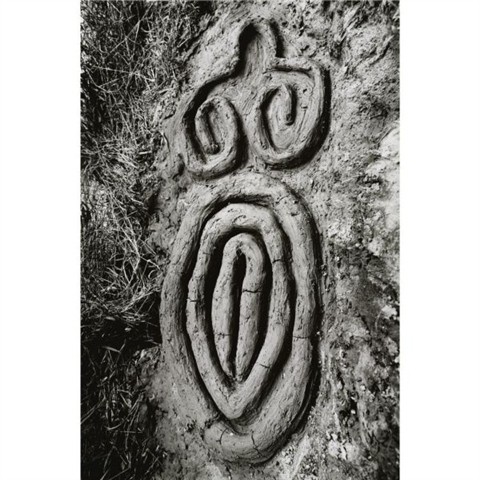

So it was a revelation and relief when we moved on to a gallery of large, superbly printed, black and white enlargements of her ersatz Neolithic rock carvings. This all the more resonated with us having just visited such sites as Newgrange (3200 BC) and an ancient burial site on the lunar landscape of The Burrne in Ireland. The pre Celtic carving of those and other monuments resonate with the primal women of Mendiata’s ritual carving, graves and monuments.

She was striving to evoke the humanistic essence of the earliest depictions of mankind. Initially, they almost entirely rendered rotund fertility goddesses. The earth mothers reflect theories that the earliest communities were matriarchies.

The Silueta Series comprised transient works of the 1970s surviving in film and video documentations. In addition to primeval sources she also employed the Santeria rituals of her native Cuba. She was taken to the U.S. at the age of 12 but retained her Cuban heritage. It was while a student in Iowa that she found her own way, mandate and identity as an artist.

Today, her work is indelibly fresh, current and visceral. It is arguable that the art world has caught up with her agenda which included gender and identity.

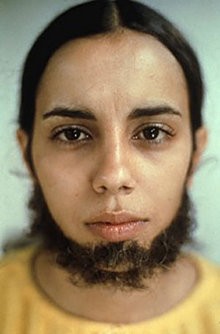

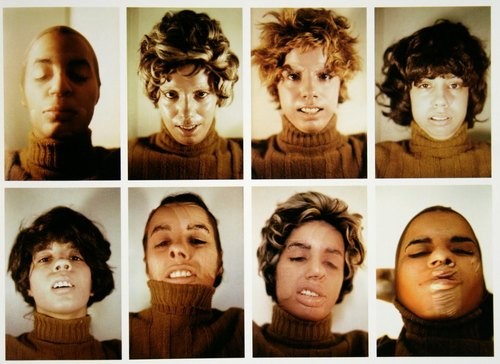

Just as Marcel Duchamp developed a female identity as Rrose Sélavy there are photographs of Mendieta with moustache or whiskers. In a series of images she plays with personas and disguises.

There are many aspects of her body work.

In a series I was previously unfamiliar with she smashes her body against flattening panes of glass. There are numerous images of Mendieta as a forest goddess covered with mud and merging with the spirit of a tree. Or lying naked in the landscape.

Overall, it is outrageous, radical and riveting work. We staggered out of the exhibition completely shattered by its power and impact.

Mendieta takes no prisoners and needs no excuses to be seen, respected and appreciated.