Dudamel Conducts LA Philharmonic

Roberto Bolle and ABT Dancers Add to Musical Thrills

By: Susan Hall - Nov 28, 2015

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Gustavo Dudamel, conductor

Britten: Young Apollo

Stravinsky: Apollo (choreography by George Balanchine)

Roberto Bolle, Apollo

Hee Seo, Terpsichore

Stella Abrera, Calliope

Devon Teuscher, Polyhymnia

Shostakovich: Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47

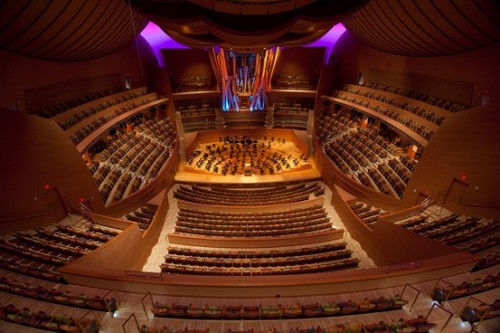

Walt Disney Hall

Los Angeles, California

November 27, 2015

Gustavo Dudamel is a phenomenon in music. He more than deserves the enthusiasm with which he's received.

Ever measured, even as he strides onto the stage, he seems to glide. No artistic statements in loose black shirt and sneakers. He wears tux and tails, with a stiff starched collar, the mop of hair on his head now trimmed. He has a charm about him: impish and obviously full of fun, as serious as he is about his music, in whose honor the muse Polyhymnia danced.

Dudamel conveys the child’s delight we associate with Mozart and a master’s command of music. His programming choices breed memories for stalwarts in the audience and whet a new audience’s desire for innovation.

His special touch was the inclusion of what is often thought to be minor Britten, a short piece honoring the Apollo of Keats’ poem Hyperion. Joanna Pearce Martin performed on the piano as Britten himself had at the premier. Her ascending scales splashed and then cascaded.

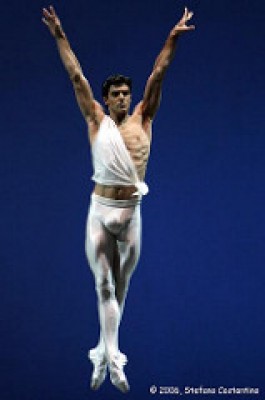

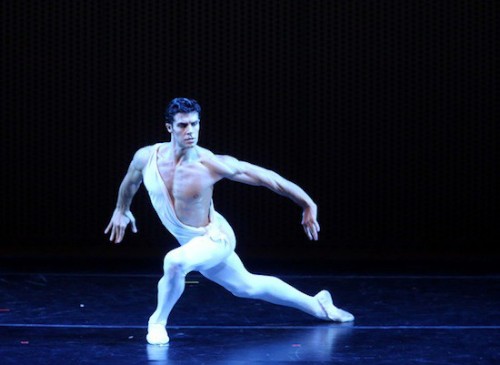

Then Dudamel plunged into Stravinsky's Young Apollo, written on a commission from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, founder of Tanglewood. Dudamel imported principal dancers from the American Ballet Theatre, featuring its exciting Italian dancer Roberto Bolle. Keats’ terrible right arm dances as Bolle points the way to Parnassus.

The program concluded with Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony, which Dudamel took from an almost inaudible back wall of a cavern, hidden in darkness and silence, to a smashing conclusion with five percussionists joining the trombones, trumpets, tuba and horns in full force.

When Frank Gehry was commissioned to design Walt Disney Hall, he made one firm condition: that the acoustical firm of Yasuhita Toyota in Japan be hired to work ear-to-ear with him on the design so that the Hall would have the best possible acoustics. The Fisher Center at Bard, which Gehry also designed, has these astounding Toyota surround-sound acoustics. So too Helzberg Hall in Kansas City, which Moshe Safdie designed.

The warm blond Douglas-fir wood walls are familiar in Gehry’s work. The stage is set down, with viewers on all four sides. A square in the round. Actually one side rises from the orchestra seats up to a third tier. It faces a smaller section which sits on either side of a monstrous organ which looks directly at the conductor. The other two sides are caught in an abbreviated semi-circle. There are four openings in the blond wood arching over the ceiling, and through them peers a royal blue roof in this the most democratic of Halls, where the audience and orchestra start on the same level.

The stage itself is adaptable. The orchestra was small for the Britten and Stravinsky and in back of them, an actual stage arose, which served as a platform for the dancers. Because there appeared to be no exit from the stage, except the steps on which the dancers arrived, Apollo was tucked into a wall watching when the Muses dance. Apollo would have done just that on the way to Parnassus.

The muses dancing here are Terpsichore whose name means delight in dancing; Polyhymnia, the muse of sacred music and dance, and Calliope, the muse of beautiful voices. Everything happening under the conductor's baton was celebrated.

The choreography was Balanchine’s and matched the classical Stravinsky. The excitement came from the taut, sprung dances. Entwined with Apollo, the three women did not compete, but held up the Sun God with music and their dancing.

Bolle is sinuous and glamorous, a perfect figure for the daring God who shuffled off his mortal coil for the pantheon of Olympus. Hee Seo , Devon Teuscher and Stella Abrera set him off and up as they invited with their muse-like steps.

In an age when orchestra’s seek to satisfy with more than one form, this Stravinsky was enticing for the ear and eye.

At first you ask: how does Shostakovich fit? Like Britten’s celebration of Apollo and the unleashing of Stravinsky, Shostakovich wrote this symphony to please. He succeeded, but also by implanting impish digs at dictatorship.

In the 5th Symphony, Dudamel was able to display individual members of his troop. Flutist Catherine Ransom Karoly was the principal soloist. The intense clarity she brought to the melodies was transforming.

The piercing piccolo of Sarah Jackson was counterbalanced by Michele Zukovsky on the clarinet, a wonder. Andrew Bain played a penetrating, lyric melody on his horn, to say nothing of the percussionists, mounted on high, all five of them, giving it to Stalin.

It is easy to imagine Dudamel next door at The Broad museum, wandering through Abba’s The Visitors as filmed by Ragnar Kjatansson. Will future audiences be encouraged to sit nude in their bathtubs nodding their heads to Mozart? If setting and visuals are important for today’s audience, we may not be far from tub-listening to videos broadcast from Disney Hall. If anyone can make this future work it is the passionate and adventuresome Dudamel.