Riccardo Muti Conducts the New York Philharmonic

Thrilling Performances of Liszt, Elgar and Prokovief

By: Susan Hall - Nov 22, 2009

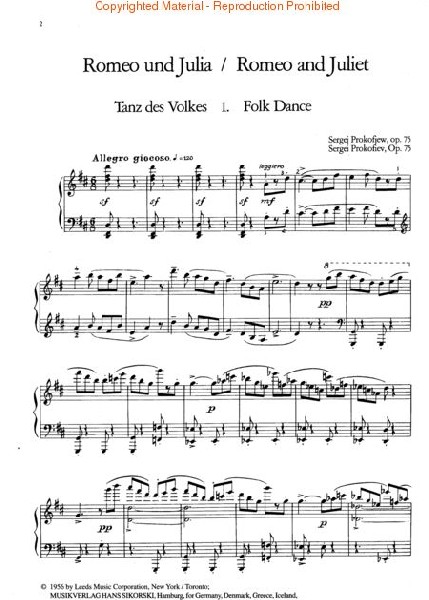

When Riccardo Muti conducts the New York Philharmonic, we are in for an evening of musical bliss. The program on November 19th progressed from Liszt, for whom Richard Wagner had the greatest respect as a composer, to Elgar, whose "Pomp and Circumstance" makes him a household name as students march to receive their diplomas, and finally Prokovief's ravishing "Romeo and Juliet," a grand collection of suites which Prokovief put together when the Kirov cancelled the ballet music they'd commissioned.

Kirov had been killed, many thought under Stalin's order. He was jealous of Kirov's popularity and power. The Bolshoi undertook "Romeo and Juliet" and also put it on hold, arguing that the dancers could not detect melodies. At times the music was so soft they couldn't hear it at all. Prokovief offered to add drums. The composer then cobbled together the "Romeo" music into symphonic suites so they could have a concert life.

Composer and conductor Victoria Bond, in a marvelous pre-concert lecture, showed how each of these composers in his own way, altered repeating themes and opened and retracted the lines of their compositions. The program was entirely comprised of symphonic tone poems, a form which Liszt pioneered. Like opera which combines music and drama, the tone poem can be inspired by an actual poem, the composer's emotional life, or even Shakespeare.

"Les Preludes" was prompted by four poems by Joseph Aurtan depicting Mediterranean scenes, but after revisions, Liszt cited a Lamartine poem as the driving inspiration. Critics savaged him for the change, but others note that the most successful symphonic poems are often loosely connected to their prompts.

Liszt wrote in a preface to the publication of "'Les Preludes," "What is life but a series of Preludes to that unknown hymn, the first solemn note of which is sounded by Death?..." While there are no specific movements, the piece is divided into four sections: Love, war, natural beauty and destiny. It does not surprise to learn that the Nazi's used a triumphant theme played by trombones and trumpets when they announced Nazi battle victories on the radio.

Liszt conducted the premier of "Les Preludes," and is considered a frontrunner of the Weimar school of conducting. In the past, a spirited style had glossed over difficulties. Now focus would be on the conductor's facial expressions and hand motions used to capture the phrasing, dynamics and shape of the composer's intentions. Liszt's rehearsals were considered the finest musical education. However, at one performance of Beethoven's Ninth with Liszt conducting, the orchestra broke down, and Liszt said simply: "Conductors are steersmen not oarsmen."

Maestro Muti must have heard Liszt's plea that future conductors communicate the subtleties of color, tempo, rhythm, accent, balance, contrast and the art of transition. Muti's sweep and precision offer up a brilliant tone immaculately presented. In one unusual conducting gesture, an imaginary tumbleweed successively embraced impels the orchestra forward, at the same time capturing the music. However inadequate any description of Muti's style may be, for listeners there is an unusual passion and lucidity, and both the orchestra and the audience were in the palm of his hand.

We next heard Elgar, in an uncharacteristically Italianate piece. He wrote "In the South" while vacationing on the Italian Riviera while recovering from the death of a close friend. In the Mediterranean town, Alassio, Elgar was delighted to find fisherman drawing their nets in the precise manner that the Roman poet Virgil had described. On an outing to a church at Moglio, Elgar picked up the three-beat phrase 'mo-gli-o' and used the rhythmic triple in the first phrase of "In the South" After the brief, joyful 'moglio' burst, Elgar introduces a strident tone to reflect the Roman invasion and occupation of the area.

Walking in Andora. he found a shepherd and his flock and was reminded of Tennyson's "The Daisy" whose emotions and ideas he wove into the music. A delightful Neapolitan folk song provides the melody of an unexpected solo on the viola. "In the South" expresses a nostalgia for the south even though Elgar glimpsed the landscape through cold winter weather.

Conductors cherry pick the Prokovief suites and Muti began with the magisterial procession music from "Romeo" -- immediately calling forth images of those black-robed figures who would eventually stride across the stage in the ballet version. Melodies successfully skip a half step on the chromatic scale and the tuba plays a minuet. Prokovief is full of surprises that work.

Muti captivates as he draws out not only the dynamic differences, but also the subtleties, which he punctuates with commas, semicolons, dots and dashes -- differentiating pauses in a phrase the way a brilliant Philip Roth sentence does.

To say that Maestro Muti brings out the best in this great orchestra is an understatement. One woman leaving Avery Fisher at the concert's end said, "Now I know why the hall is sold out."

This program will be reprised on Tuesday, November 24th at 7:30 pm. Muti continues his stay at the Philharmonic with performances of Beethoven's "Eroica" on November 27th at 7 pm,. and November 28th at 2 pm and 8 pm.