Peabody Essex Museum

19th Century Sculptor Edmonia Lewis

By: PEM - Nov 24, 2025

The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) presents the first major retrospective exhibition of the work of acclaimed 19th-century Black and Indigenous sculptor Edmonia Lewis. 30 sculptures by Lewis from public and private collections across the United States and abroad will be brought together with a number of additional objects in a range of media, giving visitors an opportunity to learn of Lewis’ mastery of marble and her remarkable, storied life. Co-organized by the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia and featuring newly conserved and never before publicly exhibited works, Edmonia Lewis: Said in Stone makes its debut at PEM on February 14 and runs through June 7, 2026.

Born in Greenbush, New York, in 1844, Lewis became the first sculptor of Afro-Caribbean and Anishinaabe descent to achieve widespread international acclaim. Her mother was a member of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, an Anishinaabe nation in present-day Ontario, and was known for her creativity in weaving and embroidery; her father was a free Black man who may have worked as a gentleman’s servant. Orphaned as a child, Lewis was raised by maternal aunts who profoundly inspired her as an artist, teaching her how to work with birch bark and porcupine quills, craft textiles and moccasins and use a range of materials to tell stories.

At age 19, Lewis met the abolitionist Frederick Douglass at Oberlin College in Ohio. He recognized her artistic talent and encouraged her to “seek the East.” She began her artistic career in Boston, which was a hotbed of antislavery activism when she arrived in 1863. Lewis saw residents across the city actively organizing and gathering to discuss race relations in the United States and the unfolding Civil War. Here, Lewis thought, was a place to stake her claim as a Black artist with a powerful point of view. The young artist quickly set up a downtown studio and connected with the city’s most prominent artists and patrons, forming networks of support with social reformers and abolitionists. Her initial artistic successes came from creating small portrait medallions of famous American abolitionists, artworks that were popular during the Civil War.

Lewis traveled to Rome in late 1865 to join the leading American sculptors of her generation. There, she continued her commitment to the antislavery cause with works like Forever Free, the first sculpture by a Black artist in the United States to celebrate emancipation. Alongside a vibrant community of expatriate women artists, she also helped craft a feminist approach to neoclassical sculpture. Her most ambitious sculpture, The Death of Cleopatra, showed the Egyptian queen defiant in the face of bondage, celebrating female self-determination and the artist’s own fierce independence. Her plaster portraits and vivid, naturalistic stone sculptures depict powerful women, social reformers, Native individuals and religious figures. Through these classically inspired sculptures, Lewis elevated contemporary stories of emancipation, Indigenous sovereignty and religious liberty.

“Edmonia Lewis transcended national, racial and gender barriers,” said Jeffrey Richmond-Moll, PEM’s George Putnam Curator of American Art and exhibition co-curator. “Her body of work asserts a unique voice in the history of American art. This retrospective exhibition places Edmonia Lewis and her sculptures within the context of pressing social concerns of her time and ours. Together with Native and Black scholars, artists and community members, we also explore how Lewis reconciled her art and her identity in the face of prejudicial laws, shifting public sentiment and competing conceptions of what it meant to be Black and Indigenous in the 19th century.”

The exhibition underscores themes of community, reform and resilience and looks at the lifelong impact of both Black activism and Indigenous community on her sculpture practice. "Sometimes the times were dark and the outlook was lonesome, but where there is a will, there is a way,” Lewis recalled in 1878. “That is what I tell my people whenever I meet them, that they must not be discouraged, but work ahead until the world is bound to respect them for what they have accomplished.”

The breadth of Lewis’ life’s work, her wide-ranging networks and her long-standing influence also emerge through photographs, decorative objects, Indigenous belongings, literature, 19th- and 20th-century art and contemporary works, including recent acquisitions by the London-based interdisciplinary artist Gisela Torres and Serpent River Ojibwa installation artist Bonnie Devine. In-gallery videos and digital interactives engage Lewis’ story with a variety of audiences, while collaborations with Black and Native scholars and academic partnerships with Salem State University deepen understanding of Lewis’ life and work through shared storytelling, dialogue and collective reflection.

“Lewis’ legacy looms large for Black artists working today,” said Lydia Peabody, a Curator-at-Large at PEM. “Gisela Torres is an American-born, London-based artist who learned that Lewis was buried in a neighborhood cemetery where Torres frequently walked. Beginning in 2018, Torres has created a series of works inspired by Lewis as an artist-ancestor. Looking for Edmonia (Self-Portrait), on view in the exhibition, is her ongoing project of reclamation.”

The Indigenous Artistic Worlds section of the exhibition is anchored by Lewis’ Hiawatha’s Marriage (modeled 1866), inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha. This section underscores Anishinaabe artistic traditions as central to Lewis’ creative development, traces her lifelong negotiation of global networks of trade and exchange and reveals how the Native American imagery in her Longfellow-inspired sculptures challenges 19th-century myths of Indigenous disappearance.

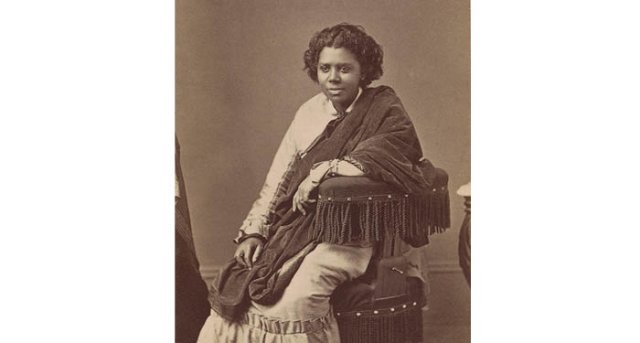

A section called The Studios of Rome explores the materials and techniques for carving marble sculpture that Lewis learned in Italy and employed throughout her career. Through sculptures, historical photographs and design elements crafted in collaboration with Skylight Studios of Woburn, Massachusetts, this gallery helps viewers understand Lewis’ studio as a space of making, self-promotion and cross-cultural exchange. A recently conserved sculpture, Cupid Caught, gives further insight into Lewis’ working methods, in collaboration with objects conservator Amy Jones Abbe and the fabrication expertise of Keystone Memorials of Elberton, Georgia. Portrait photographs of the artists by Henry Rocher and Augustus Marshall, along with periodicals, newspaper criticism, portrait busts and other print materials, examine how Lewis publicly asserted her humanity, individuality and determination as an artist.

The exhibition's final section considers religious and mythological subjects, which resonate with Lewis’ activist spirit, her concern for the marginalized and her belief in art and religion as a means of liberation and renewal. These works also reflect the sculptor’s deep ties to Italian and expatriate Catholics after her baptism into the Roman Catholic Church in 1868, and the ongoing support that Christian religious organizations, Protestant and Catholic alike, offered her in the final decades of her career.

Following her death in London in 1907, Lewis’ legacy endured in Black communities, yet her contribution to American sculpture has largely been underrecognized. Some of her great masterpieces were rediscovered decades later, while others remain lost. Said in Stone features several sculptures by Lewis that have never been exhibited before, along with cutting-edge research that brings to light previously unknown details of her life and career.

“Said in Stone is an ongoing project of recovery and rediscovery. My hope is that this exhibition introduces our visitors to Edmonia Lewis’ art and life within the communities that influenced her and vice versa, and within the wider history of American art,” said Richmond-Moll. “There is something for everyone in Edmonia Lewis’ story. We hope visitors will come to appreciate Lewis’ impressive, lasting legacy as an artist who prevailed against all odds.”