Museum of Fine Arts Pimps its Masterpieces

Fenway Visitors Find a Bare Cupboard of Favorite Works

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 26, 2012

It is normal for museums to lend their masterpieces to other museums. Mostly this entails the quid quo pro process of receiving loans for special exhibitions. Usually this is a straight up trade with curatorial, insurance and handling fees attached. More often, however, recently the primary motive seems to be cash.

When a museum is undergoing extensive renovation, which is currently the case with the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, it is customary to bundle highlights of the collection as a traveling exhibition. In the case of the Clark this has been enormously successful and entailed several years and continents.

It is a marketing and PR bonanza that raises the visibility of the superb museum and its astonishing collection. The grand tour raises money and valuable bargaining chips to negotiate loans when the museum finishes its renovations designed by Tadeo Ando. There will be generous new special exhibition space to display the fruits of this period of sending its treasures on tour.

Some years ago, when the Boston Museum of Fine Arts was renovating its Evans Wing of Paintings, its works by John Singleton Copley were sent to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Later, in exchange, Philadelphia loaned to Boston its many works by Thomas Eakins.

This is the paradigm of doing business in the museum world.

MFA director, Malcolm Rogers, however, has a reputation for entrepreneurship which overreaches boundaries. He has brought to the museum special exhibitions which are more focused on the bottom line of ticket sales than reaching the benchmark of standards for a world class museum.

As the Boston Globe reports more than the usual number of museum’s best loved masterpieces are currently stripped from its walls. While many are legitimate museum swaps, a bundle of 26 works have been loaned, for an undisclosed amount cash, to the Italian for profit organization Linea d’Ombra.

In this case the Italian museums which display the works through Linea d’Ombra have paid a handsome fee with no obligation to loan its masterpieces to the MFA.

This is a shift toward the ever widening direction of viewing collections as liquid assets.

When Brandeis University explored selling off the most valuable works of its Rose Art Museum there was also discussion of having Sotheby’s negotiate loans for cash. The MFA is clearly moving in that direction.

Strict museum rules and ethics mandate that a museum may not deaccession works for operating revenue. Works may be sold or traded only to acquire other works. Occasionally, museums bundle a number of “minor” works to trade up for a coveted masterpiece.

This is an often complex but legitimate practice. But stripping its walls of a large number of works for a fee is a new step in the wrong direction. Of course Rogers, looking at the books, may well justify this as a creative means of paying for rising costs much of it from the expansion of the museum and increased overhead. Having built the new MFA now Rogers must find ways to pay for it.

Not that any of this is new.

Under the watch of former MFA director, Alan Shestack, the museum negotiated for the creation of a branch of the museum in Nagoya, Japan. Their partner was mostly interested in the MFA’s depth in impressionism. While nominally loaning to the MFA Nagoya the newly formed institution had no works to loan back. The contract was described at the time as worth about $1 million a year to the museum. By today’s standards that’s a really good deal.

But there are risks entailed. Curators and conservationists are well aware of the collateral damage, potential wear and tear, of shopping around its treasures. Today, arguably, there are state of the art safeguards in handling the shipping of works of art. Museum curators close the crates at the lending museum and are curriers when they are opened at their destinations. It is a very costly process to travel an exhibition. Reports of loss or damage are relatively rare.

Of course the greatest loss is to the museum's visitors. Imagine touring the Louvre and not seeing "The Mona Lisa." Or the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. only to find that Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party” is not at home.

It’s acceptable if the loan will eventually result in a stunning special exhibition. And quite another matter if the missing masterpiece is out earning the rent. At that point Rogers and his colleagues are less like museum directors and more like pimps.

Excerpts from the Globe’s coverage by Sebastian Smee.

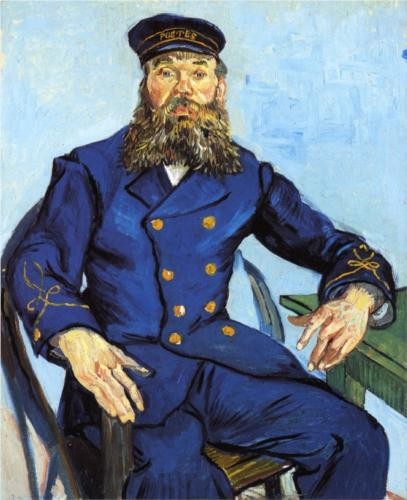

“Visitors to the Museum of Fine Arts this holiday season can see the celebrity and fashion photographs of Mario Testino . But if they wander off into the permanent collection galleries, they won’t find the museum’s most famous Renoir, “Dance at Bougival.” Nor will they see any of the MFA’s five paintings by Cezanne, five of its six great paintings by Edouard Manet, its most distinctive Monet (“La Japonaise: Camille Monet in a Japanese Costume”), or its two greatest Van Goghs (“Postman Joseph Roulin” and “Lullaby: Madame Augustine Roulin Rocking a Cradle [La Berceuse]”).

“Some of these works have been lent to serious and scholarly museum shows in the United States, Japan, and Europe. Agreeing to such loans is common practice, and builds goodwill for when the museum asks to borrow for its own exhibitions.

“However, the MFA, eager to raise revenues, is also renting out many of its most prized works of European and American art to for-profit enterprises. A total of 26 paintings, including the marquee “Dance at Bougival” and “Madame Roulin,” have been sent to exhibitions in Italy organized by a private company called Linea d’Ombra, for a large, undisclosed fee.

“The combined loans and rentals have resulted in what Malcolm Rogers, the MFA’s director, readily admits is a “traffic jam” of missing masterpieces. “We admit there is some crowding [on the list of masterpieces sent away],” Rogers said in an interview with the Globe. “Everything has come together at once.”

“In the meantime, visitors to the MFA can be dismayed to find its most famous paintings missing. Other absent masterpieces include Velazquez’s “Luis de Gongora,” two of the MFA’s three great El Grecos, two of its Courbets, its only major painting by Edvard Munch, and arguably its greatest Degas, “

" ‘As an art history professor, it seems perfectly reasonable to expect that certain canonical masterpieces are on display in the museum,’ said Jonathan Unglaub of Brandeis University.

“The Italian shows currently showing works from the MFA, in the cities of Vicenza and Verona, are titled “Raphael to Picasso” and “From Botticelli to Matisse.”

"Linea d’Ombra is run by art historian-turned-entrepreneur Marco Goldin, an impresario who has been dubbed the “King Midas of the art world” by newspapers in Italy. During the past decade, Goldin has found success persuading northern Italian cities to pay steep fees to mount popular exhibitions of borrowed artworks. Goldin promises that these exhibitions will boost local economies and do wonders for the host city’s image. “Raphael to Picasso” attracted 100,000 in its first 47 days.”