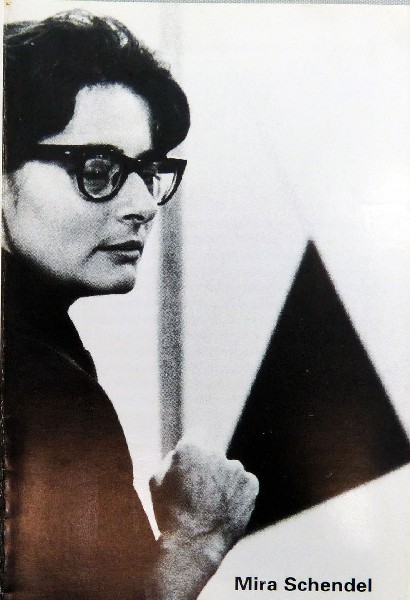

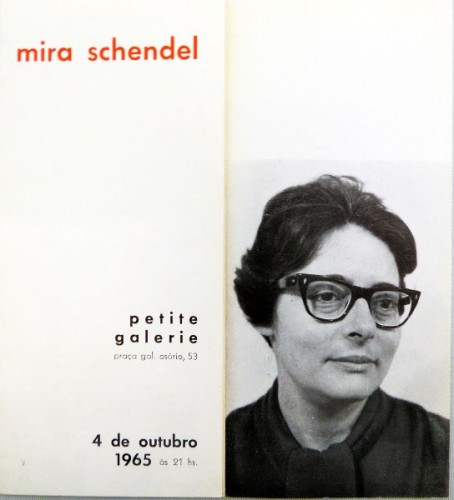

Mira Schendel at Tate Modern

Retrospective of Brazilian Modernist

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 20, 2013

Through several major exhibitions, Century City at Tate Modern (2001), Brazil Body and Soul at the Guggenheim Museum (2001), documeta X organized by Catherine David (1997), and Global Conceptualism organized by Jane Farver for the Queens Museum (1999) we first became aware of Brazilian modernism particularly the work of Lygia Clark, Helio Oiticica, Sergio Camargo and Lygia Pape.

Tate Modern, through January 19, has organized a major retrospective for the Brazilian artist Mira Schendel.

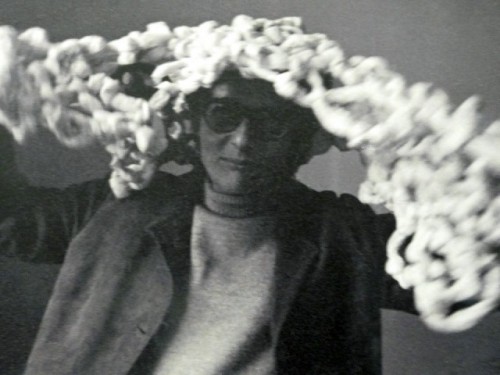

She was born Myrrha Dagmar Dub (Zurich, Switzerland, 1919 - São Paulo, 1988). In the 1930s she moved to Italy and practiced catholicism but as a Jew was forced to cease the study of art. Receiving permission she emigrated to Brazil in 1949.

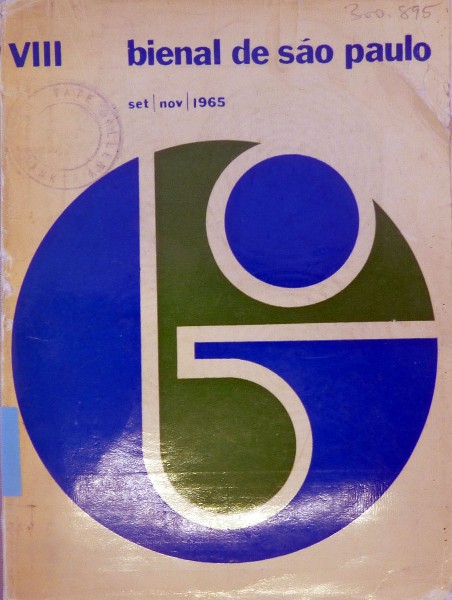

Taking the name Mira Schendel she settled in Porto Alegre, where she worked with graphic design, executed paintings, ceramic sculpture, restored baroque images and wrote poetry. Participation in 1st Bienal Internacional de São Paulo [São Paulo International Bienal] in 1951 brought her international recognition and prompted a move to Sao Paulo. This placed her in the company of restless and eclectic artists.

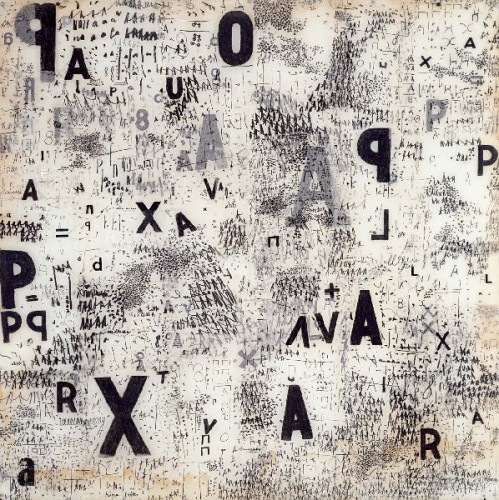

Moving through the fourteen galleries of her Tate exhibition one is struck by the variety, intensity and experimentation of her work. She explored but was never entrenched in any specific movement. Styles ranges from Concretist and Neoconcretist to Lettrism, Color Field painting, minimalism, installation and conceptualism.

There are so many aspects to her oeuvre that it is difficult to get a fix on an artistic persona and dominating motivation. Each new gallery, within an axis of abstraction, is unpredictable based on prior ones. Navigating gallery after gallery it seems that she has been enchanted by a muse to spin another roomful of straw into gold.

We were most grounded early on, after a transitional phase of juvenilia evoking the influence of Morandi’s still life paintings, to minimalist black and white or earth toned, non objective, geometric works. They evoke the American artist Barnett Newman but it is likely that she derived that approach independently.

Working in obscurity and poverty on her kitchen table, initially, she improvised materials or used collage. A breakthrough occurred when a friend gave her a stack of rice paper. This inspired aspects of monotype and different ways of applying ink. The Droguinhas [Trashy Little Things] series was comprised of paper crumpled and shown as such in seemingly random plies or plaited into chains and knots. Some paper pieces were drawn on both sides and shown between suspended sheets of plexiglass allowing recto and verso views.

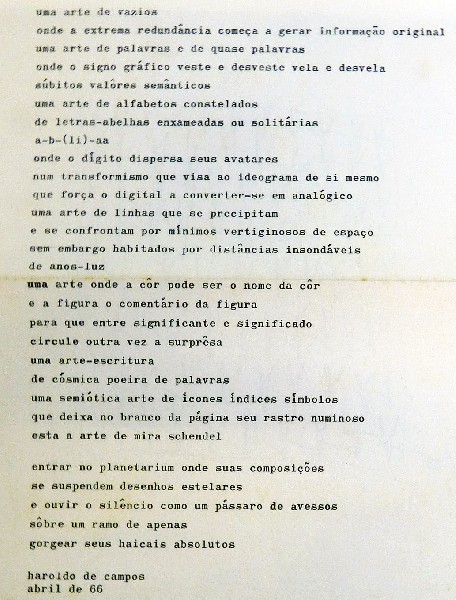

Through philosophy and concrete poetry as well as semiotics she used letters as signifiers and aspects of texts. There is a striking room with large sheets suspended as panels that we weave through.

From 1970 to 1971, she created a set of 150 notebooks. During the 1980s, she produced the black and white temperas, the Sarrafos [Laths] and began a series of paintings with brick dust.

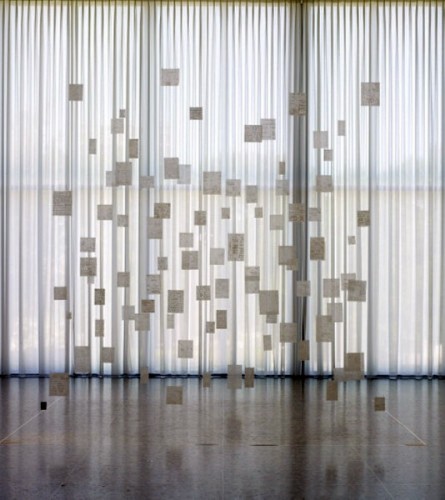

Just when you think you are getting a handle on the artist the next room presents another surprise. The series Trenzinhos [Little trains] comprises rice paper sheets hanging in rows from a clothesline.

While we respect the quality and commitment of her work it seems constrained and boxed in. It is what one expects from a brilliant artist working on the periphery without the support, recognition and patronage that comes from global recognition.

Some critics describe her as the Doyenne of Brazilian modernism. But there is no ready answer for one so famous in her own country and obscure outside of it. Perhaps that conundrum reveals why the work so often feels implosive rather than exuberant, grandly ambitious, and explosive.

It is best to approach this intimate and compelling exhibition by toning down the rhetoric of critical apparatus. We attempted to locate the work within its own confines rather than wedging it into the arc of an international paradigm of modernism.

That said there was yet another discovery.

In 1969, for the 10th Bienal Internacional de São Paulo [São Paulo International Biennial], she exhibited the installation Ondas Paradas de Probabilidade [Still waves of probability]. We entered a gallery of nylon wires attached to a framework that hung from the roof to the ground.

Wow. That came and went from out of the blue.

Especially considering the date it was a remarkable inspiration. There is the inevitable thought of what might have been? It was the kind of breakthrough that cried out for critical and curatorial support. Why did it take until 2013, more than 40 years later, to become aware of such prophetic work?

Perhaps the single answer is that like so many other twists and turns in her practice it was a one off.

The survey ends with a room of black square stick elements projecting from white canvases. They are less interesting than what had come immediately before.

After so many tantalizing glimpses, as aspects of other, larger projects, let us hope that a major museum undertakes to organize an in depth exhibition and history of Brazilian modernism.

What remains unclear are the unique forces that created such an energetic niche of Latin American modernism. Why Brazil? We ask why such interesting work has not yet been accorded deeper recognition and comprehension?

For now this Tate exhibition of Mira Schendel adds a significant chapter to a fascinating, ongoing study.