Powered By Free Design

UK Pylon Competition Sought New Design

By: Mark Favermann - Nov 29, 2011

Bystrup, a Danish architecture and engineering firm, recently won first prize for a new design for United Kingdom electricity pylons. The competition was jointly administered by National Grid, the UK Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

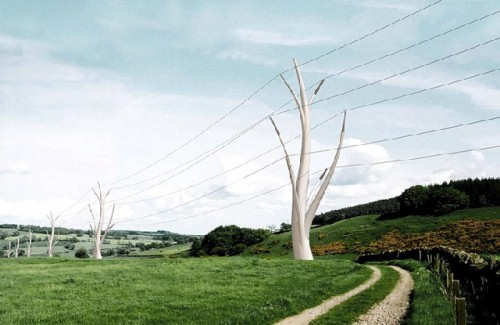

National Grid, one of the largest power providers in the United Kingdom and the northeastern United States held the competition to redesign its ubiquitous 84 year old electrified pylon (in the US, we call them "towers") that stretch across the English and Welsh countryside. Over 250 entries were received. Like most competitions, the submissions ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous.

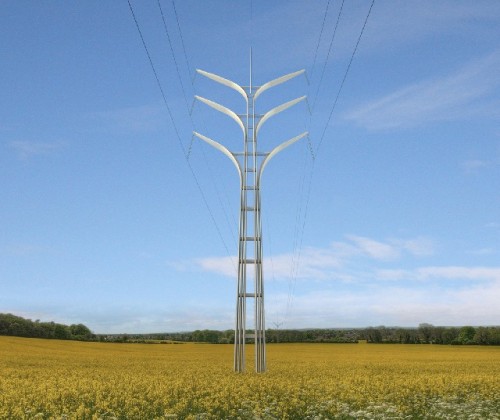

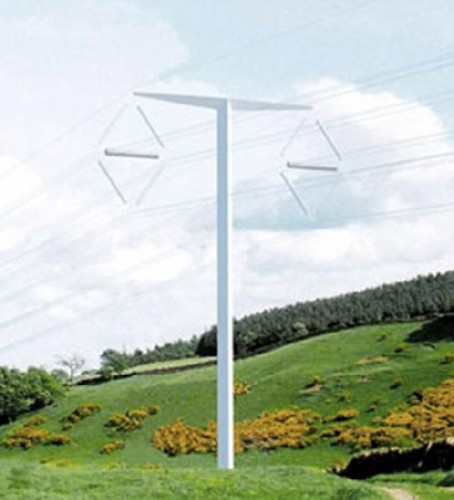

Bystrup's T-shaped design beat out five other shortlisted finalists in the contest to find a new form for pylons, which have been unchanged since the 1920s. The firm has designed a number of prototype pylons in the last decade or so. Their aim, as firm founder Erik Bystrup has said, is to "turn eyesores into art."

The Pylon Design competition was opened in late May, and the winner was announced in mid-October 2011. Out of 250 entries, six finalists were unveiled in September at an exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Like many, the call for entries to this competition read like a bit of a crapshoot, and it was.

The competition call for entries asked for ideas only and with no commitment beyond the competition to develop any of the schemes. However, in the event that the winning scheme is actually built, then the designers would be fully involved in the design development process (even compensated?) as well as actually credited. Entrants invited to stage two, the finals, were expected to further explore the technical viability (practicality) of their proposals.

Apparently, the elegant and spare T-Pylon design by Bystrup was unanimously agreed upon as the winner by the judges' panel. The firm will receive £5,000 ($7,846 US) in first prize money, while the five other finalists will receive £1,000 ($1,570 US). Not much for such an important effort. Ten times that amount would have been rather light considering the eventual impact of the design.

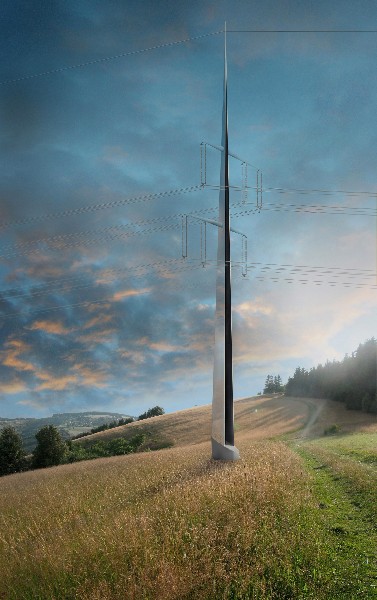

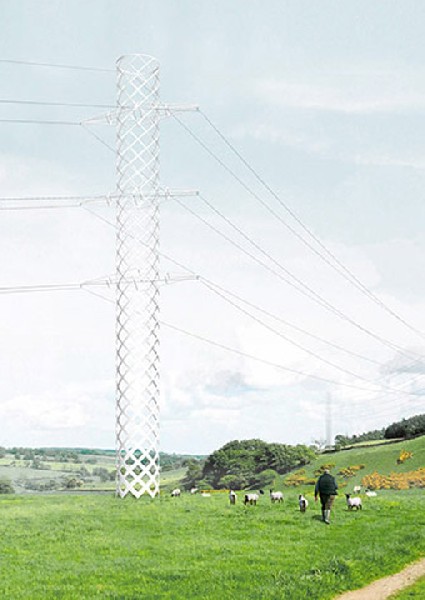

As a result of this contest, National Grid will now work with Bystrup to implement the T-Pylon design further. National Grid also wants to work with London-based runners-up Ian Ritchie Associates on their Silhouette entry and New Town Studio’s Totem submission. The first phase will be to develop a working model of the pylons.

How long the replacement of the nearly 25,000 existing electrical towers will take is anyone's guess considering National Grid's glacial approach to upgrading existing underground wire systems. Thinking of brown-outs and black-outs punctuating winters and summers in large US cities like Boston; not in the near future.

By the way, with corporate Greenspeak spouting from its website, why is so much wire running above ground that necessitates towers or pylons?

This question is not really addressed. The answer is found in the greater cost to be Green. Utility giants are not known for their liberal spending even on environmental issues. Things are done slowly with quite long range sustainable goals. The better to make stockholders happy.

Does anyone actually like a utility company? They don't seem to really care much.

If built, the T-Pylon will be two-thirds the height and weight of existing 50 meter tall, 30 ton grid towers dating from the late 1920s. So, the Bystrup design can be a real improvement on existing towers. Or will it become just a design footnote? Time and National Grid will tell.

Anyway, the quite public and showy competition underscores National Grid's brand and committment to a better environment. Visually the new pylons will add a more 21st Century appearance to the landscape--in the same white structure family of the huge wind turbines dotting the landscape all over Europe and now in parts of the US.

Only in the creative professions of architecture, landscape architecture, structural engineering and the various design specialties (urban, industrial, graphic, interior, etc,) are individuals and firms expected to demonstrate professional services and brilliant thinking for free. This is true of artists who enter some public art competitions as well.

In many ways, this is not quite right. But, and a big but, there have been some great results stemming from competitions.

No lawyers are asked to develop briefs or strategize major cases for no compensation. No doctor practices medicine or does medical/scientific research without being paid. Only in the design professions is free work expected.

The concept of the design competition gets creative juices flowing allowing institutions and corporations to get free work and pay a small fee for chosen entries.

In a down economy with less paid design work, this method has many adherents. The winning payoff is prestige and varying often paltry amounts of honorarium. In a some cases, the work is commissioned to be completed and then actually implemented. Other times the competition is about futuristic schemes, ideas and concepts.

Architecture and Design Competitions have been prevalent since the Acropolis in Athens. Invited competitions apparently were held for the design of medieval cathedrals as well. A 1419 competition was held to design the Florence Cathedral's dome. It was won by Flippo Brunelleschi. His winning entry resulted in a masterpiece of architectural form and beauty.

Open competitions were held since the late 18th century consistently in several countries including the United States, Great Britain and France. Literally hundreds of competitions were held during the 19th century. Notable were those that developed into New York's Central Park (1864) and London's Houses of Parliament (1835).

In the 20th Century, the Sydney Opera House (1955), Paris' Centre Georges Pompidou (1971), Berlin's Jewish Museum (1989) and London's Millennium Bridge (1996) have all brought significant additions to great cities. In the United States, Maya Lin's winning design for the Viet Nam Memorial Competition (1980) changed the concept of universal funeral homage.

However, all competitions do not turn out well. Winning first prize in a competition is not a guarantee that the project will be completed. A major case in point is the now highly homogenized decade long, angst evoking World Trade Center and Ground Zero redevelopment. Architect Daniel Liebeskind's competition-winning design has all but disappeared.

Usually but not always the jury for a competition is made up of outside or independent design professionals and stakeholders (government, institutional or community representatives). The whole competition process has many functions both overt and covert.

Competitions are often used to generate new ideas for the building, site or master plan design, to stimulate public debate, and to generate strategic publicity for the project. They allow emerging designers the opportunity to gain exposure, and established practitioners to add luster to their portfolio. They also build brand-awareness for the sponsor.

Denmark, Switzerland and Germany often use architecture competitions for public buildings, parks and projects. In France, design competitions are compulsory for all public buildings exceeding a certain cost. In the US, competitions are more hit or miss.

A forerunner of the Royal Institute of Architects, the Institute of British Architects, drafted a set of competition rules in 1839. Formal regulations were put in place in 1872. Also during the 19th Century, in the Netherlands, the Association for the Advancement of Architecture (Maatschappij tot Bevordering van de Bouwkunst) started developing conceptual competitions with the aim of stimulating architects' creativity.

And that's the point.

Architects, artists and designers of all types are not doctors or lawyers. They are not about procedure. Instead, they are about creativity. They are about enhancing the environment. Competitions allow this creativity to be channeled and sometimes even realized. The true value may be in the doing. Perhaps, this is worth the sacrifice?