Frank Martin's Love Potion at Boston Lyric Opera

Rarity Was Intended

By: David Bonetti - Nov 22, 2014

“The Love Potion” (Le Vin Herbé)

Music by Frank Martin

Based on the novel “Le Roman de Tristan et Iseut” by Joseph Bédier

First performance, in concert form, Zurich, Switzerland, 1942

Sung in English in a new translation by Hugh MacDonald

First performance, Boston Lyric Opera

Boston Lyric Opera

Temple Ohabei Shalom, Brookline, Massachusetts

Nov. 19, 20, 22, 23

Conductor: David Angus

Stage director: David Schweizer

Set designer: James Noone

Costume designer; Nancy Leary

Lighting designer: Robert Wierzel

Cast: Jon Jurgens (Tristan); Chelsea Basler (Isolt, the Fair); Brangain (Michelle Trainor); David McFerrin (King Mark); Heather Gallagher (Isolt’s Mother); David Cushing (Duke Hoël); Omar Najmi (Kahedin); Rachel Hauge (Isolt of the White Hands)

Chamber ensemble from the Boston Lyric Opera Orchestra

Boston Lyric Opera’s “The Love Potion,” was a hit – at least with me - and, no, it’s not by someone named Verdi or Puccini. The author of the work is the obscure but respected Swiss composer Frank Martin (1890-1974), who didn’t compose it as an opera at all. Although it was staged as early as 1948, it’s been called a “secular oratorio,” and the chorus-based work has more in common with oratorios by Handel and passions by Bach than those fore-mentioned Italians. Not to mention Richard Wagner, who, of course, based his greatest operatic creation, “Tristan und Isolde,” on the same story from ancient Celtic myth Martin did. Indeed, working on the eve of World War II, and seeing his work premiered in neutral Switzerland during the war that tore Europe apart, Martin, like so many composers of the era, wanted to compose a work that rejected what he thought was Wagner’s baleful influence. By going back to first sources and stripping his work of Wagner’s overwrought romanticism, he succeeded.

Not that a dutiful concert version of the work would guarantee a surefire hit. Much success goes to the BLO for bringing the work to full dramatic realization. Part of its annual Annex series, in which the company travels to theaters and other spaces not ordinarily used for opera, it was performed in Brookline’s Temple Obadei Shalom (lovers of peace), a handsome space with a low central dome based on the Hagia Sophia. (Incidentally, it was designed by Clarence Blackall, Boston’s great architect of theaters – the Wilbur, the Colonial, the Wang Center, among others.)

The production, directed by David Schweizer, who was also responsible for “The Emperor of Atlantis,” one of the BLO’s few unequivocal successes, rooted the production in ritual. Schweizer, working in close rapport with set designer James Noone, costume designer Nancy Leary and lighting designer Robert Wierzel, created a non-Wagner version of a total artwork.

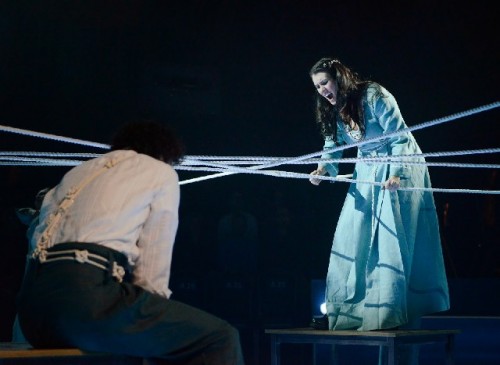

The synagogue’s pews were removed and a circular stage was centered under the tawny yellow dome with a Star of David at its center. Rows of bleacher-like seats surrounded the stage. At its center was a pile of crystal-like stones that glowed with a mystical light, sending a double pillar of light upward to meet the dome. The performers entered wearing hooded robes of white, roughly woven cloth, tied with ropes in Celtic knots. The twelve singers functioned as the chorus, circling the central stage, gesturing in unison, their movements choreographed in a highly stylized manner. As was common in Medieval and Renaissance dramatic music, the principals emerged out of the chorus, returning to it once their solo was done. Almost immediately, one was drawn into the spell cast by the creative team and performers working in concert.

Martin created a true rarity, a Medieval love story/morality play in uncompromised modern terms. The small orchestra of eight members, strings plus a piano, sat on the altar, above the action and removed from it, underlining the separation between the singing and the orchestral accompaniment. Led with sensitivity by David Angus, it took a secondary role in the drama, supplying support for the singers and an occasional prelude or interlude in a musical language that was informed by both the dreamy lushness of Debussy and the structural rigor of the Second Viennese School.

The story, the myth of the doomed love between Tristan, nephew of King Mark of Cornwall, and the Irish princess Isolt the Fair, is familiar from Wagner’s masterpiece, but the plot Martin chose to set is different in subtle ways. The love potion Tristan and Isolt drink, thinking it wine, inflames their love whereas in Wagner’s version their love predated drinking the potion, which only made it impossible for them to deny. Why their love is tragic is the same in both adaptations: Tristan is bringing Isolt the Fair to his uncle King Mark to be his bride, uniting two Celtic kingdoms. Falling in love with his uncle’s betrothed leads to disaster.

The Martin adaptation runs for only one hour and forty-five minutes – the BLO wisely did it without intermission – as compared with the Wagner, which runs nearly four hours (not including intermissions). Still, Martin added characters and subplots including a second Isolt, this one called “of the White Hands” (the name is spelled Iseut or Yseut in Medieval French, Isolde in the Wagner and Isolt in the Martin), whom he reluctantly marries when he thinks the Isolt he loves has abandoned him. In the end, in both versions, both Tristan and Isolt die. In Wagner, from drinking a death potion, but in Martin, Tristan has been wounded by a poison lance, and he dies without realizing that Isolt the Fair has returned to be by his side. When she arrives, she dies beside him, and when they are buried, a bramble grows from his tomb and enters hers, uniting them in love for eternity.

The cast of 12, all but two members or veterans of the BLO’s Emerging Artist training program, were all excellent and extremely well-matched vocally. Granted this is music that doesn’t require virtuoso showmanship, sopranos hitting stratospheric notes with the sweetest of tones, filling theaters of 3,000 plus seats. (The temple sat about 400, its normal capacity is 1,200.) But the road to wisdom is matching one’s resources with one’s ambitions. Here, the BLO got it right.

As is typical of an oratorio, much of the text is narrative, sung as recitative or declamation by members of the chorus, but Martin supplied enough dramatic solos, arias if you will, that the work lends itself to staging, and, indeed, it has been staged increasingly in recent years, last year at the Staatsoper im Schiller in Berlin.

You first realize that this is going to be more than a modern version of medieval plainchant, when Isolt’s mother (an impassioned Heather Gallagher) rushes forward to give the love potion, intended for Isolt and King Mark to Brangain (a stentorian Michelle Trainor), Isolt’s maid. Although brief, the exchange is dramatic.

The work is about the tragic love of Tristan and Isolt the Fair – the chorus sings, after they have drunk the fatal love potion that they are “lost in the ocean of their love” - and they have the most and the best music to sing. As Tristan, Jon Jurgens, sang with a tenor that showed dramatic and dynamic range. When he is separated from Isolt the Fair, he sings a powerfully dramatic soliloquy that riveted the attention. When dying from the poison, his voice grows frail. As he gives up the ghost, he sings the phrase, “Isolt, my love” three times like a whisper, each time fainter.

Soprano Chelsea Basler, whom the BLO has been grooming for a major career, assigning her important but secondary roles last season, demonstrated that she is more than ready for her close-up. A beautiful young woman, she was the ideal Isolt, singing her declamatory texts with passionate intensity, and her arias with exquisite tone and dramatic commitment.

The two low male voices were appropriately macho in their affect. As King Mark, baritone David McFerrin looked every inch a Celtic king and sang with declamatory power. BLO regular bass David Cushing sang with a rumbling flexibility few basses possess. In smaller roles, tenor Omar Najmi as Tristan’s friend Kahedrin and mezzo-soprano Rachel Hauge as Isolt of the White Hands (a particularly thankless role) helped make the evening complete. Members of the chorus Mara Bonde, Tania Mandzy Inala, Brad Raymond and David Wadden were all fine.

With the exception of James MacMillan’s “Clemency,” which I found offensive for its political tone-deafness, the BLO’s greatest successes have been in its Annex series. I hope it learns a lesson from that. Building from modest successes can lead over time to larger and more ambitious triumphs. Less is more.