The New Museum of Fine Arts

Thrilling Art of the Americas

By: David Bonetti - Nov 22, 2010

We’ve been waiting for this for a long time. Sure, there have been signs since Malcolm Rogers became the Museum of Fine Art’s director 16 years ago, as there were a few that pre-dated his arrival here, that something colossal was afoot. Call it change you can believe in. But unlike Obama, Malcolm, as he seems to be universally called, delivered on his promise. (Maybe we need to give the President 16 years as well.) It’s there for all to see in the thrilling new wing for the Art of the Americas, a museum within a museum. It’s so good it might make you fall in love with American art all over again.

When I last covered the arts in Boston, from 1984 to 1989, as the Boston Phoenix’s art critic, the MFA seemed impossible, an immovable dinosaur that, like the Boston ladies who seemed to be its only visitors, had its hats and gloves on and knew what it liked which was, for the most part, not what you were particularly interested in. The Boston art world – artists, collectors, dealers and critics – despaired over the situation. It seemed that the granite mausoleum on Huntington Avenue would never change. There were a few hopeful signs – director Jan Fontein purchased an analytic cubist painting by Picasso; William and Saundra Lane gave their extraordinary collection of paintings by early American modernists; Alan Shestack began to collect African, Oceanic and pre-Columbian art; Kathy Halbreich and Trevor Fairbrother mounted smart contemporary exhibitions and acquired smart contemporary art for the permanent collection – but it never seemed to gather steam, and after every jolt of energy the institution sank back into what seemed to be its natural lethargy. Madame MFA, as I called her, became the biggest whipping boy in town – mixed gender metaphors be damned. Many members of the art community became unbalanced, even hysterical, about the museum: even the good things it did – and there were many – were shrugged off, dismissed. And there are still some today who can’t give it credit for anything. It’s long since time for them to get over it.

During that difficult time – the years that followed Perry Rathbone’s exciting directorship (1955-72) – it seems that many members of the museum’s board of trustees were also dissatisfied with the status quo. Institutions move slowly, but the pace at the MFA seemed glacial. When the lame Shestack administration came to its prolonged end, the trustees acted, naming Rogers, a British curator hitherto unknown in the US, director, giving him a portfolio to turn the museum upside down. He did. Some of his early acts were brutal – remember the orgy of firing he oversaw that was tagged “the Boston Saturday Night Massacre”? And his taste was questionable – Herb Ritts, Yousuf Karsh, Wallace and Grommet – but he turned the giant ocean liner around in, by institutional standards, record time.

I won’t retrace the many steps Rogers took to revitalize the museum starting with the reopening its front entrance, which Shestack had short-sightedly closed for bogus cost-cutting reasons. But all those steps added up to the glorious opening of the new American wing. I’ve spent more than 10 hours in the galleries already, and I feel as if I’m just beginning to get familiar with it.

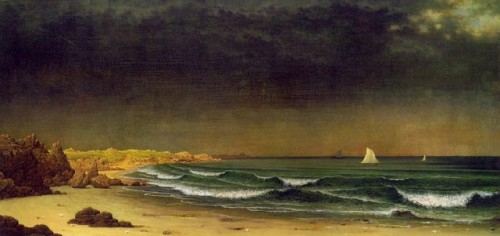

Getting to relearn the great collection of American art the MFA holds, arguably the greatest in existence, with the deepest depths and the broadest reach, with concentrations of important artists like John Singleton Copley, Gilbert Stuart, Martin Johnson Heade, Fitz Henry Lane, John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe, now augmented with work from Latin America, is a life-long project. I look forward to visiting it again and again.

There are galleries here I just love. The Second Level gallery tagged “Salon: American Artists Abroad in the 19th Century” is jaw-dropping in its perfect evocation of a mid-19th century gallery installation. The gallery text notes that if you visited the MFA in its original Copley Square building, you would have seen galleries like this one – pictures hung floor to ceiling, edge to edge, the better works eye-level, “on the line.” To eyes steeped in modernism with the bias that every painting is unique unto itself and deserves the proper space to be contemplated, that sounds like heresy. But it turns out to be fun, exhilarating fun – and appropriate for these pre-modern works. There might be pictures hung so high you can’t really see them as closely as you might like – for instance, Frank Duveneck’s “Circassian Soldier” and John Paul Seliger’s “The Water Seller,” both examples of the 19th century’s fascination with the exotic – but you have to realize that if the gallery wasn’t hung three, or sometimes four, pictures high as it is here, you probably wouldn’t be able to see them at all because they wouldn’t be on view, failing to pass the test for importance. (I’ve never seen either of them hung in the museum during the 40 years I’ve been a regular visitor, although, of course, I could have missed or forgotten them.)

The gallery walls are crimson, and although little of it shows through the dense installation, it makes its intensity felt. The white marble sculptures that fill the space, which ordinarily are dead in the water for me, become here vibrant examples of American neo-classical idealism. I never thought I’d appreciate such sculpture. This installation opens eyes and minds. For this and for the many other highs, hats off to Elliot Bostwick Davis, the chair of the Art of the Americas department, who oversaw the entire installation – all 5,000 works and 6,500 labels.

Another gallery I love, on Level Three, is simply titled “The 1940s and 1950s.” Focusing on both geometric and biomorphic abstraction, it recreates mid-century cool style. They should be piping in Miles Davis and Chet Baker. Most of the work highlighted is what regular museum visitors don’t expect to see at the MFA, even though some of it has been owned by the museum for decades. Almost as densely installed as the 19th century salon a floor below, it still manages to be breezy. Along the perimeter of the space are hung geometric abstractions – paintings by Joseph Albers, Ilya Bolotowsky, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Charmion von Wiegand and Ralph Coburn, a local artist hidden in plain sight only recently recognized by the museum – and more biomorphic examples by Esphyr Slobodkina and the Cuban surrealist Wifredo Lam. The geometric works are augmented by paintings by Joaquin Torres- Garcia, Alfredo Hilto and Helio Oiticica loaned from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros collection of Latin American modernism. It seems that the art world was global, at least that part of it influenced by Piet Mondrian, in the middle of the last century.

Two large display cases that fill the middle of the gallery show the decorative arts of the period. One case, inspired by Charles Eames’s iconic cabinet, is filled with Eames furniture on one side and tableware by Russel Wright, along with other designers, on the other.

The other case is even better. On one side, there’s a vignette of mid-century domesticity with a chair by Vladimir Kagan and a table by Paul Frankl with recently acquired 1940s paintings by Indian Space artists Steve Wheeler and Peter Busa hung above. Cool.

The tightly installed display also includes an early non-kinetic sculpture by George Rickey. Although it was owned by the museum since 1960, I’d never seen it. At last! At least I knew that the museum owned a Rickey. I never knew it owned a model for the gates of Peggy Guggenheim’s Venetian palazzo by Claire Falkenstein and a wire sculpture by surrealist sculptor David Hare, who was closely associated with choreographer Martha Graham. Both works, given to the museum by Guggenheim, inhabit a vitrine that also features a newly acquired Limoges bowl painted by Jackson Pollock and mid-‘50s jewelry by hip Greenwich-Village jeweler Art Smith. This is a brilliant demonstration of how to make disparate objects – some by famous artists, some by those little known – work together in a fresh, unexpected manner.

A third gallery I love – and this was totally unexpected – is devoted to ship models and maritime paintings on the Lower Level. With meticulously crafted models of ships large and small dating back to the early 18th century, and maritime paintings by artists such as Fitz Henry Lane, William Bradford and Robert Salmon, the gallery is one of those “only at the MFA” experiences. It reminds visitors that the wealth of Boston and New England was built on trade and that trade in those early centuries meant ships. That mercantile exchange also led to a curiosity about the larger world that is a regional characteristic that indirectly contributed to the broad range of the museum’s collections.

The “Ship Models and Maritime Arts” gallery suggests, however, a potential problem that could accompany the museum’s new expanded horizons. As you enlarge the collection to include art by Latin American artists and others traditionally not collected by local collectors and the museum, how do you remain true to your own history?

The Latin American art, ranging from ancient Mesoamerican sculpture to contemporary paintings by Claudio Bravo and Cesar Paternosto, offers little challenge to the museum’s identity. From the start the MFA has aspired to be an encyclopedic museum with collections from all times and places – the legacy at least in part of those men who went forth in ships. Pre-Columbian art is the latest area of concentration, following in the path of art from ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, China and Japan. And if the museum collects modern art from New York and Paris, why not from Mexico City and Buenos Aires?

The issue of collecting art not favored by local collectors or by the museum in the past is a more subtle threat, however, to the museum’s identity.

So far I think Davis has maintained a balance between traditional Boston interests and a more national, even global consciousness. The museum showed 20 years ago that it could still show the conservative Boston School artists and other late Impressionists that were at the core of its pre-World War I collection while accepting and celebrating the Lane Collection of New York City modernists, the local school’s aesthetic opposition. Davis’s recent acquisitions of work from the New York-based Aesthetic Movement and the so-called American Renaissance, for instance, does more to enrich the existing collection than to redefine – or undermine - it.

There is no slighting in the new Art of the Americas Wing of the museum’s great collection of American painting, sculpture and decorative arts created locally and patronized by the museum’s early donors. With some 30 works on view, Copley, a self-taught genius and the first great artist to emerge here in the 18th century, is probably better represented than he has ever been. The same, not only with Stuart, Sargent, Homer, Heade and Lane, but also with less celebrated artists strongly associated with Boston like Washington Allston, William Morris Hunt and Boston School painters Edmund Tarbell and Frank Benson. And no one can fault the museum’s displays of colonial furniture, especially the classic works made locally and in Newport, Rhode Island, one of the great centers of colonial furniture manufacture.

But in the race to embrace new areas of collecting and to incorporate a large number of loans, some of them of second-rate quality, the museum has forgotten, I think, some of its strengths. I won’t linger long over the disappointment of not seeing some of my favorite paintings by self-taught artists from the Karolik Collection - particularly the painting by E.L. George of the concerned-looking little girl sitting in a rocker with a basket filled with strawberries nearly the size of her head sitting on the floor beside her – and pictures by Albert Pinkham Ryder, George Caleb Bingham, and the weird John Quidor, among others. Curators have the prerogative to show what they will, and maybe some of these pictures will show up in a later rotation. (Even with all the new space, the museum is showing only some 30 percent of its American collection.)

But it is inexcusable, in my judgment, that not one work by Maurice Prendergast is on view. Prendergast (1858-1924), lived and worked in Boston for most of his life, and he was one of the first committed modernists in American art. (And Boston can boast of few enough of those.) He was championed by Rathbone, and the museum has a number of good works of his in its collection, both paintings and watercolors. This is an omission that should be corrected immediately. A work – or more – of his could be inserted in the American Impressionist or Boston School galleries in place of some of the lesser works currently installed. His omission is a serious historical error in the display of both American art and local collecting patterns and taste.

The fact that Prendergast was overlooked while Tarbell, for instance, is shown almost in excess points toward one of the museum’s consistent failings, which isn’t corrected here – and that is its stubborn reluctance to fully embrace modern art.

If there is one weak point in the current re-presentation of the American collection, it is, despite the gallery devoted to the 1940s and 1950s and an equally exciting gallery devoted to the 1920s and 1930s focused specifically on art deco, the floor devoted to 20th century art. To begin with, it has the smallest floor plan of the four levels, which says a lot about the museum’s priorities.

Cynics might say that that’s fair because the museum doesn’t have a good collection of 20th century art – but that isn’t true in terms of Amercan art from 1900 to 1970, the cut-off date of the Art of the Americas wing. It has an excellent collection of that material – at least through 1950 - one of the best in the country.

But it is not showing its strengths in the current installation, and part of the reason is that there is not enough space to show its modern collection thoroughly. (The same can also be said of the museum’s pathetic gallery devoted to modern European art, but that’s another story.)

The most disappointing Third Level gallery is the one that should be its most deeply satisfying – the one devoted to the Lane Collection. O’Keeffe and Dove are shown adequately here and in nearby spaces, but the richness of the collection, which totally transformed the museum when it was given in 1990, is barely hinted at. Although there is a fine Marsden Hartley on loan, not one of the four Hartleys given by the Lanes is on view. Hartley’s “The Great Good Man,” a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, and his “Painting No. 2,” an abstraction based on American Indian motifs, are especially missed because of the heavy inclusion of American Presidential portraits by artists of an earlier era, in the one case, and the museum’s renewed interest in Native American art, on the other. If there’s no room for them here, maybe they could be shown out of chronology with Gilbert Stuart’s presidential portraits and in the gallery devoted to Native American art.

The museum owns nine paintings by Stuart Davis, one of the most important artists between the Ash Can school and Pop art, seven from the Lane collection, but only two are shown. Other works given by the Lanes by Charles Demuth – his wonderful symbolic portrait of Eugene O’Neill, which would look great in the gallery devoted to the 1920s and 1930s – Ralston Crawford, Niles Spencer, Max Weber, George L.K. Morris, Jacob Lawrence, Hans Hofmann and Franz Kline are nowhere to be seen. And I think that there should be more works on view by Charles Sheeler.

In addition, other works from the first half of the 20th century missing include fine works by John Marin, Lyonel Feininger, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Boston Expressionist Jack Levine, Romare Bearden and Lois Mailou Jones. The absence of the latter two, as well as that of Lawrence, is puzzling because the museum is making a push to collect and show more African American art. (The galleries include two recent acquisitions of mid-20th century paintings by the African American artists Norman Lewis and Al Loving.)

One could go on: the museum’s one area of strength in post-war painting is so-called color field painting, and only a single Morris Louis represents it. (Of course, more of this work could be shown in the museum’s wing devoted to contemporary art, which opens in September.)

Don’t let my final remarks detract from the general impression I wish to convey: the New MFA has dusted off the cobwebs that have adhered to it for decades. It is an exciting place that offers visitors an abundance of aesthetic riches. Few museums are ever fully formed - they change, sometimes abruptly, over time. The MFA is always a work in progress. I just wish that with its fantastic new wing for the Art of the Americas, it had gotten its act together on American art of the 20th century.