San Francisco Symphony's Michael Tilson Thomas

Adams, Prokofiev, Ravel Swoop and Soar

By: Susan Hall - Nov 21, 2014

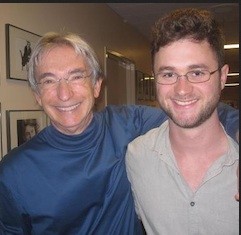

Michael Tilson Thomas with the composer Samuel Adams

The New York Choral Artists were a wonderful wordless sound in the Ravel.

Carnegie Hall suits the San Francisco Symphony and likewise...

San Francisco Orchestra

Conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas

Gil Shaham, Violin

New York Choral Artists

Joseph Flummerfelt, Director

Samuel Adams, Drift and Providence

Sergei Prokofiev, Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 63

Maurice Ravel, Daphnis and Chloe

Carnegie Hall

New York, New York

November 20, 2014

The sound of the evening was unusual and lushly thrilling. It suited the San Francisco Orchestra and Michael Tilson Thomas perfectly. Conventional wisdom places the newest pieces first so people don't exit after warhorses. On reflection, I liked hearing backwards and forward through Adams, Prokofiev and Ravel. Adams grew out of these composers, but what was novel about them in their time stood out having listened to Adams.

All three composers listen to sounds around them and translate them into a musical form. Adams talks about learning 'noise,' which is sometimes defined as "the sound something makes," but at other times more closely related to composition and called "unorganized sound."

Drift and Providence, the second Violin Concerto and Daphnes and Chloe are all organized. But some of the sounds are unusual. In the electronic part of Adams' piece, one critic heard silverware cascading. I heard rattling on an old-fashioned washboard. Adams was in back of the hall, capturing these sounds and then playing them again as the piece proceeded.

Place is also captured. Adams is in San Francisco, the city of wharfs and buoys and water lapping on the shore. Prokofiev had just returned to his native Russia and we hear its folk songs and dances in this Concerto. Ravel, on assignment for Diaghalev and opening his ear to the sounds of Greek myth and the flap of dancers limbs soaring through the air, suggests mythology and great breaths.

Long takes, wide swoops, characterize all three composers. The San Francisco Symphony performs with a seemingly reckless abandon, and yet the music is held together by precision and an incessant beat.

The Second violin concerto was performed by Gil Shaham, an American born, Israeli-trained dynamo. The lyrical passages of the concerto are like those of Romeo and Juliet. Buoyant, gay and lively. Pungent. The piece had originally been given to Robert Soetens, the French violinist, on a year's exclusive and together Prokofiev and Soetens toured Spain, Portugal, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisa.

This concerto marked a turning point in Prokofiev's compositions. He had struggled to write formalist music and now, back in Russia, he returned to the expression of genuine human emotion, choosing the violin, an instrument that sings.

None of the mocking, grotesque effects which had astonished listeners in the development section of the first concerto are present. There are fewer harsh timbres and harmonies. We heard a more restrained and gentle play of tone colors. It is written in a simpler more intimate style. This does not surprise, because Prokofiev had first intended it be in a sonata.

Shaham captured the long, meditative phrases and the romantic outbursts with a picaresque joy. In the third movement, where colorful dance-like motions dominate, Shaham danced too. The complicated technical figurations were executed with biting accents.

Rich polyphony, and imitation in the dialogue between the violin and orchestra were beautiful. Sometimes you could sense Beethoven and Brahms.

The two themes of the first movement were lofty and broad in their melodc lines. The main theme, first performed solo and unaccompanied, is a flowing russian song. Inner variation of the melodic line is accompanied by shifting of strong beats. Snow-covered plains of Russia are evoked and Tchaikovsky and Moussorsky suggested. Tonal shifts and subtle modulations taken by Shaham show it as Provofiev's own.

The second theme is delicate, and sensuous chromatic turns suggest the passionate love themes of Romeo and Juliet.

Shaham made the themes his own. Sometimes lofty and broad. At others full of tonal shifts and modulations interwoven in the bridge section and sustained in a light and playful manner. In the second movement the violin communed with nature, singing over triplets like those in the Moonlight Sonata.

The third movement was rhythmically resilient and stormy. Rich triads of the violin's basic dance theme were sharply emphasized. The fiery motion of this accented, triple-beat dance continued throughout to the finale. Recapitulated, the principal dance theme becomes even more energetic and vigorous.

This has been the year of Firebird, a source of both inspiration and encouragement. Ravel must have noticed that Stravinsky blatantly borrowed the last six bars of his Rapsodie Espagnole in Kastchel's Dance. Suddenly Ravel is brave enough to stand up and be counted.

Dazzling stirring, with infinitely fresh, tender and gentle phrases as one critic said when it was first performed. Strength and sensuality, power and gentleness. Cocteau wrote: "Daphnis is the archtype of those works which belong to no school; one of those works that land in our hearts like a meteroite from a planet whose laws will remain for ever mysterious."

The wordless chorus makes the human voice a part of the orchestra instead of separating it. The New York Choral Artists blended beautifully.

At Carnegie, all three works became what was once called "conspicuously consumable beauty." They were a triumph in the hands of Michael Tilson Thomas who never fails to deliver.