David Wilson Five

Avatar Aftermath Then to Now

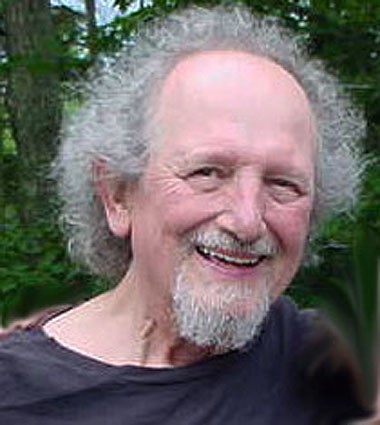

By: David Wilson and Charles Giuliano - Nov 27, 2010

Charles Giuliano When you decided not to continue publishing Avatar at the end of the summer of 1968 I needed a job, It was possible then to survive on cheap rent and brown rice. Our friend Jim Silin was very helpful and made many a meal as we sat around the TV in his living room. He later left Fort Hill to settle as a farmer in Maine. He was into the blues and was an influence on me. For a time we performed as The Total Gonzo Band. I was the drummer and his wife Kathy (Spencer) was the singer. Her big number was “Love Potion Number Nine.” We played a couple of gigs with the mike taped to a broom, taped to a bar stool.

In the absence of Ed Jordan I had designed the Avatar covers and even did a hand color separation for the Fourth of July issue. I took those issues and applied for the job as art director for Boston After Dark (later the Boston Phoenix). I was hired but in way over my head. My assistant Linda knew more than I did and, quite rightly, she replaced me.

But I stayed on as the art critic with a weekly column Art Bag. The editor was a Brandeis colleague, Arnie Riesman. He was really supportive. My pay was $50 a week and I managed to live on that. By then Arden and I split up and I moved in with Silin.

Later, in 1969, Tim Krause, who I had grown up with in Annisquam, left the Herald Traveler as its rock critic, to take a gig at Rolling Stone. Tim wrote “Boys on the Bus” and his sister, Lindsey, is an actress who was married to David Mamet. He recommended me and I got the job at the Herald. I became an established journalist with a daily paper. That lasted until 1971 when the Herald lost its TV station and was sold to the Record American. Other than a few star reporters and editors the entire staff was laid off. It was a sad day in the news room.

While at the Herald I got to hang out with musicians like Elton John and Miles Davis. I spent a lot of time with Captain Beefheart who asked me to join his band. Everything I know I learned from talking with musicians. Although I had no formal training, I had a good ear, and had been a jazz fan since high school.

I got to cover the Newport Jazz Festival and scooped when it was trashed on the front page of the Herald. My pal, Ernie Santosuosso, The Fox, ran a review of the concert which never happened in the Globe. He filed early and wanted to blow a head on the lead before midnight. He never got to do that because, when the riot broke, I was in the phone booth to the front desk feeding live notes and quotes. There were two phone booths in the press tent. The minute it happened I dragged the Herald photographer, Jimmy Carlson, out of the photo pit. He didn’t want to come. But I screamed at him and he got shots of kids breaking down the fence and then raced back to the paper. Later, he thanked me for the bailout.

During six months of unemployment benefits I read deeply into WWII and hung out at the Patisserie. By then, I had moved to Cambridge with a cave in the basement of University Road. It was the notorious Murder Building; so named for a couple of spectacular crimes including one by the Boston Strangler. The other, never solved, entailed a ritual murder of a young anthropologist who had worked in the Amazon.

Peter Wolf and other underground luminaries, like Warhol, hanger on, Ed Hood, musician, Nancy Michaels, and WBCN DJ, Jim Perry, were neighbors. That huge basement apartment was where I held a famous party for Alice Cooper. It was catered by Warner Brothers. Loudon Wainwright tried to strangle his wife on my kitchen floor. I had a piano in the kitchen and there was a lively jam session. Everyone was there including the J Geils Band, The Modern Lovers, and the Sidewinders (Andy Paley), all of the WBCN DJs, to mention just a few. By morning, the place was trashed and staggered in to work. My editor at the Herald wouldn’t let me cover the show because he thought Alice Cooper was a drag queen. The next evening Maxanne, a ‘BCN DJ, came by just to take in the aftermath. Decades later I still run into people who say they were at that party.

After the Herald, I wrote for a bunch of weekly and music papers like What's New, The Paper (Newburyport), The Boston Ledger, the daily Patriot Ledger, Art New England, and Art News. For a streak I was working at Sandy's club in Beverly. We had a lot of great jazz artists and I got him into booking blues guys from Chicago.

Eventually, I went back to graduate school at Boston University to study art history and ended up as an academic. I am now retired from Suffolk University.

Can you fill us in on what happened for you after Broadside ceased to publish? In what way did you stay connected to music? During the past year we have gotten back in contact and you have been writing music reviews for us. How does it feel to be back on the scene?

David Wilson Back in 1961, before I started Broadside, I met Harry Oster when he gave a presentation to the Folk Song Society. Harry was originally from Cambridge and a professor at a University in Louisiana. He had done a fair amount of field collecting and produced a number of exceptional records on his Folk-Lyric label. Joe Boyd, a Harvard student and blues devotee, and I, proposed to Harry that we become distributors for his label in New England. When Harry accepted, Joe and I formed Riverboat Records and set out to acquire other little-known folk labels to represent. (Like Arhoolie and Yazoo) When I started publishing Broadside I gave up my half of Riverboat to Joe.

On graduating from Harvard, Joe sold Riverboat to another group of Harvard students, and he went off to the UK. There he enjoyed a glorious career producing Pink Floyd and numerous other legendary musical entities.

Riverboat was eventually sold again, sometime in early to mid ‘60s, to Ralph Dopmeyer. Ralph was one of those Cambridge eccentrics of whom there are a multitude of stories. He had a degree in Naval Architecture from MIT, was an expert cabinet maker, and an enthusiastic sailor. I first met him when he dropped by Broadside to give us a review copy of his first LP on the Riverboat label. It was John Fahey’s “Death and Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death.” Over the next year or two Ralph often dropped by the offices to provide us with review copies of new releases, to use our typewriters, or just swap stories.

Ralph knew that I had been involved with founding Riverboat. When he had the opportunity to sail a boat to Europe for refitting, and back again, he asked Sandi Mandeville and I if we would be willing to manage Riverboat while he was away. We worked out an arrangement, and moved his inventory into our offices.

I think it was at the Newport Folk Festival, in 1965, that I met John Sdoucos. He was running the press section and the credentials office. He proposed that, after the festival, I come and talk about working out of his Boston office. At that time he and Fred Taylor, who now manages the jazz club, Scullers, were partners. Aesthetic differences led to them parting shortly after I got involved.

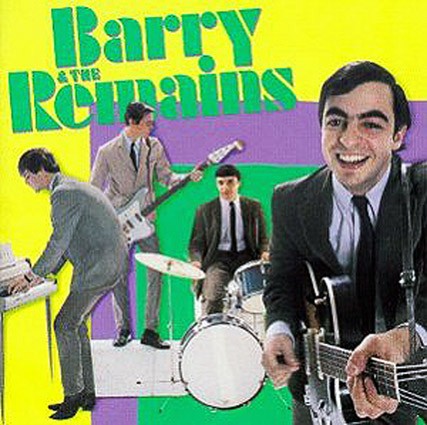

John set up a booking and management agency called Music Productions, managing a local Boston group called Barry and the Remains. He and his wife, Leah, I and Don Law worked out of the Boylston office just over Pall’s Mall. Primarily, we booked major recording talent into college concerts. It was just turning into big business in those days. John and Leah took me under wing and I often had dinner at their apartment with them and often some transient musician or other. I remember sitting down one night to find Diana Ross across the table from me.

I helped develop the Music Productions logo, wrote publicity releases, consulted on folk talent for college bookings, and generated Remains publicity materials. We were involved with a summer series of concerts at the Public Gardens during a couple of summers and I did some live remote broadcasts over WTBS-FM one summer. As part of their organization, I got to work with the press section of the Newport Folk and Jazz Festivals for the next couple of years. At the same time as all this I was managing The Odyssey coffeehouse and publishing Broadside, writing for WGBH-TV, and running Riverboat Records. Don’t ask me how. I could not do one tenth of it today, let alone figure out how I was doing it then.

CG I remember John well. We worked closely together when he produced the summer series of Concerts on the Common. I reviewed those shows for the Herald and got to hang out with bands like the Allman Brothers, Jessie Colin Young, and Rod Stewart. I interviewed Richie Havens who John was managing at the time. Of course, Freddy Taylor was a friend when I covered Jazz Workshop and Paul’s Mall. A couple of years ago we reconnected when he founded the Tanglewood Jazz Festival. He did a great job but was nudged out by the BSO. I also was close to Ted Kurland who booked college gigs for jazz artists. Sometimes I was the MC for his shows like Keith Jarrett at Harvard’s Sanders Theatre. Ted managed some great artists especially the Boston based, Gary Burton, and Pat Metheny. Through Ted I got to hang out with Ornette Coleman and even Phillip Glass and Steve Reich.

DW At the turn of the decade, as the alternative press was in turmoil, the technology that permitted videotaping to become generally available was suddenly attractive. Sandi and I along with Broadside reviewer, Tom Murray and Bill Desmond, Bob Wiener and Larry O’Connell started collaborating. Between ‘69 and ’70 we produced 3 issues of what was intended to be a publication in video. We titled it The Broadside Free Video Press and dubbed it onto 20 minute reels of ¾ inch computer tape bought at surplus government auctions and cut to length.

I had been a psych major back at BU during the late ‘50s, but never felt comfortable with the clinical approach. A course in Psychodrama exploring role playing techniques developed by Moreno. That seemed much more promising to me. In the latter half of the ‘60s it translated into an interest in the developing field of Humanistic Psychology. I got involved with the concepts of encounter groups and the ideas of psychologists like Erich Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Fritz Perls and Eric Berne. The only encounter groups I could find were far too expensive for me or any other “street person” as we thought of ourselves.

In the fashion typical of the time I started to run ads in Avatar and Broadside announcing meetings for people interested to get together and form free, independently functioning groups. The Charles Street Meeting House provided us with free space to meet. I arranged with some members of the OD department at BU to structure the meetings and facilitate groups. They were forming with the promise that they would be recommended to any group that decided they wanted professional leadership.Over the two nights of meetings from over a hundred attendees about a dozen groups were formed.

I had joined one on each night and knew people in several others. The two I was party to stayed together over a year. Others I am sure were not so fortunate. I noted years later that the idea of self -forming groups was still active and that the classifieds often ran ads looking for members.

I too had met Arnie Riesman, as he & I were part of the creative team for “What’s Happening Mr. Silver” which was being produced at WGBH. I think he is still doing a quiz show on WGBH-FM and, last I heard. was vice president of the American Civil Liberties Union for Massachusetts. At the close of 1969, I consulted with WGBH again on a segment for the PBS New Year’s Eve show “Artists Look At the ‘60s.” We did the music segment that looked at the ‘60s through the music of the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and the emergence of the Blues with a commentary by Taj Mahal.

I thought I had a steady gig when the FM manager hired me to do a weekly show which would feature live music and interviews with musicians. He hired me at 5:30 PM on a Friday afternoon and was fired at 6:00 PM. The new manager, if he even knew I had been hired, declined to honor the agreement.

Sandi Mandeville married and moved off to California. Our video venture with Broadside metamorphosed into an expanded operation with a dozen projects all too far ahead of their time. Most of them are now run of the mill and taken for granted. On speculation we ran a CCTV project in the Sheraton Boston, and a Video coffeehouse, The Video Frontier, on Boylston Street. I had married, was living in Brookline and still running Riverboat records. It was slowly being raided manipulated and deconstructed by the bigger corporations. For awhile I had been writing music reviews for you at the Herald-Traveler, and then we collaborated as publicity agents, as WAG (Wilson and Giuliano), alternating weekly press releases and commentary. When that petered out you started the fanzine Staple.

I did some writing as well for the East West Journal with some new-age musical perspectives

In 1972 and ’73 I had a small Rockefeller Grant to develop some video art. It was great fun, an important learning period for me, but my ideas were still too far ahead of the technology to be practical. Today would be just right but whether I would have the energy or not is questionable.

I finally gave up on my first marriage, at the end of 1973, and ended up living in the Broadside offices. Those were hard times though, in a strange way, they were also very happy. I was still involved with several diverse projects. I took a job as night desk clerk at the Cambridge YWCA working an 11 PM to 7 AM shift. I would come home, sleep ‘til noon, get up and work on Riverboat chores, then go back to bed from 6 PM to 10 PM, get up, and go back to the Y.

Off and on during that time, I started working with Kate Frank, recording real time classroom interactions between children with and without physical disabilities. A small grant allowed us to shoot, edit and produce a series of tapes with portable video recording equipment. Kate used the tapes to build a curriculum with which to teach professionals in the field how to assess strengths and weaknesses of the disabled under their charge. We were very proud of what we had done with the budget we had. Kate used the tapes successfully in a number of workshops, but they did not, and by the very nature of what we were trying to do, could not, meet the standard of production values for the educational materials industry. We finally gave up on the project.

On a whim, I took a course at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education on Role Play. The Instructor was a former IBM Human Resources exec who, as it turned out, had also been a participant in the encounter group meetings we had organized at the Charles Street Meetinghouse. I enjoyed the class immensely and jumped at the opportunity when Bob Eagen invited me to co-teach it with him the following semester. During that summer of 74, Bob left me to teach it on my own, giving me half the stipend CCAE paid him.

I loved it and ached to do more. The night that class ended, there were conga lines weaving through Harvard Square, celebrating the announced resignation of Richard Nixon. It was truly the end of an era.

Later Bob handed his course over to me and from ’77, through the first half of this decade, I became a fixture at CCAE. I remember you were teaching there too for awhile. I built a catalogue of personal growth courses. When I got involved with computers in the early ‘80’s I started teaching word processing. I made a gradual transition from one to the other. They were not really that different in my experience. In between, I contributed to a computer book, wrote a manual on spreadsheets, wrote for, and edited, a couple of newsletters.

In between I managed a Tee Shirt store at the eastern edge of the Square and was a partner in a word processing studio.

By the mid’70s I was pretty jaded with the music industry. Most of the folk, rock and pop music that came my way seemed not only derivative, but derivative of derivative. Partly that came from listening to a dozen or more new albums every day. The major factor, however, was that the recording industry had transitioned from recording artists to recording sound-a-likes. The profit motive trumped the aesthetic motive. It’s not hard to see how that as a natural evolution; even if it obviates the reason for existing in the first place.

I retreated to listening to old favorites, some jazz, Indian Ragas which always seemed fresh to me, and early Baroque.

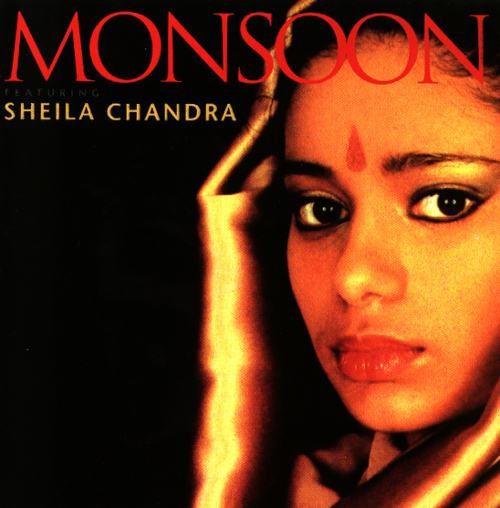

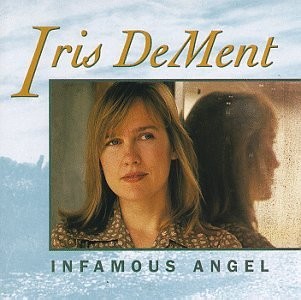

I did come across some exciting folk and roots type musicians every once in a while, Sheila Chandra, Iris Dement to mention two. But it was not until last fall and reconnecting with you, coupled with a desire to commemorate the life of our mutual friend, David Omar White, that I considered writing again. Before I knew it I was tempted to parade my ignorance in public again and here we are.