Santyagraha by Philip Glass

Gandhi Inspired Opera Sung in Sanskrit

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 21, 2011

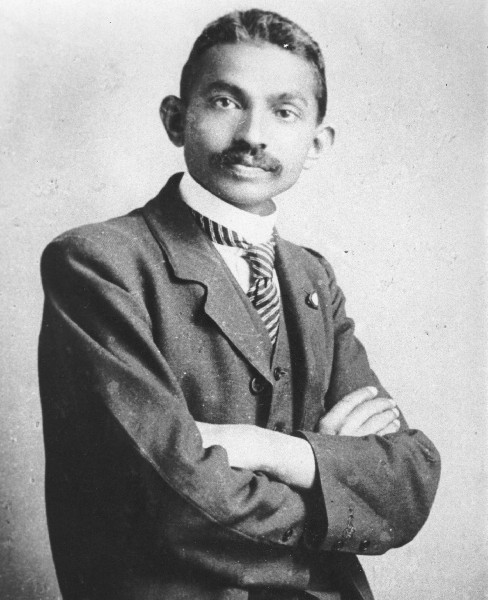

Gandhi was a young lawyer when he received a harsh reception upon arriving in South Africa. He joined the small Indian minority which was discriminated against by the racist white government. Citizens of Indian heritage were required to secure identity cards. These could be randomly demanded by police who also entered homes with no provocation or search warrants.

He was the only Indian lawyer for all of South Africa. Over the next 20 years he developed all of the techniques of non violent resistance that were later used to topple British rule in India. Gandhi arrived in South Africa following three years of studying for the bar in Great Britain. Initially, he wore the attire of a British barrister and submitted to the yoke of colonialism.

As he found his voice and identity he stripped off the trappings of oppression. In solidarity with the poorest of citizens he adapted the dramatic and signifying garb, half naked by Western standards, and the simple lifestyle of the underclass which comprised his primary following.

Philip Glass, arguably our greatest living composer, was inspired by the South African era of Gandhi to compose Satyagraha a riveting, demanding, complex opera in three acts. This past weekend with two intermissions we arrived at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown. Starting at 1 pm and finishing at 5 pm. It was a long and galvanic experience as the Live in HD performance by the Metropolitan Opera pulsated and washed over us.

There are many degrees of difficulty in the music of Glass. The daunting minimalist sharply cadenced phrases of the score were preciely conducted by Dane Anzolini and executed by the superb orchestra. It is astonishing that the musicans can handle the contemporary vocabulary of Glass with the same aplomb as a more traditional classical score. The same must be said of the chorus dealing not only with the difficulties of a Glass composition but added to that learning to sing phoneitcally an unfamiliar dead language. Just imagine the challenge of learning a libretto that you cannot possible comprehend.

Compared to the challenges for the musicians and singers those for the audience are relatively pedestrian.

Unless you are an aficionado it is not uncommon to attend operas not knowing quite what is going on. There is the issue of languages even when there are supertitles to follow along with the text. Even when sung in English, which was the case last year when we attended a broadcast of Nixon in China, it is not always possible to follow the narrative.

By creating a libretto in ancient Sanskrit, based on passages extracted from the The Bhagavad GÄ«tÄ , for which we only occasionally were provided supertitles, there was no possibility of following or comprehending the text.

Apparently Gandhi memorized the 700 mythical and inspirational stories of the ancient epic poem. It was a part of his daily meditation. This was sung compellingly by Richard Croft. Unlike traditional opera there was no correlation between the singing of Croft and actions conveyed on stage.

The aboutness or narrative of the opera was signified by a parallel to what was sung. The pulsing, often staccato musical score was a scrim upon which a narrative, with compelling stagecraft including giant puppets and inventive sets were projected.

There were many wonderful devices used by director Phelim McDermott, designer, Julian Crouch, and costume designer, Kevin Pollard. The strategy was to meld simple materials and images to enhance the abstracted narrative. Gandhi started and wrote regularly for a newspaper. So sheets of newspaper were woven into the action in many inventive variations. The chorus now and then would configure the newspapers to form an ersatz screen on which the single words Tolstoy, Tagore or King were projected defining the theme of the three acts. Characters and puppets enacted dream like scenes from Indian mythology.

Taken as a Gesamtkunstwerk we respond to Satyagraha as more of a metaphor in operatic form than an opera in the manner that we normally understand the medium.

This is, of course, the strength and weakness of the Glass creation.

The intentionally created distance that Glass has evoked, undecipherable language and a disconnect between text and action, knocks the audience off the pedestal of conventional understanding. We are invited instead not to follow the literal story of Gandhi in India but to allow for an entirely new range of associations. We emerge with more of artistic feeling for than historical or biographical understanding of Gandhi. It is the string theory approach of unlocking multiple dimensions rather than following a trajectory with conventional linear perspective. The experience explodes into endless possibilities as the mind and ear are liberated from traditional narrative tropes. Instead we are offered a series of parables and vignettes.

The three acts break down into distinct historical and philosophical phases of his development from conventional, colonialist barrister to ever more radical and inventive leader and liberator. Each act has its mentor.

Act One evokes Count Leo Tolstoy. There was actually a correspondence between them though they never met. The Russian author is a character in a niche above the rear of the curved wall of the backdrop. It narrates how Gandhi, inspired by Tolstoy, has gathered the Indian community on a collective farm. They become independent of apartheid by becoming self sustaining.

The dominant mentoring figure of Act Two is the Indian poet, contemporary and companion of Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore. Here Gandhi and his followers identify ever more deeply with their Indian culture and heritage. In a defining gesture slowly they come forward and toss their ID cards into a pit. Culminating this act of defiance Gandhi sets fire and a ring of flame is seen on stage.

By Act Three Gandhi has evolved as a leader of the resistance. The signifier for this is Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In that niche previously occupied by Tolstoy and Tagore we see the rear of Dr. King before a bank of microphones. His arm is upraised and a finger used to articulate unheard points from iconic speeches.

Much has been said of the great success of the Live in HD broadcasts. Not enough about its frustrations. These were never more annoying than with this production of Glass.

Seeing this as a video production rather than actually being there at the Met was agonizing. It is a work that one needs to see in a theatre to fully comprehend the impact of its intentionality as a Gesamtkunstwerk. In a conventional opera it may make sense for the camera to zoom in during an aria. To see the facial expression that conveys the emotion of the moment. But since Croft was conveying no specific narrative that implies that kind of emotion it proved to be a distraction.

During Act Three there is a compelling action when individuals walk the length of the stage unreeling rolls of broad, transparent tape. Eventually, these form a series of parallel lines which divide Gandhi and his inner circle from the chorus of followers. They begin an agonizingly slow progress across the stage signifying a march of protest. We want to see this full frame showing the entire stage. But the camera frenetically moves in and out seemingly activating and punctuating, accelerating what should be a slow and somber experience. It was just distracting and perhaps a director’s decision that the audience needed to be zapped up a bit rather than lulled into the trance that Glass composed.

The Met often doesn’t seem to understand or trust the creations they broadcast. All that jazzy camera work is a misguided attempt to make opera more broadly accessible.

Upon further reflection I don’t really know whether I can say that I saw Satyagraha. I had an opera like experience which is not at all the opera itself. The attempt at a simulacrum was less than definitive. More ersatz than actual. We were involved in an interpretation, a dumbing down if you will, of a work by Glass and not at all what the composer envisioned.

The good news is that millions all around the world shared in the experience. The bad news is that this was nothing at all like seeing it actually live at the Met. There is a huge difference between that and Live in HD. Let’s conclude that we experienced the Cliff Notes of a magnificent opera by Philip Glass.